[ This week is the Thanksgiving holiday in the US, so I’ll be away and enjoying it for the rest of the week. As a holiday long read for you, I’m posting this very important piece about the three generations of black mayors in America and how the timing of the election of the first black mayor affected the trajectory of those cities, with implications even today. Pete is the best writer on urbanism and race that I know and you can read his writings about this and more on his site Corner Side Yard – Aaron. ]

The Monument to Joe Louis, commonly known as “The Fist”, in downtown Detroit. For more than thirty years, the sculpture has been a controversial symbol of black power in Detroit. Source: Pete Saunders

If the cities that elected black mayors during this tumultuous period are ever to move forward, to achieve their potential, they must be released from the purgatory they inhabit.

Just as many people have well-developed thoughts and opinions on the American Civil War but little understanding of the turbulent Reconstruction Era that followed, many are familiar with the 20th Century Civil Rights Movement, yet are far less knowledgeable about the local social and political events that followed it. The Black Power Movement supplanted much of the Civil Rights Movement after the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, with an emphasis on turning social activism into political empowerment. Several cities elected their first black mayors during that period. Cleveland was the first with the selection of Carl Stokes as mayor in 1967. Gary, Indiana followed suit the same year with the election of Richard Hatcher, and the federal government appointed Walter Washington to become Washington, DC’s first black mayor as well. Later, Newark (Kenneth Gibson), Dayton (James McGee) and Cincinnati (Ted Berry) followed suit by 1972, and culminated with the elections of Tom Bradley (Los Angeles), Maynard Jackson (Atlanta) and Coleman Young (Detroit) in 1973. A new era of African-American political empowerment had begun.

Taking a long historical view, it’s clear that the people who became first African-American mayors beginning in the late ‘60s and continuing through today held different views, developed different paths to victory and methods of governance, and had differing perceptions of their skills among their constituents. Mayors elected through about 1975 were often activists straight from the Civil Rights Movement, and were looking for ways to turn the movement into actual political power. The group of black mayors that followed them, from about 1975 to 1990 or so, had more distance between them and the Civil Rights Movement and were less concerned about implementing movement politics; they were more concerned about developing the kind of coalition that could get them elected and help them win legislative victories once in office. The third group of “first black mayors”, coming after about 1990 and continuing through today generally came to terms with a different demographic landscape in most major American cities. Whereas first black mayors elected twenty years prior could dependably rely on a supermajority of black votes in their favor — and an equally large supermajority of white votes against them — the most recent group works in a more nuanced and less racially charged environment. Younger white residents without the racial grievances of their parents or grandparents were returning to cities, and Hispanics were rapidly increasing in numbers. Anyone who would attempt to become a “first black mayor” in that environment would have to develop an appeal that goes beyond racial boundaries.

And yes, the decade that followed Dr. Martin Luther King’s assassination was as tumultuous as they come for America’s largest cities. That period, well remembered by those who lived it as a time of particularly strong urban and social tensions, coincided with the downward slide in momentum of the Civil Rights Movement and the subsequent rise of the Black Power Movement. Older adults likely remember the period well: urban riots, fights over school busing, Affirmative Action battles, efforts to eliminate long-entrenched policies like blockbusting and redlining. Skyrocketing crime, heated debates on the inequity of public services, and the development of a new, rapidly expanding land called “suburbia” that was looking very appealing to a growing number of city residents. Nearly all large cities developed scars during that period. The question is whether they healed, and healed well.

“It’s Our Time”

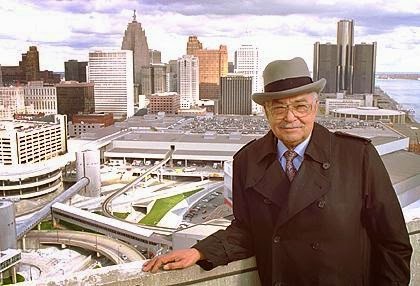

Detroit Mayor Coleman Young. Source: Detroit News

Young became a vocal critic of local leadership after the 1967 riots, and targeted the heavy-handed efforts of Detroit police to reduce crime. Young announced he was running for mayor in 1973 in large part to work to disband the Detroit Police Department’s STRESS (Stop the Robberies, Enjoy Safe Streets) unit. The unit was often mentioned as the initiator of police brutality complaints, and was allegedly responsible for as many as 22 deaths of black residents over a 2 ½ year period. Young ran against John Nichols, the city’s police commissioner and staunch supporter of the troubled unit.

