Globalization, technology, productivity improvements, and the resulting restructuring of the world economy have led to fundamental changes that have destroyed the old paradigms of doing business. Whether these changes are on the whole good or bad, or who or what is responsible for bringing them into being, they simply are. Most cities, regions, and US states have extremely limited leverage in this marketplace and thus to a great extent are market takers more than market makers. They have to adapt to new realities, but a lack of willingness to face up to the truth, combined with geo-political conditions, mean this has seldom been done.

Three of those new realities are:

1. The primacy of metropolitan regions as economic units, and the associated requirement of minimum competitive scale. It is mostly major metropolitan areas, those with 1-1.5 million or more people, that have best adapted to the new economy. Outside of the sparsely populated Great Plains, smaller areas have tended to struggle unless they have a unique asset such as a major state university. Even the worst performing large metros like Detroit and Cleveland have a lot of economic strength and assets behind them (e.g., the Cleveland Clinic) while smaller places like Youngstown and Flint have also gotten pounded yet have far fewer reasons for optimism. Many new economy industries require more skills than the old. People with these skills are most attracted to bigger cities where there are dense labor markets and enough scale to support items ranging from a major airport to amenities that are needed to compete.

2. States are not singular economic units. This follows straightforwardly from the first point. As a mix of various sized urban and rural areas, regions of states have widely varying degrees of economic success and potential for the future. Their policy needs are radically different so the one size fit all nature of government rules make state policy a difficult instrument to get right. Additionally, many major metropolitan areas that are economic units cross state borders.

3. Many communities may never come back, and many laid-off workers may never be employed again. Realistically, many smaller post-industrial cities are unlikely to ever again by economically dynamic no matter what we do. And lost in the debate over the n-th extension of emergency unemployment benefits is the painful reality that for some workers, especially older workers laid off from manufacturing jobs, there’s no realistic prospect of employment at more than near minimum wage if that. As Richard Longworth put it in Caught in the Middle, “The dirty little secret of Midwest manufacturing is that many workers are high school dropouts, uneducated, some virtually illiterate. They could build refrigerators, sure. But they are totally unqualified for any job other than the ones they just lost.” This doesn’t even get to the big drug problems in many of these places. This isn’t everybody, but there are too many people who fall into that bucket.

I want to explore these truths and potential state policy responses using the case study of Indiana. An article in last week’s Indianapolis Business Journal sets the stage. Called “State lags city with science, tech jobs” it notes how metropolitan Indianapolis has been booming when it comes to so-called STEM jobs (Science, Technology, Engineering, Math). Its growth rate ranked 9th in the country in study of large metro areas. However, the rest of Indiana has lagged badly:

Indiana for more than a decade has blown away the national average when it comes to adding high-tech jobs. But outside the Indianapolis metro area, there isn’t much cause for celebration.

Careers in science, technology, engineering and math–typically referred to as STEM fields–have surged in growth compared to other careers in Marion and Hamilton counties. It’s a boon for economic development, considering the workers earn average wages almost twice as high as all others, and employers sorely need the skills. Dozens of initiatives focus on building STEM jobs in the state.

A recent report ranked the Indianapolis-Carmel metro area ninth in the country in STEM jobs growth since the tech bubble burst in 2001. But while the metro area has grown, the rest of Indiana has barely budged from the early 2000s, an IBJ analysis of U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics found.

Indianapolis grew its STEM job base by 39% since 2001 while the rest of the state grew by only 10% (only 6% if you exclude healthcare jobs). Much of the state actually lost STEM jobs.

This divergence between metropolitan Indianapolis (along with those smaller regions blessed with a unique asset like Bloomington (Indiana University), Lafayette (Purdue University) and Columbus (Cummins Engine)) and the rest of the state is a well-worn story by now. Here are a few baseline statistics that tell the tale.

| Item | Metro Indianapolis | Rest of Indiana |

| Population Growth (2000-2012) | 15.9% | 4.1% |

| Job Growth (2000-2012) | 5.9% | -7.2% |

| GDP Per Capita (2012) | $50,981 | $34,076 |

| College Degree Attainment (2012) | 32.1% | 20.1% |

“Indianapolis is somewhat of a sponge city for the whole region,” said Mark Schill, vice president of research at Praxis Strategy Group, an economic development consultant in North Dakota.

The situation in Indiana, Schill said, is common throughout the United States: States with one large city typically see their engineers, scientists and other high-tech workers flock to the urban areas from smaller towns.

Even I find it very surprising that of my high school classmates with college degrees, half of them live in Indianapolis – this from a tiny rural school along the Ohio River in far Southern Indiana near Louisville, KY.

What has Indiana’s policy response been to this to date? I would suggest that the response has been to a) adjust statewide policy levers to do everything possible to reflate the economy of the “rest of Indiana” while b) making subtle tweaks attempt to rebalance economic growth away from Indianapolis.

On the statewide policy levers, the state government has moved to imposed a one size fits all, least common denominator approach to services. The state centralized many functions in a recent tax reform. It also has aggressively downsized government, which now has the fewest employees since the 1970s. Tax caps, a comparative lack of home rule powers, and an aggressive state Department of Local Government Finance have combined to severely curtail local spending as well. Gov. Pence took office seeking to cut the state’s income tax rate by 10% (he got 5%), and now wants to eliminate the personal property tax on business. Indiana also passed right to work legislation.

I call this “the best house on a bad block strategy.” I think Mitch Daniels looked around at Illinois, Ohio, and Michigan and said, “I know how to beat these guys.” Indiana is not as business friendly as places like Texas or Tennessee, but the idea was to position itself to capture a disproportionate share of inbound Midwest investment by being the cheapest. (I’ll get to Pence later).

The subtle tweaks have been income redistribution from metro Indianapolis (documented by the Indiana Fiscal Policy Institute) and using the above techniques and others to apply the brakes to efforts by metro Indy to further improve its quality of life advantage over many other parts of the state (see my column in Governing magazine for more). One obvious example is a recent move by the Indiana University School of Medicine to build full four year regional medical school campuses and residency programs around the state with the explicit aim of keeping students local instead of having them come to Indianapolis for medical training.

What there’s been next to nothing of is any sense of metropolitan level or even regional thinking. The state does administer programs on a regional level, but the strategy is not regionally oriented and the administrative borders don’t even line up. Here are the boundaries of the various workforce development boards:

Add it all up and it appears that Indiana has decided to fight against all three new realities above rather than adapting to them. It rejects metro-centricity, imposes a uniform policy set, and is oriented towards trying to reflate the most struggling communities. I don’t think this was necessarily a conscious decision, but ultimately that’s what it amounts to.

When you fight the tape, you shouldn’t expect great results and clearly they haven’t been stellar. Since 2000, Indiana comfortably outperformed perennial losers Michigan and Ohio on job growth (well, less job declines), but trailed Kentucky, Wisconsin, Minnesota, Iowa, and Missouri. But notably, Indiana only outpaced Illinois by a couple percentage points. That’s a state with higher income taxes (and that actually raised them) that’s nearly bankrupt and where the previous two governors ended up in prison. Yet Indiana’s job performance is very similar. What’s more, Hoosier per capita incomes have been in free fall versus the national average, likely because it has only become more attractive to low wage employers.

