This article is part of The State of Chicago.

I now want to transition from a look at historical and current conditions in Chicago to a defense of a couple of my more controversial diagnoses that attepted to explain the problems behind Chicago’s weakness in recent years. These were my observation that Chicago lacks a “calling card” industry, and my claim that Chicago, while a global city, is weak enough in this dimension that it cannot rely on that alone to sustain it.

Today I’ll look at the former. In some rankings I’ve seen, Chicago has the most diverse big city economy in the United States. The flip side of this is that unlike with New York and finance, DC and government, LA and entertainment, etc., Chicago lacks a signature industry that is capable of generating significantly above average returns. That helps explain why on various quality measures (like GDP per capita) it greatly underperforms. Chicago is simply not the epicenter of any important 21st century macro-industry that is capable of generating super-sized returns. I gave a more detailed treatment of this some time ago in a post called “Chicago and the Epicenter” should you be interested. (You’ll note from that post I was already thinking about this series over two years ago).

Pros and Cons

Now being diverse vs. being concentrated in a particular industry has both pros and cons. If you are overly concentrated in a single industry, then you are vulnerable if that industry nose dives – just ask Detroit. Really the big difference between Detroit and Silicon Valley is that the latter’s signature industry is still going strong. Also, excessive specialization in one high value function can actually drive everybody else out as the highest value use bids up real estate into the stratosphere. Perhaps we might say that it operates with positive reinforcement, which isn’t always a good thing.

Very diverse areas, by contrast, aren’t as vulnerable (in theory) to big collapses. It’s slow and steady wins the race, with fewer boom and bust cycles. So there’s definitely value to diversity. Of course the flip side is that you don’t have that unique magnet for talent. No one has to do business in your city. You generally create average level returns and incomes. Indeed, we see all of this in Chicago. And having a diverse economy did not protect it from severe consequences in this downturn.

Does Chicago Want to Just Have a Diverse Economy? No

Some folks touted the diversity of Chicago as a great strength in response to my article, but deep down I don’t believe anybody really believes it. Everything every civic and economic development person is doing every day is predicated on the desire to be specialized.

Consider the trivial example of the culinary arts. Chicago likes to view itself as a rival to anyone when it comes to cuisine. Is this just a matter of Chicago being big? That is, that It has exactly as much fine dining as it is “supposed to” for a city of its size? Is this how locals sell the food scene? No. The entire idea is that Chicago is a special place, where it not only has a great food scene because of how big it is, but because it has something special that let’s it punch above its weight.

We see a similar dynamic at work in the tech sector. Chicago is determined that it wants to be a major American tech hub. Does this mean that it simply wants it’s “fair share” of tech for a city its size? The rhetoric doesn’t sound like it.

For example, at Tech Week Rahm Emanuel noted that Chicago is known as the Second City, but that “three years from now it’ll be known as the startup city if we do everything right.” The recent announcement of Google moving Motorola’s operations from Libertyville to downtown is also portrayed as boosting Chicago’s tech ambitions. Clearly, talk to any tech booster in town, and you won’t here how Chicago is mere “average” in tech for a city of its size – or that ranking as such is their ambition.

Also, if you look at Emanuel’s own economic plan you’ll see that the #1 item in its analytical framework is “Economic Sectors and Clusters.” What is a “cluster” except an industry where a city has a higher than average concentration (i.e., specialization) in that industry? Indeed, the plan uses location quotient, a standard measure of jobs concentration, as a tool to identify areas where Chicago is specialized.

The challenge is that these specialties are pretty weak and pretty general. It would have been nice had the various recent analytical looks at Chicago’s economy looked at how it differs in terms of a lack of high value specialization vs. other tier one cities.

Now, of course Chicago does have some specialties – logistics (particularly around rail/intermodal) for example at the macro level and say the design of super-tall skyscrapers at the micro. However, these either don’t necessarily generate significant high end returns or simply aren’t that big in aggregate.