Young won a narrow victory over Nichols in 1973 in a race that was almost entirely split along racial lines in the nearly 50/50 city. In his inaugural address, Young famously told “all those pushers, (to) all rip-off artists, (to) all muggers: It’s time to leave Detroit; hit Eight Mile Road! And I don’t give a damn if they are black or white, or if they wear Superfly suits or blue uniforms with silver badges. Hit the road.” Young maintained that his message was that criminals were not welcome in Detroit; the quote has often been interpreted by white former Detroit residents as a throwing down of the gauntlet, urging whites to leave the city for the suburbs. Young went on to win four more terms in office. He balanced budgets yet struggled to maintain services in a city with a rapidly declining tax base. He remains one of the most controversial leaders in Detroit history.

Conversely, Cleveland’s Carl Stokes and Newark’s Kenneth Gibson may not have provoked similar passions in their respective cities, but they did not fare much better. Stokes obtained his law degree in 1956, served three terms in the Ohio Legislature and narrowly lost a bid for mayor in 1965. His eventual win in 1967 garnered him plenty of national attention as he became the first African-American mayor of one of the nation’s ten largest cities. He was successful enough to pursue and win a second two-year term in 1969, but his tenure in office was characterized by constant feuds with the Cleveland City Council and the Police Department. Stokes left office at the end of his second term. After studying civil engineering in college, Gibson worked for nearly two decades as a structural engineer with the New Jersey Highway Department, the Newark Housing Authority and the City of Newark. He pursued the mayor’s office as a reformer wishing to restore honor to the office following the corruption scandals of incumbent Hugh Addonizio. Gibson won in 1970 but perhaps his attachment to people like Newark poet and playwright Amiri Baraka, who challenged Gibson to push the city’s corporate interests to take a more active and responsible role in the community, served as a lightning rod to the city’s remaining middle class element. Gibson was elected to four terms, but Newark’s slide continued unabated.

Black National Political Convention

It’s probably fair to say that the political pinnacle of the Black Power era took place between the elections of Gibson and Young, with the advent of the Black National Political Convention in 1972. Held in Gary, Indiana and hosted by Mayor Richard Hatcher, delegates from the entire spectrum of black leadership convened to establish a black political agenda for urban America. More than 8,000 people attended the three-day convention, with 3,000 selected to be voting delegates. Newly elected black officials attended, along with celebrated black nationalists and revolutionaries. Delegates with more moderate position also attended. However, whites were not invited. No white speakers whose views were sympathetic to the movement; not even white reporters. This exclusion caused groups like the NAACP and the Urban League to skip the event and be critical of the gathering.

Renee Ferguson, a former Chicago local news television reporter and currently the press secretary for U.S. Rep. Bobby Rush (D-IL), attended the convention as a 22-year-old reporter for the Indianapolis News. In an interview with Chicago public radio station WBEZ remarking on the 40th anniversary of the convention in 2012, she spoke about the frenzied nature of the event. “When I got there it was very disorganized, much bigger than anybody had planned for and impossible actually for anybody to see what was happening. The speeches were long and there were a lot of egos and there weren’t many women.”

Ferguson said that the agenda of the convention was framed by a basic question, and was the source of great tension.

“Are black people going to work on the inside with the system, or are they going to have their own and work on the outside? And that was the big argument no matter what else they talked about,” Ferguson said. “That was the underlying intrigue and the most interesting thing for me to document as a young reporter.”

In the end, black nationalists won the day. The prevailing theme of the convention was that African-Americans would seek to create change outside of the system. The agenda included platforms that had support from other liberal factions (elimination of capital punishment, national health insurance), but also included platforms that sought to consolidate political control with the growing number of leaders (community control of schools, busing for school integration). Perhaps the biggest message of the convention, however, was that “White politics had failed Black people”. And a new group of leaders set out to implement that vision.

Coalition Builders

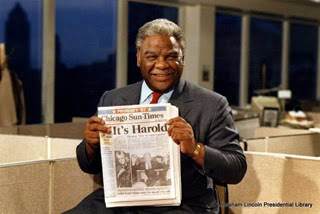

Chicago Mayor Harold Washington, the day after winning the election in 1983. Source: Illinois Historic Preservation Agency.

As a state representative at the time representing Illinois’ 26th legislative district, Harold Washington would’ve been eligible to serve as a delegate to the Black National Political Convention. Whether he attended is uncertain. But it is clear that he adopted a coalition-building style that served him well as he ascended to the office of Mayor in Chicago.

Born in 1922 and just four years younger than Detroit’s Coleman Young, Harold Washington nevertheless followed a different path to mayor of Chicago. Washington also served in the Army during World War II, building runways for long-range bombers in the North Pacific. Upon his return from service he graduated from Roosevelt College in Chicago in 1949, and from Northwestern University Law School in 1952. Washington immediately became immersed in local Chicago politics after law school, working for 3rd Ward Alderman and former Olympic athlete Ralph Metcalfe. While working with Metcalfe Washington became intimately familiar with Chicago’s brand of Machine politics — a spoils system, patronage, and a personal approach to bringing out the vote on Election Day.