Fiscal discipline, low taxes, and business friendly regulations are important. But they aren’t the only pages in the book. Workforce quality counts for a lot, and this has been Indiana’s Achilles heel. (My dad, who used to run an Indiana stone quarry, had trouble finding workers with a high school diploma who could pass a drug test and would show up on time every day – hardly tough requirements one would think). Also aligning with, not against market forces is key.

I will sketch out a somewhat different approach. Firstly, regarding the chronically unemployed, clearly they cannot be written off or ignored. However, I see this as largely a federal issue. We need to come to terms with the reality that America now has a population of some million who will have extreme difficulty finding employment in the new economy (see: latest jobs report). We’ve shifted about two million into disability rolls, but clearly we’ve to date mostly been pretending that things are going to re-normalize.

For Indiana, the temptation can be to reorient the entire economy to attract ultra low-wage employers, then cut benefits so that people are forced to take the jobs. I’ve personally heard Indiana businessmen bemoaning the state’s unemployment benefits that mean workers won’t take the jobs their company has open – jobs paying $9/hr. Possibly the 250,000 or so chronically unemployed Hoosiers may be technically put back to work through such a scheme – eventually. But it would come at the cost of impoverishing the entire state. Creating a state of $9/hr jobs is not making a home for human flourishing, it’s building a plantation.

Instead of creating a subsistence economy, the focus should instead be on creating the best wage economy possible, one that offers upward mobility, for the most people possible, and using redistribution for the chronically unemployed. You may say this is welfare – and you’re right. But I would submit to you that the state is already in effect a gigantic welfare engine. In addition to direct benefits, the taxation and education systems are redistributionist, and the state’s entire economic policy, transport policy, etc. are targeted at left-behind areas (i.e., welfare). Even corrections is in a sense warehousing the mostly poor at ruinous expense. So Indiana is already a massive welfare state; we are just arguing about what the best form is. I think sending checks is much better than distorting the entire economy in order to employ a small minority at $9/hr jobs – but that’s just me. Again, we are in uncharted territory as a country and this is ultimately going to require a national response, even if it’s just swelling the disability rolls even more. I do believe people deserve the dignity of a job, but we have to deal with the unfortunate realities of our new world order.

With that in mind, the right strategy would be metro-centric, focusing on building on the competitively advantaged areas of the state – what Drew Klacik has called place-based cluster – and competitively advantaged middle class or better paying industries.

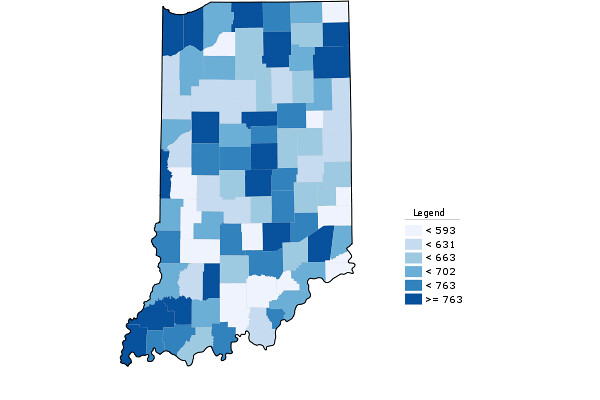

Contrary to some of the stats above, this is not purely an Indianapolis story. Indiana has a number of areas that are well-positioned to compete. Here’s a map with key metro regions highlighted:

Additionally, three other large, competitively advantaged metro areas take in Indiana territory: Chicago, Cincinnati, and Louisville. These are all, like Indy, places with the scale and talent concentrations to win. True, none of the Indiana counties that are part of those metros is in the favored quarter. But they still have plenty of opportunities. I’ve written about Northwest Indiana before, for example, which should do well if it gets its act together.

This covers a broad swath of the state from the Northwest to the Southeast. It comes as no surprise to me that Honda chose to locate its plant half way between Indianapolis and Cincinnati, for example.

The state should align its resources, policies, and investments to enable these metro regions to thrive. This doesn’t mean jacking up tax rates. Indiana should retain its competitively advantaged tax structure. But it should mean no further erosion in Indiana’s already parsimonious services. The state is already well-positioned fiscally, and in a situation with diminishing marginal returns to further contraction.

Next, empower localities and regions to better themselves in accordance with their own strategies. This means an end to one size fits all, least common denominator thinking. These regions need to be let out from under the thumb of the General Assembly. That means more, not less flexibility for localities. Places like Indianapolis, Bloomington, and Lafayette would dearly love to undertake further self-improvement initiatives, but the state thinks that’s a bad idea. (I believe this is part of the subtle re-balancing attempt I mentioned).

It also means using the state’s power to encourage metro and extended region thinking. For example, last year within a few months of each other the mayors of Indianapolis, Anderson, and Muncie all made overseas trade trips – separately and to different places. That’s nuts. The state should be encouraging them to do more joint development.

This also means recognizing the symbiotic relationship that exists between the core and periphery in the extended Central Indiana region, clearly the state’s most important. The outlying smaller cities, towns, and rural areas watch Indianapolis TV stations, largely cheer for its sports teams, get taken to its hospitals for trauma or specialist care, fly out of its airport, etc. Metro Indianapolis and its leadership have also basically created and funded much of the state’s economic development efforts (e.g., Biocrossroads) and many community development initiatives (the Lilly Endowment). Many statewide organizations are in effect Indianapolis ones that do double duty in serving the state. For example, the Indiana Historical Society. (There is no Indianapolis Historical Society).

On the other side of the equation, Indianapolis would not have the Colts and a lot of other things without the heft added from the outer rings out counties that are customers for these amenities. It benefits massively from that, particularly since it’s a marginal scale city. One of the biggest differences between Indy and Louisville is that Indy was fortunate enough to have a highly populated ring of counties within an hour’s drive.

So in addition to aligning economic development strategies around metros, and freeing localities to pursue differentiated strategies, the state should encourage the next ring or two of counties that are in the sphere of influence of major metros to align with their nearest larger neighbor.

Contrary to popular belief, this is a win-win. When I was in Warsaw, Indiana, people were concerned that many highly paid employees of the local orthopedics companies lived in Ft. Wayne. From a local perspective, that’s understandable and obviously they want to be competitive for that talent and should be all means go for it. On the other hand, what if Ft. Wayne wasn’t there for those people to live in? Would those orthopedics companies be able to recruit the talent they need to stay located in small town Indiana?

It’s similar for other places. Michael Hicks, and economist at Ball State in Muncie, said, “Almost all our local economic policies target business investment and masquerade as job creation efforts. We abate taxes, apply TIFs and woo businesses all over the state, but then the employees who receive middle-class wages (say $18 an hour or more) choose the nicest place to live within a 40-mile radius. So, we bring a nice factory to Muncie, and the employees all commute from Noblesville.” Maybe Muncie isn’t completely happy about this, understandably. But would they have been able to recruit those plants at all (and the associated taxes they pay and the jobs for anybody who does stay local) if higher paid workers didn’t have the option to live in suburban Noblesville? Would the labor force be there?

I saw a similar dynamic in Columbus. Younger workers recruited by Cummins Engine chose to live in Greenwood (near south suburban Indy). Columbus wants to keep upgrading itself to be more attractive – a good idea. But the ability to reverse commute from Indy is an advantage for them.