In any case, it’s certainly not valid for Chicago boosters to cite economic diversity as the city’s key strength on the one hand while everything they do is designed to create specialization on the other. I’d like to see the rhetoric remain consistent.

Why a Calling Card Industry Matters

If you look at how businesses behave, you start to see why a calling card industry is important, especially for a city like Chicago. For example, former GE CEO Jack Welch said he only wanted to be in a business if he could be #1 or #2 in that market. Warren Buffett likes to talk about what he called “wide moat” businesses like Coca Cola – ones that have built barriers against competitors such that they retain significant competitive advantage over the long term and thus can generate superior economic returns.

It’s difficult for a city to generate those types of returns if it has no real competitive differentiator. If there’s nothing that enables a particular industry to thrive in your city better than somewhere else, then really you are just playing a commodity game. Those types of businesses tend to be brutal, low margin, and dominated by producers who have the lowest costs and most operational efficiencies, Wal-Mart for example.

Clearly cities like Dallas have mastered that market. Chicago is not a low cost producer and hardly as business friendly or efficient as many other places for Joe Average type businesses. So why are businesses going to locate there? There really isn’t a great answer to that question right now. The entire focus seems to be on global city/talent magnet/Loop. That’s an important piece of the puzzle to be sure – and not to be neglected. But as I’ll demonstrate in subsequent pieces, it’s not enough.

Often cities carve out a specialized basis of appeal based on the unique agglomeration environment in a cluster or major signature industry. If Chicago doesn’t have that, and isn’t the cheapest place to do business, it has to find another basis of competitive advantage to build its fortunes on.

I won’t rehash this since I already addressed some of this in a piece I called “Chicago’s Structural Advantages.” The idea is to look at structurally unique factors about Chicago and attempt to find ways to leverage them. The biggest advantage Chicago has it that it’s the only large, traditionally urban type city in the US interior.

Now, the city would no doubt say that it’s current talent/Loop/global city strategy is based on this, but I really don’t think it is. For example, the push into tech is basically a me-too type effort and I don’t see Chicago as well placed to punch above its weight in digital type startups. I’m sure it can do well to some extent, but it should. Chicago is the third largest city in America after all. That alone dictates it should be big on an absolute basis in most things. But I don’t see it as Silicon Valley II. For all the economic development “usual suspects” like tech, life sciences, and green industry, I suggest Chicago’s best strategy really is to get a “fair share” of these and not worrying about trying to build a fortress franchise.

My biggest recommendation instead is to focus on creating what I call “Professional Services 2.0” That is, the next generation of professional services in America. As I noted previously, Chicago may be the best place in America to fly people around the country. Why not leverage that?

Indeed, we are seeing an uptick in professional services, but I see this as a natural revival, not as a result of any particular strategy on Chicago’s part. Which is fine, actually. But I also see weak spots. For example, the Indian outsourcers like Infosys, Tata, etc. don’t seem to see Chicago as their main US hub (or at least they didn’t last time I worked). Newer models of onshore consultancy seem not to be coming out of Chicago, but out of traditional innovation hubs. For example, firms like Slalom and Point B are both based in Seattle.

This suggests Chicago has work to do, but it doesn’t seem to be really focused on this. Professional and business services is part of Emanuel’s economic plan, but is clearly subservient to headquarters attraction. There needs to be much more focus on services for its own sake – Chicago should absolutely OWN the space.

In any event, that’s one example of how Chicago might move forward.

Diversity and Specialization Not Necessarily Opposed

Lastly, one final note on diversity vs. specialization. Sometimes diversity and specialization are posited as opposites, but in some cases it isn’t necessarily true. You can have a diversity of specialties, for example. That is, your city has multiple areas in which it has a dominant type position. I supposed you could call it a specialization conglomerate, though that’s a corporate approach that’s a bit out of favor.

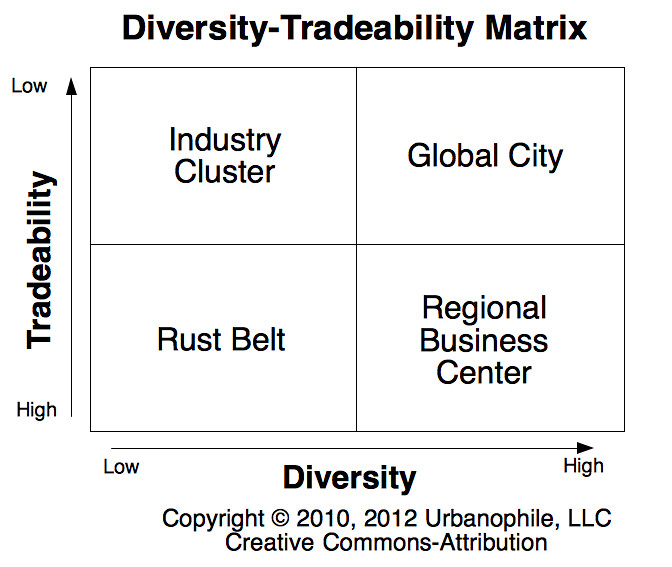

I’ll illustrate this using a dusted off 2×2 matrix I put together a while back called the “Diversity-Tradeability Matrix.” It doesn’t look at specialization per se, but rather tradeability, or the ability of an economic activity to be performed elsewhere (such as offshore), which we might view as really the core of what we’re hoping to get at through specialization – the wide moat position.

Here’s the matrix with the resulting four typologies of cities:

For Chicago, I’d argue the city most belongs in the Regional Business Center category. It’s mostly a diversified regional capital like Atlanta moreso than a global city like New York, though of course it has global city parts to it. But it’s a Regional Business Center with a high cost profile, which creates the challenge.

In your model it seems that Chicago would have to focus on being a regional business center since most other midwest metros are moving toward industry clusters. Bio-medical related tech, transportation engineering, and increasingly transportation/logistics in Cincinnati, agro-tech in St. Louis, and energy and manufacturing related tech in Pittsburgh, etc. What does this mean for companies like boeing and motorola being in chicago?

Hi! Although I’ve been taking a peek at your blog off and on for years, and rather admired your article for the “City Journal” this is a first time comment on your blog.

If I remember correctly, I’ve gotten the impression that you’ve read and admired, at least to some degree, Jane Jacobs’ “Death and Life of Great American Cities.” As you probably know, subsequent to “Death and LIfe . . . “, Jacobs wrote a number of other books that focus even more specifically on cities and economies: “The Economy of Cities,” “Cities and the Wealth of Nations,” and “the Nature of Economies.” (Her other major books also deal with cities and economies, but less directly.)

It just so happens that I’ve very recently re-read both “Cities and the Wealth of Nations” (last week) and “the Nature of Economies” (which I finished yesterday) so these books are very much on my mind — and your post really jumped out at me. Since your arguments seem to come out of orthodox urban economics, I wonder if you’ve read these other books and have consciously rejected her arguments, or if you just were not sufficiently impressed with “Death and Life . . . ” to read her other books?

If it was the latter, I would greatly recommend them as they make some very interesting arguments and Jacobs discusses a number of startling historical examples — and her books are, as usual, very entertaining to read just for the examples (whether you agree with her arguments or not).

As one might imagine, in her books Jacobs comes out very strongly in favor of the benefits of diversity over specialization (e.g., of Birmingham over Manchester) — and in a way you could say it is the main theme of her books on economics. In your post, you also discuss the dangers of overspecialization, but Jacobs’ arguments seem to be more far reaching. Jacobs also writes about “economies of location” trumping “economies of scale,” and a great deal about the importance, in her opinion, of cities engaging in a process she calls “import-replacement” (which is different from what others have called import substitution) — and of cities being diverse enough to be able to engage in import replacing and also diverse enough to be able to generate NEW exports when other cities eventually replace a city’s own exports. (Detroit, might be a great example of a city that overspecialized and didn’t do enough import-replacing to stay economically healthy.)