Louisville, Kentucky has one of the highest rates of exurban commuting the country because so many Hoosiers in rural communities drive in for good paying work.

This is the sort of thinking and planning that needs to be going on. Realistically, most of these small industrial cities and rural areas are not positioned to go it alone and they shouldn’t be supported by the state in attempting to do so. They need to a align with a winning team.

There are two groups of places that require special attention. One is the mid-sized metro regions of Ft. Wayne, Evansville, and South Bend-Elkhart. These places are too far from larger metros and aren’t large enough themselves to have fully competitive economies. No surprise two of the three lost STEM jobs. Evansville has done better recently on the backs of Toyota, but has a vast rural hinterland it cannot carry with its small size. The region has done ok of late, but it has also received gigantic subsidies in the form of multiple massive highway investments, and now a massive coal gasification plant subsidy. I don’t believe this is sustainable. These places need special assistance from the state to devise and implement strategies.

The other grouping consists of rural and small industrial areas that are too far outside the orbit of a major metro to effectively align with it. This would includes places like Richmond or Blackford County. They might get lucky and land a major plant, but realistically they are going to require state aid for some time to maintain critical services.

For the last two groups especially, there also needs to be a commitment by the state’s top brain hubs – Indy and the two university towns – to applying their intellectual and other resources to the difficult problem at hand. Part of that involves helping them be the best place of their genre that they can. While cities are competitively advantaged today, not everybody wants to live in one. So there is still an addressable market, if not as large, for other places.

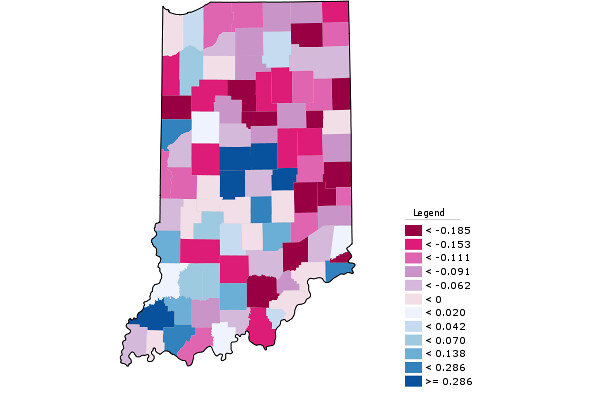

Put it together and here’s the map that needs to be changed. It’s percentage change in jobs, 2000-2012:

– Retain lean fiscal structure but limit further contractions

– Goal is to build middle class or better economy, not bottom feeding

– Align economic development efforts to metro areas, particularly larger, competitively advantages locations. Align capital investment in this direction as well.

– Greater local autonomy to pursue differentiated strategies for the variegated areas of the state

– Special attention/help to strategically disadvantaged communities, but not entire state policy directed to servicing their needs.

– Utilization of transfers for the chronically unemployed pending a federal answer, but again, not redirection of state policy to attract $9/hr jobs.

This requires a lot of fleshing out to be sure, but I think is broadly the direction.

Back to Gov. Mike Pence, would he be on board with this? He’s Tea Party friendly to be sure and interested in fiscal contraction. But he’s not a one-trick pony. He’s actually taken some interesting steps in this regard. He is subsidizing non-stop flights from Indianapolis to San Francisco for the benefit of the local tech community. He also wants to establish another life sciences research institute in Indy. And he’s talked about more regionally focused economic development efforts. It’s a welcome start. I think he groks the situation more than people might credit him for. Keep in mind that he did not establish the state’s current approach, which arguably even pre-dated Mitch Daniels, and he has to deal with political realities. And if as they say only Nixon could go to China, then although a reorienting of strategy is not about writing big checks, still perhaps only someone with conservative bona fides like Pence can push the state towards a metro-centric rethink.

Are metros that clearly dominate their states at an advantage? Columbus has to compete with two other metros, while Indy stands alone in Indiana.

Well Arenn I agree somewhat but I think we are seeing a change in attitude in Indianapolis.

Recently all the economic development arms of Indianapolis consolidated into the Indy chamber of commerce. Isnt that a step in the right direction?

Also I should add I think were starting to see a turn around in Indiana in regards to people relocating from around the country to take the job openings here.

That also could be a side effect of this economy. as the old saying goes (People move where the jobs are)

I would ideally like to see the 5 major metro areas of Indiana: Indianapolis, Fort Wayne, Especially Northwest Indiana, Evansville and South Bend/Elkhart create their own regional economic development agencies to bring jobs to the whole region.

So what’s going to happen to this disenfranchised demographic sector whose manufacturing jobs succumbed to outsourced in the Far East, the ones who will never regain their former economic status and disposable income?

It’s easy to say reeducation or retraining, but in one’s 40s to 60s that is a daunting consideration to transition into an entirely new and different career while attempting to sustain the nuts and bolts of daily life. The prosperous option is high-tech geared but most may not be aptitude qualified for the quest, nor have the funds to finance such a career makeover, nor have the fortitude to pursue such an endeavor in their declining years.

Since most of the job creations are in technologies and this sector is mushrooming in the metros, which will push out the disenfranchised to where? To new ghettos and tent cities on the extremity of the sparkling metros? This has actually happened in Silicon Valley (San Jose), the rich high-tech capital of the world has a shameful reality; the contrast is demonstratively severe, and it boasts the largest homeless camp in America called “The Jungle”. Is this a trend that now awaits others Metros?

Unfortunately, under the current federal death-wish economic policies the Middle Class (which was once the backbone that built this nation) is eroding, and a glaring dichotomy between Haves and Have-Nots is gaining steam with death to Middle.

“This Map Of Homelessness In Silicon Valley Shows Just How Close The Tech Elite Are To The Destitute”

http://www.businessinsider.com/homeless-in-silicon-valley-infographic-2013-8?op=1

“Video: The Homeless Tent City in Google and Facebook’s Backyard”

http://www.motherjones.com/mojo/2013/04/video-homeless-tent-cities-silicon-valleys-backyard

“Silicon Valley adds tech jobs, homeless”

http://www.foxnews.com/tech/2013/03/11/silicon-valley-adds-tech-jobs-homeless/

Additionally, yes indeed, I concur, “metrocenticism” is more laser-focused, ideal and closer to the local problems that obviously require adroit strategic solutions. The convoluted diluted strategies of the State and the debilitating micromanagement of the Feds gravely hamper and escalate adverse effects, as the San Jose case in point clearly demonstrates.

@Matthew Hall, I don’t think it’s necessarily about having a single dominant metro. Nashville is outperforming Indianapolis, but has to compete with Memphis for state attention. I happen to think the multiple large metros of Ohio are a source of advantage to the state. One challenge I do see is that there are a number of fairly large metro regions in Ohio that don’t quite have the heft to take off on their own. Dayton and Youngstown for example. They can align to their nearest neighbors, but are so large themselves that it would take a long time for there to be an impact.

@Jon Seisa, my point is basically that many of these people will never work again. Few politicians will come out and say that, but you here it whispered around and a few commentators are willing to give the raw reality.

The left-leaning Economic Policy Institute just put out a report that says that if you use the labor force participation rate at the officially declared end of the recession and projected it forward, the unemployment rate actually hasn’t gone down at all since 2009. The reductions are entirely due to people dropping out of the labor force.

We are 7.9 million jobs short of where we need to be to renormalize the labor market. That doesn’t even fully account for the fact that many of the jobs we have created are part time or low paying. We only added 75,000 jobs total last month. We need to be averaging way more than 200,000 jobs a month growth to even start putting a dent in that. Even in the best case scenario we are talking 2+ years, but likely much longer.

I don’t profess to have a ready answer but we as a country have to start having the difficult conversation about this, not just doing rolling temporary extensions of unemployment benefits and relaxing disability standards while we pretend things will be back to the way they were before if the economy would just pick up a bit.

The Wall Street Journal just did a story on labor-force dropouts. Most seem to be baby-boomers, so this is a problem that demographics may be solving.

The keys will be how the jobs economy absorbs the Millennial generation, who are now 14-32, and whether those young folks’ spending patterns will produce a demand boom for housing and goods. I’d suggest that it’s currently reflected in the building boom and occupancy rates for apartments in Indy.

Those young men and women largely fought our two most recent wars, and the veterans have GI Bill benefits and VA loan potential. The peak of the generation is now just post-college age (peak birth years 1988-90) and it is the generation with the highest (amazingly high) college-completion rate. And they are a “metropolitan” generation.

This is of particular importance to Indiana, typically one of the top 3-5 states for military volunteers (on a percentage of population basis). We need to get it right.

The same thing has happened in Oregon as has happened in Indiana: the metro area has grown while the outlying economy has shrunk.

Portland is the manufacturing, design, and commercial capital of the area, the same as it’s been for the last 150 years. It used to be surrounded by a constellation of mill towns cutting timber from the nearby forests. That timber is gone, so those towns are trying to remake themselves as tourist centers, a struggle for many. The state has subsidized highways to and through them. Any bright young person growing up in them will likely leave for a job in the city. Otherwise they’ll be working at the local convenience store or commuting long distances to a service job in the regional center, which is probably kept in business by the number of retirees in the area. As that retiree population dies off, even the regional centers will will lose their business.

The solution is better education. For at least the next 20 or 30 years, we can’t bring good jobs back to the small towns, but we can give the kids growing up in those places the education they need to get a good job in the city. And if there are enough of them there, the companies with good jobs will come or, ideally, be created locally.

Unfortunately, not only do the schools aim low, but what they teach lacks application. Most high schools teach architectural drafting. How many teach 3D drafting of parts, and then make those parts on 3D printers? How many schools really teach robotics, and give kids the good basis in logic necessary to program? Beyond the STEM courses, there’s a basic question of rigor in critical thinking, writing and speaking.

As an economic strategy, it is very hard to be the lowest cost producer. Far better to be the quality leader in a niche. Indianapolis is the sports capital of the U.S. With all the focus on food, nutrition and fitness, there’s more than enough there to be a leading sector. An education curriculum that includes health and training would prepare a lot of students for jobs in this area.

Matt Yglesias had a short piece about one aspect of the current welfare system and how it likely leads to people becoming mired in places with no hope for recovery.

http://www.slate.com/blogs/moneybox/2014/01/10/snap_should_be_cash_instead.html

P.S. The above comment should have read, “Indianapolis is the amateur sports capital of the U.S.” Is it not also a leader in motor sports? The auto factories may be gone, but how about new ventures in personal mobility, especially for retirees?

Rod, the auto assembly and major components factories aren’t gone from Indiana, just Indianapolis itself. As Aaron points out, the Honda factory in Greensburg is about 35-40 minutes from the southeastern quarter of Indianapolis. Subaru is 40-45 minutes from the northwest part of Indianapolis. Chrysler’s state-of-the-art Kokomo Transmission operation is 35 minutes from the northern suburbs.

Indianapolis is barely an hour from the state’s eastern and western borders. Its long-range commute distance takes in a big chunk of the state. The well-educated and well-paid engineering, technical, and management folks in those factories I cited are likely to live in Indianapolis or its suburbs and commute to those factories or others. I did that twice in the 1980s while working for auto-parts manufacturers in small cities within Indy’s one-hour drive radius; I am living proof that the Michael Hicks comment Aaron highlighted was applicable even 30 years ago.

Chris,

Is the de facto strategy for these auto makers to locate as satellites to the larger cities, enjoying the low costs of land and all the freebies that come with eager small cities?

Your most interesting comment is your last. Does this mean that the top engineering talent is locating in the center of this solar system of planets? I would think there would be a temptation to live farther out, but given the need for job mobility, you’d want to be located closer in.

Rod

Another factor is that several of these foreign auto makers also want to avoid hiring union-legacy (e.g. former employees of the Indianapolis’ old Chrysler plant) or union-sympathetic employees who reside closer in. Honda only allowed hires from 20 counties in IN for its Greensburg plant. Some say its a proxy for racial discrimination.

http://www.democraticunderground.com/discuss/duboard.php?az=view_all&address=367×4175

urbanleftbehind: “Some people” are making a nice straw man argument.

Marion County (Indianapolis) was one of the counties included in the Greensburg hire radius. Marion County is only 65% non-Hispanic Caucasian, lower than the US average. I think including it was a way to avoid the appearance of racial discrimination.

And a big chunk of the now-gone UAW jobs in Marion County were in my neighborhood, on the east and southeast sides (Chrysler electrical plant, Ford, and Harvester), so including Marion and its east/southeast suburbs would have made those union folks eligible at Honda.

Toyota is right up the road from Evansville, a city with a strong (Whirlpool) union-factory history. Subaru is in Lafayette, where the other major manufacturers are Alcoa and Cat, big legacy union companies.

—

Rod: it’s about a 40-50 minute drive across the Indy metro from one exurban fringe to the other, via the Interstates. So if a worker is willing to accept that commute from a given quarter of the city, his/her work options are maximized with metro and outstate opportunities. Even if s/he wanted to change jobs to an outstate company on the opposite side of the city, it’s a far less-wrenching change to move from one part of a familiar metro to another.

30 years ago it took me 50-55 minutes to get to the far side of Columbus from the north-central part of Indianapolis proper. This is germane today because at the time, I lived just a few blocks from where the current Cummins CEO now lives.

*so including Marion County

Rod, I didn’t answer: yes, green-field sites are the ones typically chosen for these big new factories in Indiana.

–Subaru’s site is along I-65 south of Lafayette.

–Nestle built on the outskirts of Anderson along I-69.

–Chrysler’s new transmission plant is on US31, at a former cornfield crossroads between Kokomo and Westfield (a 3rd-ring Indy suburb).

–GM’s big pickup truck (Chevy Silverado/GMC Sierra) plant is on the southwestern corner of the Fort Wayne metro where I-469/US24 meets I-69.

–I-74 was built with a looping bend around Greensburg, and Honda is there on the interstate at the edge of town…almost exactly halfway between Indianapolis and Cincinnati, as Aaron points out. (At the time, Cincinnati was a Delta hub and probably offered better air service to Japan, but Indy was better for finding experienced auto-industry people)

–Toyota is on US41 in Princeton, 30 miles north of Evansville.