With regard to “calling card” industries, it seems to me that Jacobs would say that calling card industries are best left unplanned, to bubble up from healthy basic economic processes rather than as a result of a conscious decision to develop them.

But Jacobs makes a much, much better case for her arguments than I do, so hope people aren’t turned off by my quick summaries! One thing, although “the Nature of Economies” was written many years after the “Economy of Cities” and the “Cities and the Wealth of Nations,” in some ways I find it a great introduction to both books. So if people are inclined to read these books, I think it might help to read “the Nature of Economies” first — plus it’s short, written as a dialog (short story or novella), and I think it is the most “entertaining” of her books on economics.

Benjamin Hemric

July 29, 2012, 9:05 p.m.

Benjamin, thanks for the comments. My recall is that Jacobs was more interested in having a plethora of small firms rather than a few, large integrated concerns moreso than she was having lots of different industries. She was positive on diversity in many contexts – for example, she noted the diversity of suppliers and types of products available in big cities – but I don’t recall that she advocated an economy that was a mirror of the nation as a whole or anything like that. If she did, I’d appreciate you refreshing my memory on it as it’s been a while since I read her books.

For a city to create above-average wealth, it must make something unique and sell it to the world. If your products are just average, you will make average money. If your products are above average, you will make above average money.

To be above average, you must have both natural and man-made advantages. Chicago has the logistical advantages you describe. To capitalize on this, Chicago needs to add value to the goods that pass through its hands. Perhaps it becomes a repair or an assembly center. Manufacturing. Something that local people putting their hands on goods adds value to.

How do you create this value of “the putting on of hands”? Through education and training. Apprenticeships. K-12 and higher ed programs that support this. Yet Chicago’s universities are distinctive in manufacturing-related fields. The premier universities- Northwestern and Chicago- are strong in law and marketing and the liberal arts but are not exceptional in engineering. IIT has little or no national visibility. Even so, this may not be a case of needing to train more elite engineers (that talent is remarkably mobile, just ask Seattle, which imports much of its tech talent), but of making sure that the line worker is better trained. If Chicago had more of the journeyman skills that cities in Germany and France do, would it do better? Undoubtedly. Unfortunately, if there is one thing Chicago is famous for nationally in education, it is the poor quality of its public schools. That turn-around will be slow, challenging and expensive, but it is the foundation of a talented workforce. To ask how Chicago can compete and to ignore basic education is to ignore the obvious.

typo correction: Chicago’s universities are not distinctive in manufacturing related fields like engineering, at least nationally. Which schools are? Stanford, MIT, Carnegie Mellon, University of Michigan, Rochester, Georgia Tech,

“State of Chicago: Lacking a Calling Card Industry”

And believe me, that’s a good thing.

Houston is nothing more than one giant boom-bust cycle. NYC has placed ALL of their eggs in the financial basket. That’s a big mistake in my opinion. Because those institutions are going to be shedding workers at a rate never before seen. They are simply living on borrowed time as the age of the institutional investor matures and computer-modeling basically makes them obsolete. Funds are going to be managed by far fewer people and regional banks are becoming far more attractive.

“Clearly cities like Dallas have mastered that market. Chicago is not a low cost producer and hardly as business friendly or efficient as many other places for Joe Average type businesses.”

Texas is number 1 in minimum wage jobs with zero benefits. It has nothing to do with “mastering”. Texas is cheap for a reason.

“But I don’t see it as Silicon Valley II.”

And nor should it be. If you want to look at something that is completely unsustainable, go live in Santa Clara County. How are you planning to create a start up when your new hires demand 150k/year, are relegated to living in shoebox with 2 other people, and 50 percent of your salary goes towards housing?

“Indeed, we see all of this in Chicago. And having a diverse economy did not protect it from severe consequences in this downturn.”

Strange. I don’t know of any city that was protected from the downturn with the exception of Fargo, North Dakota.

Washington D.C. was protected from the downturn.