Chris…that makes four major companies. What is the region doing to build up small companies with related expertise?

Shouldn’t ‘geographic discrimination’ be illegal much as redlining?

Rod, there really wasn’t/isn’t a need. Indiana has long been one of the two or three leading states for both manufacturing generally (as a share of the state’s jobs) and has 100 years of experience as an auto-parts source; there is still a good bit of human capital in the higher-skill fields.

Japan-based car companies came to Indiana in part because the component expertise already existed here. Their first-tier suppliers followed them, and there were active efforts to recruit the Japan-based suppliers’ plants, especially in and around Columbus IN. Those companies hired Hoosiers displaced (or lured) from Detroit Three component plants and suppliers. (I was one of those hires.)

Interestingly, some of those companies were in parts lines not immune to globalization in the 90s and several succumbed to competition from lower-wage Asian factories. It’s the high-value-add and high-shipping-cost pieces and parts made in the US now: drive shafts (NTN Columbus), transmission castings (Ryobi Shelbyville), wheels (Enkei Columbus).

Matthew, you might have it backward. IIRC, Indiana negotiated with Honda to hire from specific Indiana counties rather than relocating a bunch of people from their existing assembly plants in Ohio. It was one of the conditions of the state infrastructure and tax incentives. The reality is that the 20 counties are probably just those within reasonable commuting distance anyway.

@ Aaron – This unemployment data is quite perplexing and yet frightening as it portents unknown dark horizons. Perhaps a new emergent form of ‘gentrification’ is emerging in the metros having the unfortunate consequences on the new disenfranchised group affected, precipitated inadvertently by the dynamics of high-tech globalism’s paradigm shift. For every cause there’s an affect and ramifications, unforeseen, some pleasant surprises, some not so, despite how noble the initial mobilizing endeavor may be.

> my point is basically that many of these people will never work again.

If that is the coming reality then so is 9$/hr jobs. Expecting decent welfare in a low-tax environment seems an even worse option.

Just reading Travels of a T-Shirt in the Global Economy. China has lost more textile jobs in last 10 years than the US. It’s not that they are moving, but being automated out of existence.

I am a STEM graduate currently in a non-STEM job so I could live in my hometown of Evansville. There are a few STEM jobs in Evansville, but they are occupied by other people. I did work in Indianapolis for over 10 years in mostly STEM, but when I wanted to move back to Evansville to be closer to my family, I had to take a non-STEM job.

As for continued education in STEM for myself, I have not been able to work STEM classes into my schedule, such as I wanted to update my technical graphics and CAD skills, but there are so few classes offered, and not flexible.

I am happy in my currently employment, but I do think the STEM shortage is somewhat of manufactured myth overall.

I see a great future for agriculture and related products/services. Just looking at the google map, Indiana seems to still be in Ag in a big way. Even at very short distances form Indy. Farms seem to be a little smallish – but i know almost nothing about farming. I recently drove through South Alabama and could see idle acreage being cleaned to put back into production.

I haven’t given much thought to how a relationship between Indy and its satellite rural region (which I think it should be thought of liberally as Mr. Renn drew his circles in the article). I think there is a big win-win situation here.

wkg, Indy is already home to two ag-related life sciences companies: Dow Agrosciences (ag-chem) and Elanco Animal Health, as well as the national FFA (Future Farmers of America) HQ. Purdue, the state’s “aggie” and vet school, is just an hour northwest. Until a decade or two ago, the big AM radio station in Indy had a farm reporter and daily or weekly farm reports.

A current Verizon commercial shows a farmer installing WiFi/cellular field sensors. Before that, there was a run of “laser leveling” fields so that water runoff would be controlled and topsoil loss would be minimized. High tech applied to fieldwork and food production.

Aaron, could you weigh in on a “back to the future” ec dev strategy for Central Indiana? Cars and corn? It seems a bit counterintuitive to me, but the ec dev world is abuzz with “advanced manufacturing” (cars) and “life sciences” (corn, cows, and hogs, not to mention pharma). These are not pipe dreams in Indiana…we already have a good base. You always suggest building from strength, and a couple of smart people who post here seem to lean that way.

Chris: I did an ED strategy on this for UC Davis two years ago. Contact me offline at rodstevens@seanet.com. big potential.

Chris: thanks for the info.

The meds with regard to people is getting to be rather crowed field. I never thought of meds for animals. I think your onto something.

I had the same thought at Matthew Hall in the 1st comment. Really Columbus should be killing Indianapolis. It should be the Austin of the Midwest. It has virtually everything Austin has, except maybe the reputation. A massive research university, several other major tech players, and it was home to the first internet service provider(CompuServe) which could have been our Dell (maybe luck played a role too).

However, I don’t know but I bet Indianapolis’ STEM growth has been higher than Columbus’. Some of the may be cultural. However, I wonder if much of it isn’t due to the presence of other large metros. Indianapolis, and Nashville, have enough “clear space” to vacuum up just about every STEM worker in the surrounding area. Plus Indianapolis has the advantage of being the only large metro in the State. Columbus, at least psychologically, and somewhat physically, has to compete more.

One good example-the Cleveland Clinic, which is Ohio’s premiere hospital and private research institution, directly competes with Ohio State, the largest public research institution, for grants, talent and general reputation. I imagine much more talent and interest turning towards OSU if the Cleveland Clinic weren’t around.

Second example-Cincinnati Children’s. Nationwide Children’s in Columbus recently went on an expansion binge, but it’s still far behind Cincinnati in terms of reputation (Cincinnati’s ranked 3rd best in the nation children’s hospital by US News & World Report in 2011). In fact, several years ago, Ohio State made a deal with Cincinnati Children’s on a major research initiative. Now there were some turf battle issues there too, but if Cincinnati Children’s wasn’t available, I doubt OSU would have gone to Riley Hospital in Indianapolis, for example. The outcry would have been much greater from the legislature to partner with an out-of-state hospital.

A final example is flight availability. Columbus is very well located to be an air hub. In fact, there are probably few cities in America that are better located to be a central hub between several highly-populated areas. However, the fact that several cities are so close and most have bigger, more well-established airports with better service is very harmful to Columbus. I really think that a relative lack of air service has really hurt the City. And since there are several other metros with airports in the State, I don’t see our Governor subsidizing flights to San Francisco, which Columbus could desperately use, because then he would have to do it for every other city, too.

Now on a state-wide level, having this many strong institutions is great-it means Ohio has a substantial number of strong assets upon which to build. But on a metro level, it creates a lot of competition, and if Ohio’s metros are beating each other up, we’re all a little weaker for it. It’s not like being in New York City, where one great hospital loses out to another down the street. It’s different metros. So while Columbus has clearly been the success story of Ohio, one has to wonder if it wouldn’t be doing even better with a little more space.

A friend of mine used to run a consulting firm that worked with brain-drain cities with strong universities. He said, over and over, that Columbus should be one of the Midwest’s winner cities over the next 20 years.

These institutions should work together. Here in the Seattle area, the University of Washington has outgrown its campus, and has moved, along with the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center, into a new tech area of the city known as “South Lake Union”. That, combined with the Gates Foundation and its focus on world health issues, has created an incredibly strong health center there. There are a number of biotech companies as well as private, non-profit biotech research institutes, and, combined with the Gates Foundation efforts, it is becoming one of the world centers in health policy.