There’s no doubt that large-scale clusters really benefit some large metros. Tech in the Bay Area, finance and publishing in NYC, energy in Houston. And smaller clusters benefit smaller metros, aerospace in Seattle, tech in Austin, medical devices in Minneapolis.

Obviously, San Francisco and NYC are global hubs in a businesses that are completely electronic and permit truly global nodes. Ignoring NYC and global finance, does Chicago have a peer that you can compare this too? After a certain size, nodes are limited by the size of the business and can’t really measured as a function of city population. Chicago has specializations in healthcare (Abbott, Baxter, Allegiance, Siemens, Walgreens, Takeda, Cardinal, etc) and Food (Kraft, Sara Lee, Quaker Oats, etc) that would be dominating if they were present in, say, Charlotte or Nashville. Aaron, you’ve mentioned entertainment in L.A. a few times as a “specialization” and I think that’s a very apt example. Entertainment is a big deal isn’t *that* important to the diverse L.A. economy, not like . L.A. is a megacity, and I don’t think business focuses can be measure in a region like that the same way it can in smaller cities. You can compare L.A. to Chicago, but I don’t think it’s helpful to compare L.A. to Austin.

I found Ed Glaeser has repeatedly and thoughtfully arguing that one of the bigger problems facing New York is that it is too dependent on finance and insurance and that its endanger of becoming a one industry town.

http://www.city-journal.org/2012/22_2_ny-finance.html

http://www.city-journal.org/2008/eon1027eg.html

While Chicago has some problems I think the big problem isn’t a lack of over-concentration in a specific industry but rather that the area is too dependent on large fortune 500 employers. What I am more concerned about is the health of the smaller middle sized companies. What the Germans would call the Mittlestand companies.

I think its these middle size companies that Chicago has a chance to attain competitive advantage. As you pointed out Chicago is a leading site for logistics, it has the rail network and the air hub. It also has the large concentration of professional services. If you were a small manufacturer that wanted to go global Chicago has a lot of advantages. If you needed to consult experts in international tax or how to hedge currency risk, you can find that locally in Chicago. Your sales team can find direct flights to almost everywhere in the country and can ship goods to most of the country in a day. For middle sized companies these are huge advantages. Moreover when your company is ready to start exporting globally, Chicago still also has direct flights to most of the leading cities on the planet, so a small company sales team can still be mostly located in one location but cover most of the globe.

Bigger companies can afford to operate from multiple locations on the planet, but that creates its own management and control problems. But for middle sized companies Chicago offers huge advantages. Moreover some of these middle size companies will grow into something substantially larger over time.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mittelstand

Aaron, thanks for the quick reply! (And I hope you don’t mind my use of a dialog format; but I find it helps me to write quickly and stay focused.)

Aaron Renn wrote:

My recall is that Jacobs was more interested in having a plethora of small firms rather than a few, large integrated concerns[,] more so than she was [in] having lots of different industries.

Benjamin Hemric writes:

Which Jacobs’ book or books are you thinking of? Having just re-read “Cities and the Wealth of Nations” and “the Nature of Economies,” these are the books that are freshest in my mind, and these were the ones I was thinking of. While Jacobs, in general (in all her books on economics) does make the point that small businesses are more important for a city’s economy than are generally acknowledged by orthodox economists, in these books, at least, her focus is more on other issues — and the importance of economic diversity for a city’s continued economic growth is one of them.

On page 106 of “The Nature of Economies” (paperback edition) for example, Jacobs (as Murray, one of the characters in the book) has this to say about overspecialization:

“But although the close empiric connection between economic diversity and [economic] expansion was observable in [Adam] Smith’s time and has been observable ever since, the connection slid unnoticed past economic theorists arrested in their obsession with whether demand leads supply or vice versa. Smith himself was partly responsible for that blind spot. He led himself and others astray by declaring that economic specialization of regions and nations was more efficient than economic diversification; his mistake came of flawed assumptions and extrapolations concerning division of labor.”