I understand the institutional imperative to grow and feed the research machine. I also believe, however, that it is dangerous for places to be dominated by just a few institutions. (We used to call those places “company towns”). Places like this tend to become undemocratic in how they make decisions, since they usually differ to the opinions of the big employers. This discourages the up-and-comers, the leaders of the future who need something different, who will gently change the status quo over time. I don’t know how you do it, but you have to give these young firms room to breath, or, inevitably, they will de-camp to the big city, if only to tap a larger management pool.

@George, I looked up the STEM study. Columbus wasn’t included in the rankings because of some data classification anomalies. However, it generally ranks quite high in various tech rankings.

I don’t think Columbus has much to be ashamed of. It’s doing well and is positioned to be the #1 or #2 Midwest metro in economic and demographic performance this decade (depending on how MSP does).

I agree the potential is very high but there’s something I can’t quite put my finger on about Columbus. It’s related to my observation that Columbus checks all the boxes but seldom innovates or sets the agenda. I think that’s a symptom of something.

Aaron:

I agree. That’s kind of what I was saying. This is a great city in many ways, but should be performing even better. It’s kind of like looking at a basketball player that’s scoring 20 pts and getting 10 rebounds a game, and saying, “Man he SHOULD be getting 30 pts and 20 rebounds a game.”

In the past there was very little organization around economic development and pushing innovation, but that has changed drastically in the past 10 years. I would say Columbus now has a very well-organized economic development strategy. I hope that in the next 10 years this raises Columbus to the level it should be on.

One thing I forgot to mention in your analogy though, George. Austin has to compete with two well-established and much larger metros in the state of Texas. Houston and DFW are much tougher competition to Austin than Cleveland and Cincy are to Columbus. So Austin overcame some of the same structural issues facing Columbus.

Aaron, compared to Austin, Columbus doesn’t have SXSW, and that’s huge. That is something major-league in the pop-culture realm, even if they want to think it’s countercultural. Plus Austin became a tech hub in the 60s/70s with IBM and SEMI there. Non-trivial from a STEM point of view.

I think what’s missing about Columbus is a “major league” vibe. The city just isn’t known widely for any one thing.

SXSW wasn’t even founded until 1987, though admittedly music has been big there for a while.

For everything Austin has that Columbus doesn’t, you can post to the opposite: Battelle Memorial Institute, a major medical school, a former super-regional banking giant (JPM still employs around 15,000 there), and more.

I maintain the differences are likely cultural and life cycle related. I love to use the example of Indy and Nashville. Arguably equivalent cities a la CBUS and Austin, but Nashville has turned it on. Sunbelt? Yes, but a growth story of more recent vintage. I’ve spent quite a bot of time there and they just have a different ambition level and a different vibe. There are key places I haven’t been like Austin, Portland (yes, believe it or not!) and Salt Lake City, but of the places I’ve visited, Nashville is my favorite small city. And not because of any particular unreplicable asset they have.

Something made Austin and Nashville better greenfields than Columbus and Indy.

Austin’s explosive growth has been pretty unceasing across the years. An average January high temperature of 61, Texas’ leading position in the oil and gas industry and the unceasing flow of tax revenue therefrom, the University of Texas, SEMI, SXSW…all these things build on one another. The city has leading positions in more than one thing, plus it’s an eds/meds/capital city.

The same is true of Nashville: average January high of 47, eds/meds(Vanderbilt)/capital city, leading position in country music and entertainment.

My point in #33 above: you detected something “missing” which you assert is vibe or feel. I say it is something very tangible in each case. Nashville and Austin both outgrow Indy and CBUS because of these modern tangible assets.

And as always, I add, never overlook a beneficial (weather) climate, mountains, or beaches…places people want to be in a macro sense. Nashville is six hours and Austin three from the Gulf Coast. Austin is close to Texas’ Hill Country. Nashville is a little over four hours from Asheville/Smokies. Long weekends possible by car. The Hocking Hills and Hoosier National Forest and Lakes Michigan and Erie are nice, but not in the same league.

Chris,

You’re alluding to what may be the “B” factor, as in boring. I’ve never been to Columbus, but is it? I found my way to a symposium in Austin, partly because I was curious about the place and wanted to see it. Same with Memphis. “Keep Austin weird” and “Austin City Limits” do that.

Columbus sounds like a nice solid place, but if you’re young and single, what is there to do? Coffee houses and local art exhibits, at the mid city level, go only so far. What is “discoverable”?

Exactly, Rod. Not for those who want a “scene”.

But not everyone wants a city that doesn’t sleep. Midwestern “mid-cities” offer a quality of family life, and they offer amenities that tend to reinforce it. Things like zoos and Children’s Museums and science museums instead of nightlife and a scene. Affordable single-family housing. Parks and trails. Not edgy or cutting-edge; moderate. Not too wintry and cold, not too hot all the time; moderate 4-season climates (today’s subzero start notwithstanding).

It appeals to a younger person with a certain long-term vision, one who sees a life like that 5 or 10 years down the road. It would be hard to bring a coastal transplant to Central Ohio or Central Indiana…but not a returning native.

“I agree the potential is very high but there’s something I can’t quite put my finger on about Columbus. It’s related to my observation that Columbus checks all the boxes but seldom innovates or sets the agenda. I think that’s a symptom of something.”

It’s an Ohio thing.

Columbus is a branch plant, back office place for the nearsourcing of medium skilled work from big high-cost metros. It doesn’t have the corporate headquarters, R&D, etc. to bring those who drive corporate decision making. No one is heavily enough invested in Columbus to make it worth their while to consistently push for its overall development. The success and scale of Nationwide’s investment in its headquarters town shows what can happen when people and businesses ARE more heavily invested in Columbus. Being so young, Columbus just doesn’t have the critical mass of such investment to take it to the next level; at least not yet.

Chris,

I grew up in what I then considered to a boring, mid-sized city, Portland, which did not have the salt-water or the university-related attractions of Seattle. And it was somewhat boring, in the city. The saving grace was that it had a wealth of natural places within an hour and a half drive- Mt. Hood and the Cascades, the Columbia Gorge, the coast, and hiking and bicycling in the Willamette Valley, and as a youth of the 70’s I explored these with others. When the time was right later in my career I moved back to the city, partly out of the loyalty and connections to “hometown”, but more out of an attachment to the natural surroundings and what they had to offer on the weekends. Over time, the kinds of people drawn there by the surrounding environment has made the environment of the city itself better, especially through the preservation of natural spaces in the city and the expanding network of trails throughout those places, including bike trails along the creek bottoms.

Lacking those natural areas, Columbus and other places like it will have to work extra hard. Going to college in the Bay Area, I met kids from the midwest who said they weren’t moving back there, they were too taken with the Sierras, the California Coast and the open spaces around the Bay Area like the Berkeley Hills and those above Palo Alto. There is a brain drain going on in the Midwest, and the Midwest cities, for better or worse, have a stiffer challenge than West Coast cities that may be no better on the other “urban” measures. I don’t know how they can compete, but given the relatively poor job most cities do at both crafting and implementing economic development policy, a focus on the basics– education and business support– is the logical starting place. It would give Columbus and other cities like a comparative advantage in what most matters.

By the way, I don’t believe that having large corporate headquarters is essential to growth. “Homegrown” is more important. Big companies grow up and move away, particularly through corporate take-overs. Better to have a larger stable of mid-sized companies, anyone of which might grow, and all contributing to a larger leadership pool.

I somewhat disagree on the lack of assets presumed for Columbus in these posts.

Yes, no oceans, warm weather or mountains is a big negative.

As far as corporate HQs, Columbus has more Fortune 1,000 HQ’s per capita than any other city in the U.S. Translation-the city is pulling above its weight in corporate HQs. Unknown to many-Columbus is a major hub for fashion-yes fashion, with several of the most popular mall stores having HQs here-Limited, Abercrombie, Victoria’s Secret, Bath & Body Works, etc. It’s a major insurance hub. We have several large tech companies here, speaking of which…

Eds & meds? OSU does more research/year in dollars than the University of Austin. Batelle is a major research institute, and stalwarts like Cardinal Health, Chemical Abstracts and the Online Computer Library Center may seem boring, but they are tech heavyweights in their fields and well-respected.

Even the cultural comments are not totally accurate. What Columbus doesn’t have a ton of are what I call macro-fauna cultural institutions- major, visible arts institutions, major sports teams, things like that-I won’t deny that. However, the city is a place that has a very high density in what I call micro-fauna- a large variety of restaurants, cafes, independent shops and a burgeoning indie arts scene. I highly doubt that Austin and Portland have a significantly greater proportion of high arts institutions. They are ahead in the “microfauna” category, but not by half as much as many think, and besides, I think most people live in those cities for the everyday stuff-not the big league amenities. Otherwise they would all be in New York.

On top of that, Columbus IS a major back-office center-not a bad thing.

This all brings me back to my original post-why Columbus isn’t punching with Austin and Nashville and Portland in terms of income and population growth. It really wasn’t that long ago that no one knew anything about Portland or Austin. It was the early 90’s when these cities popped up on the radar. Before that most folks had a hard time finding them on the map, much like Columbus today.

Aaron may be correct-it may be cultural. I do see your point, Aaron, about Austin having to compete with Houston and Dallas. I do think Austin had one built-in advantage-it’s a cultural bastion of liberalism in a red state. Columbus is a moderate city in a state that balances out as moderate, even though it has some hyper-partisan areas.

So Columbus has everything and the standards and models of American metros simply cannot be applied to Columbus. Got it.

I don’t know about Austin, but the seeds of Portland’s growth were sown in the 1960’s, when it began to emerge as an “environmental” or green center. Go to high school there in the early 1970s, I could ride downtown on the state’s first dedicated bikeway. The battle to keep the beaches public, staged in the mid 1960’s was really the turning point. Then came the Willamette River clean-up, the bicycle bill, the bottle bill and land use planning, all passed between 1972.

But it wasn’t this legislation that made the place. It was the people that were drawn here because of the ethic it demonstrated to the rest of the world. No young person is going to aspire to living in the same city as Victoria’s Secret or the Limited, anymore than they are going to chase Proctor and Gamble to Cincinnati. Big companies, big business just doesn’t pluck at the heartstrings. It doesn’t say, “save the world” or “there’s another way of doing things”. A book on the Northwest, Ecotopia, published in the 1970’s, did send that message out across the country to young people.

And yet it took the housing melt down and the decline of the timber industry in the early 1980s’ to really open the place to new leadership. Other than some Japanese tech firms and Intel, there wasn’t a ton of new industry that came in. A lot of what grew back was homegrown. That and the desire of electrical engineers to get out of overcrowded and high-priced Silicon Valley. All of those people moving there for the outdoor lifestyle (“Silicon Forest”) brought a lot of skills that eventually found their way into different companies. The liberal arts kids went to work for Nike and its ad agency, Weiden and Kennedy. What was underlying all this growth? The image of the place as green and manageable put forth in Callenback’s book, Ecotopia. It didn’t happen overnight. The image started growing up more than 50 years ago with those battles over two gubernatorial candidates, and who could save for the public the beaches that everyone liked to go to. There’s actually a video about this called, “The Politics of Sand”.

P.S. People are always looking for simple measures of what drives success, like GPA’s for colleges, or number of corporate headquarters for business. Those are retroactive, backward looking measures. They don’t really show what caused that success in the first place. and the things that gave rise to that success may no longer be there for the success stories of the future. We’re no longer in a 1950’s, highly centralized, command-and-control economy, a hang-over of WW II production methods. We’re in a highly atomized, world-market economy, in which the ability to attract and retain talent is everything.

The risk is commoditizing “talent”, as if all talent is twenty-something hipsters, or thirty-something outdoor adventurers, and trying to go all “Portland” everywhere.

Time for the economist in me to re-surface: People, individuals, will go where their personal “utility bundle” is maximized. Some may value inexpensive housing more, and head to mid-continent cities. Some may value a family-centered (vs. nightlife or adventure-centered) environment.

No city or metro will “hoover up” all the available talent, but cities and regions will have to be very clear about the bundle they have on offer. An atomized world allows lots of customized bundling opportunities.

Chris,

I agree to a point. Young people, for the most part, want to mate before they settle down. I don’t know many young people who grew up in 4H with a hankering for farms. Downtown Mountain View and Redwood City are buzzing with young people making money, driving cars, and setting up dates for the weekends at the beach, in the Sierras, or walking the SF waterfront.

The question is one of both money and talent attraction. Portland is getting the talent, but it doesn’t have the jobs to create wealth for young people. That’s why, in the 80’s, they went to Phoenix, Dallas and Atlanta. Now, for at least the tech professions, they’ve got choice of places that are more urban, and that’s a great way to meet other young people.

If I were Columbus, I’d be looking at Pittsburgh very carefully. It’s the next Portland, and it’s got an underyling industrial base. Richard Florida’s tune on that place has changed the last ten years. A decade ago he said it was too socially closed to draw the young, too discouraging of entrepreneurship. Have those facts changed? If so, how?

Ah, Pittsburgh. I’m going to steal some of Jim Russell’s lines.

Some of the renaissance can be attributed to boomerangers…returnees.

Some of it can be attributed to assets that were always there but literally and figuratively shrouded in coal smoke: CMU, Pitt/UPMC, Duquesne, PPU.

Some of it can be attributed to the death of heavy industry, and the lack of opportunity/jobs for the uneducated and unskilled. Many of the jobs in eds/meds require advanced degrees.

Some of it, conversely, can be attributed to being the biggest city in northern Appalachia, which is also the Eastern US shale-gas region. Like Texas and North Dakota, the northern Appalachian region is sitting on massive shale gas and oil deposits. Natural resource extraction and processing made Pittsburgh rich the first time, and the back-office and support capability still existed; this is a replay, just as in Texas.

I think their story, in short, is that the city died back to its green shoots and is growing again on the strength of old assets. (I’d assert Florida’s “closed-off society” literally aged and died with the steel mills’ pensioners.)

Chris,

Those are very like the things that happened in Portland, where the newspaper had to say “good riddance” to the departure of timber giant Louisiana Pacific by admitting that the company had cut and run. Until that happened, everyone deferred to the old but no longer strong industries. Sounds like the same thing happened in Pittsburgh with steel.