But let me also quickly add, that it seems to me that Jacobs would heartily agree with you that a healthy, diverse city economy is also likely going to have “specialized” industries — this can be very good for a city’s economy and is not at all bad. (It’s good, for instance, if the specialization is a natural outgrowth of the city’s generalized economy and not something that has been “imported” or “lured” from elsewhere.) What Jacobs is saying is dangerous is for the CITY itself to “specialize” in a narrow range of industries; she isn’t saying that its dangerous for industries within cities to develop specialized niches.

– – – – – – – –

Aaron Renn wrote (added numbering between brackets is mine — BH):

[1] She was positive on diversity in many contexts — for example, she noted the diversity of suppliers and types of products available in big cities — but I don’t recall that she advocated an economy that was a mirror of the nation as a whole or anything like that. [2] If she did, I’d appreciate you refreshing my memory on it as it’s been a while since I read her books.

Benjamin Hemric writes:

Regarding [1] — I would agree that Jacobs, as far as I can recall (and I haven’t re-read “the Economy of Cities” in a while), does not say that a healthy city economy should be a mirror of the nation (or the world) as a whole. But she does believe diversity is beneficial for a number of reasons — and for much more than there just being a “nice” diversity of suppliers and products (although that’s a part of it). In “the Nature of Economies,” for instance, diversity is important for the “self-refueling” of economies (i.e., the development of new businesses to replace those that have been ursurped by other cities or have otherwise died out).

Regarding [2] — What struck me about your original post, especially since I’d just re-read two of Jacobs books on urban economics, are the points where I thought Jacobs might say to you, “Aaron, you obviously have the right intentions, but, sadly, you’re barking up the wrong tree.”

Therefore I hope you won’t mind if I briefly point out (in a separate comment — maybe today, maybe tomorrow) where Jacobs writings would argue against your approach or, at least, suggest slightly different avenues.

(To be continued.)

Benjamin Hemric

Mon., July 30, 2012, 9:05 p.m.

Rod Stevens said:

“Unfortunately, if there is one thing Chicago is famous for nationally in education, it is the poor quality of its public schools. That turn-around will be slow, challenging and expensive, but it is the foundation of a talented workforce. To ask how Chicago can compete and to ignore basic education is to ignore the obvious.”

Uhhh…..Rod, ever heard of the suburbs? You know, where the vast, vast majority of the Chicago region’s children are educated? Metro Chicago has plenty of good public schools.

That may be true, but where is most of the young talent in Chicago settling these day? Yep… inner city Chicago. A recent article in Crain’s highlighted how Millennials who are underwater in their condominium mortgages are unable to sell and move out to the ‘burbs as they planned, and so they are now putting pressure on the central city school district to improve its offerings. They may ultimately get what they ask for, but the reality is that many of the center city school students are kids living a latch-key existence of poverty. If you’re Google moving Motorola downtown, and ultimately want to expand and grow that operation to the size that it will have an appreciable impact on the city’s wealth creation, how are you going to hire those kids who are poorly educated? To me the only solution is an aggressive revamping of K-12 education and an interlacing of that system with a higher-ed system that includes apprenticeships and technical training. That’s what the Germans, Swiss and Scandinavians offer, and it explains in part why a country like Denmark, with no appreciable specialty, can get the premiums it does for Bang and Olufsen stereos and blue cheese that would otherwise sell for half as much. They have a value-added economy that rests on the skills of their workers.

Rod,

Probably very few of Moto Mobility’s current employees have been educated by the CPS, and very few of its future employees will need to have educated by the same.

I really don’t understand how the arbitrary boundaries of a city prevent one from finding employees elsewhere. We are talking about recruiting from the suburbs, here, not another part of the country.

Besides, most software engineers and the like are college grads anyhow.

While I don’t disagree that Chicago needs to improve its public school system, urban school districts with a large minority population share this challenge, and Chicago really is not unique in this regard.

For the most part, I don’t share your notion that the CPS plays much of a significant role in the challenges faced by the greater Chicago metropolitan area.

I can only answer for my hometown, Portland, and Seattle, which is where I now live.

When I was growing up in Portland, it had one of the finest big city school systems in the country. I went to public schools there and got a good enough education to go on to what are considered two Ivy League places. With the growth of the suburbs, however, the center city schools have slipped, and now young people with families are more hesitant to live in the center city. The center city there is a major draw for young people from outside the region, for it’s part of the hip lifestyle, but it’s not firing on all cylinders because of the city pre-occupation with building back the schools. Money that might otherwise go for parks, and make the city even more attractive to talent, is instead going into these social services.

Schools are an even bigger issue here in Seattle, which means that even though the population of young childless couples is growing in the city, Seattle remains the second most childless big city in the country, second only to San Francisco. Why? Because the cost of private K-12 education adds $200-300k to the real price of housing. The alternative is taking the bridges and freeways to the suburbs, making these hopelessly choked after 3 p.m. So for those with kids, the region begins to take on some of the congestion problems that have driven talent out of the Bay Area. Yes, the Bay Area is pre-eminent in tech, but it would be even stronger, and arguably more diversified, if housing and living costs there were not so great.

The big issue, though, is simply talent availability. Here in Seattle, Bill Gates and others push for expansion of the visa program because they cannot get enough engineers. Google locates here as close to Microsoft as it can, not because there are operating synergies, but because it wants to steal its talent. Whether the average person knows it or not in this recession, the U.S. has a critical shortage of the right kind of talent. The reason that Austin, Boulder, Madison and Athens are doing so well as places, particularly in software and manufacturing, is that they are minting talent that wants to stay in those cities, especially since they have good public education systems. Can Chicago, particularly in the center city, make the same claim?

Rod,

You are talking about people choosing to LIVE in the city, while Aaron’s discussion is about Metro Chicago’s economic performance when compared to its peers.

This is really an apples to oranges comparison. If the discussion was about Chicago’s (or any big city’s)ability to attract more families into the core, then yes, education and the CPS should be way up there.

Reality is, Chicago is one of the few cities in the US that has a mass transit network large and extensive enough to draw workers in from a very large area encompassing portions of 3 States. Therefore, the quality of CPS is probably of relatively little consideration for companies looking to expand downtown.

Where I do see the failings of CPS coming into play is in those desperate neighborhoods on the south and west sides of the city, but I would say gangs and crime play a much larger role in holding those areas back.

Schools are only as good as the community they serve. If your community is full of violence, drugs, and single mothers, then I guess “the schools” are failing your community. But frankly I think it’s the reverse–the community is failing the school system.

“Schools are only as good as the community they serve. If your community is full of violence, drugs, and single mothers, then I guess “the schools” are failing your community. But frankly I think it’s the reverse—the community is failing the school system.”

This is correct. There is really nothing CPS can do to correct this.

You had some very good points in your article however, you made it sound as though Chicago should already be at a certain place in regards to all of the lastest industry modes. I would say give it time. The fact is Mayor Richard Daley wasted away an entire decade of Chicago’s growth potential. Rahm Emanuel has only been in office just over a year and his intentions are to position Chicago as an economically aggressive city. I think he is well on his way displaying this and way ahead of schedule. He has been a gane changer.

However many changes in the city and states economic and tax structure MUST be corrected if Rahm Emanuel really wants to make Chicago a dominant business city. As it stands we still have a long way to go. Again, Chicago is under new leadership and I attribute the curent mayors position as a major factor why companies are deciding to return to the city. He has given the city positive direction unlike Daley, who was tearing the place to peices. Mayor Daley was a fierce crook who practiced dirty, unfair and dishonest business tactics. On top of that, he had zero business management skills and ran the city like a ponzi scheme. Daley almost killed Chicago. It’s now up to Rahm to revive the city and by the looks of things he’s definitely reviving it. People are returning to the city in droves upon droves (businesses and residents)and the Chicago spirit is back in the streets. The city is vibrant, once again and people are proud to claim Chicago as home! We haven’t had that feeling in a decade.