Communities have various assets to work with, but in trying to please the powers of the status quo, they frequently contort themselves or overlook other actions that would generally build their base but may not give preference to the dominant players. Pittsburgh has something to work with, but it took steel’s departure for it to look at how to build on those other assets, literally, because it had to.

I don’t know what’s in Columbus. It seems like kind of a second city. Maybe that’s where it’s comfortable. It if wants to be a “first city” of some kind, it first needs to decide which kind. Pittsburgh has world-class strengths in computing and robotics. Columbus…?

Pittsburgh’s strengths grew directly out of its universities, especially CMU. One might reasonably expect the same in Columbus.

Ohio State is a huge university, but to an outsider (me) it seems mainly to be distinguished by its athletics.

Rankings checks show that three other Big 10 schools have top-10 undergrad engineering programs, but not OSU. Its business school is in the middle of the Big 10. The ag school is behind Wisconsin, Penn State, and Purdue. They are in the middle of the Big 10 in pharmacy.

The university may be solid all around, but in key professional fields it is behind the state universities in neighboring states; OSU won’t attract nearby out-of-state students who get a better deal and a more valuable degree at home. This might account for some of Columbus’ lag: no imported talent pipeline.

The city’s “business map” shows this, as its homegrown/grown up Fortune 500 companies are retailers and wholesalers (Big Lots, Limited, Cardinal Health) plus a major insurer (Nationwide). No big pharma, no big med-device, no big ag, no big tech.

Indy actually has three of these four going [pharma=Lilly, ag=Dow Agro and Elanco, tech=ExactTarget a SalesForce company], and the orthopedic implant capital of the world is elsewhere in the state in Warsaw.

Chris,

The University of Colorado’s consistent ratings as one of the nation’s top party schools shows that academic excellence isn’t essential to pulling talent. Boulder has fit young people and great hiking.

Of course, Boulder’s draw is more than just mountains. It does have a spectacular setting, with a creek running through the downtown, but it’s also got some federal institutes in basic research, a strong tech base in storage and solar, and a college town openness that fostered companies like Celestial Seasonings back in the 1970’s. In other words: pretty+hip+tech. Makes you wonder how Madison can compete, but it does. How, through force of personality?

Isn’t it interesting that Columbus has received so little defense on here from local boosters. If we were contemplating the many reasons for the failures of Cleveland or St. Louis , this forum would devolve into a proverbial holy war. Is this evidence of the lack of investment, emotional and otherwise, in Columbus? Are there just not enough people who care enough about Columbus to push it to the next level as I’ve suggested already? Does this matter?

Matthew,

It may be that the people there are not aware that this discussion is going on. That may be the urban focus of this blog, or it may be that they are simply “not in the game”, that they are not tracking and reacting to how their image is portrayed elsewhere. While it is well and good to keep your head down and concentrate on doing well, any public entity, especially one desirous of drawing money and talent, should be tracking its image. That’s one of the reasons I so often wonder at these videos: so often they don’t seem to deal with the perceptions that are already out there. Granted, you may want to change those perceptions, but the way to deal with them is square on, by showing how they are wrong or how you have a plan to change the reality. Lee Iacoca did this when he turned around Chrysler.

You make my point. No one in Columbus seems to care that these discussions are going on. They don’t see any overlap between their individual interests and those of metro Columbus. I don’t think it’s not caring about the image of Columbus, I think it’s not caring about Columbus itself. I lived there for 5 years and time and time again, as soon as I got to know some one they left town. I think that too few are invested in Columbus as a place to work for its interest as a place. I think that is why Columbus hasn’t moved out of the second-tier to be like Austin. People need to see some reason to stay in a place. It has to offer something other places don’t.

Matthew,

What is missing that is not giving them more reason to stay? Is it something in the nature of the work or work styles, a sense of civic-belonging, after-hours attractions and activities, or something else? This question of “attachment” is important to both attraction and retention of residents and firms alike.

Rod, Matthew Hall is a hard core Cincinnati partisan. I’ve noticed that old major river city dwellers tend to have a bit of that New England attitude we’ve been talking about. They are never going to give new growth cities like Columbus their due.

I had an interesting discussion this weekend with a friend who grew up in Nebraska. She’d go back because she has family there and it is the archetypal landscape she grew up with, a land of wide fields and big blue sky. That said, the door has been open on the barn for a long time, and a lot of those horses are not coming back. The question, in terms of talent attraction, is what they’re going to offer to attract those who will backfill, especially those with high skill. My friend has a PhD in bio tech. She is teaching science at a local private school. Her husband, also in bio tech, continues to work in the industry. Seattle is a major center for this. They could move back, but it would mean longer trips on the plane for him. So, thinking about the industries Columbus is strong in, what can it offer to overcome the competitive coastal cities’ advantage in “play”? Maybe the job and educational opportunities will be just that much better. My guess is the two need to work together to permanently attract talent young people to the city while they are still in college or graduate school. That’s Talahassee’s strategy.

Sorry, I think that should have been “Gainesville”.

Good question, Rod. What DOES Columbus have that no or few other places have? What combination of jobs, costs, industries, location and social, cultural, and educational offerings does it have that no one else has? The answer to that question is the answer to the larger question about its recent and future growth.

Aaron, do my past postings make my question about Columbus meaningless or unimportant?

I’m just saying that you’re a partisan of Cincinnati. Post all you want. I just think it would be nice if you occasionally wondered why places like Columbus have been running rings around Cincy in job and population growth for a long time if they don’t have anything good on offer. Though I think its growth trajectory could be higher, Columbus is at least semi-booming, albeit in a Texas sort of way.

I know why Columbus has grown; cheap southern-style development. Relatively low wages and cheap infrastructure, and a few special advantages that come with being a state capital and a college town are basically it. I’m wondering why it hasn’t moved up the chain of innovation with all the resultant increases in wages and property values. It has quantity, but where is the quality. That’s my question and I’m stickin’ to it.

The measure of economic value is GDP per capita. Columbus is in the middle of the pack, 7 out of 12, for that among large Midwest metros. Cincinnati is #10.

Keep in mind that per capita income is also heavily affected by college students who don’t tend to earn much income. Columbus would probably be even higher on GDP too with fewer students, though the university high value spinoffs may offset this effect.

With a few exceptions, lots of suburban Columbus seems lacking in quality development. You have to wonder how that will wear over the longer term. Doesn’t Columbus suffer the same way Indy does with a lot of problems in the inner-ring of “townships” surrounding the core of the city?

Then why aren’t wages significantly higher in Columbus. Who is realizing that wondrous GDP in Columbus? Is Columbus appealing because it allows capital to take back a greater share of its profits leaving less for workers. That explains why Columbus is appealing for capital and why it might not be so appealing to wage earners.

Actually, personal income is made up of three components: earnings from work, investment income, and transfer payments. If you look only at earnings, Columbus per capita earnings are higher than Cincinnati. (Average weekly wage, from a separate data set, is about $10/week lower in Cbus, but that excludes self-employment).

It all counts. Who receives investment income and transfer payments matters. Where would Florida’s economy be without transfer payments? Is investment income concentrated in certain places? Does this help to explain metro economies?