Contrary to Young’s experience in Detroit, African-Americans in Chicago experienced a fair amount of political enfranchisement. In many respects, African-Americans were just one part of the ethnic milieu that made up Chicago’s political landscape, like the Germans, Poles, Italians and Irish. The foundation of Chicago’s political machine was its ability to meet the specific needs of those who could be convinced to depend on them, and convincing as many people to depend on them as they could. The Machine’s success meant that it could not ignore or exclude potential votes, wherever they came from, and that included the African-American community. The Machine’s strength was derived from its network of precinct captains, committeemen and elected officials that would convene regularly to discuss its political platform, slate of candidates vote targets and distribution of benefits. Washington received a sound political education in coalition building through his work in Chicago’s Machine.

Washington was elected into the Illinois House of Representatives in 1965 and to the U.S. Congress in 1980. Over the years, he developed a reputation of independence from the Chicago Democratic Party leadership, often becoming an unreliable member of the Machine’s state legislative contingent. As a State Senator Washington was one of a group of independent black Democrats who partnered with white liberal Democrats and moderate Republicans to push forward the Illinois Human Rights Act of 1980. His ascension to Congress later that year, defeating Machine loyalist Bennett Stewart, further alienated him from the Machine.

This effort afforded Washington a unique political perspective. He enjoyed strong independent support from his African-American base, largely developed apart from the Machine. He had strong connections with members of Chicago’s “lakefront progressive” community, which had a fairly large contingent in the city’s Hyde Park community, where Washington also lived. It was likely evident to Washington and others that this pairing provided him a wider base than other black elected officials who rose through the ranks and focused solely on serving the needs of their African-American constituents. Furthermore, Washington likely realized that the Hyde Park progressive community’s networks with other progressives, particularly on the North Side, opened up opportunities for offices beyond Congress.

Washington rode the wave of his unique coalition into mayoral politics in 1983. Bolstered by support from his African-American base and reform-minded white progressives, Washington won against Republican Bernard Epton that November. Once elected, however, he was confronted with a solid bloc of 29 aldermen (out of 50) firmly wedded to the “Democratic Organization” structure that had survived for so long in Chicago. The bloc led a four-year period of legislative gridlock in Chicago known as Council Wars — the bloc assumed control of all Council committees, allowing it to set the legislative agenda; the bloc voted down virtually all of the mayor’s appointments; the bloc fought bitterly with Washington’s supporters on budget and appropriations.

Despite the challenges, however, Washington’s coalition held firm. Federal lawsuits led by Washington allies challenged Chicago’s ward redistricting following the 1980 Census. At the time, Chicago’s population included approximately 40 percent white and black residents, and 15 percent with an Hispanic background. However, Washington supporters argued that wards were gerrymandered to maximize the number of white aldermen in the racially polarized city — at the time of Washington’s election as mayor there were 33 white, 16 black and one Hispanic aldermen. Federal courts ruled in favor of Washington’s supporters in 1986, causing a redrawing of seven wards and special elections. Washington supporters won four elections, creating a 25-25 split in the City Council and effectively giving the mayor control of the Council through his ability to cast a deciding vote. Unfortunately, Washington’s control was short-lived. He died of a massive heart attack on November 25, 1987, just months after his defeat of the obstructionist bloc.

Whereas Harold Washington’s political acumen made him a coalition builder, Baltimore mayor Kurt Schmoke’s stellar athletic and academic pedigree, wonky sensibility and personable nature drew coalitions toward him.

Schmoke attended the prestigious Baltimore City College for high school, where he excelled in football and lacrosse. He entered Yale University in 1967, where he played quarterback for the freshman team and developed into an undergraduate student leader. After graduating from Yale with a degree in history in 1971, Schmoke studied as a Rhodes Scholar at Oxford University and graduated from Harvard Law School in 1976.

Schmoke’s first electoral victory was as Baltimore State’s Attorney in 1982. He defeated William Swisher in a surprise landslide, running a race-neutral campaign against the law-and-order, and (according to some) racially insensitive incumbent. Schmoke was technically not Baltimore’s first black mayor; that title goes to Clarence “Du” Burns, who was elevated to mayor after the election of the previous mayor, William Donald Schaefer, as Maryland’s governor. But Schmoke inherited much of Schaefer’s progressive and business establishment, as they saw him as the one who could articulate their agenda in a largely black city. Schmoke challenged Burns in 1987 and won narrowly. Recalling Schmoke’s victory for an article in Baltimore’s City Paper, City Council member Bill Cunningham said it was a “new-day-is-dawning thing.” In the same article, the Rev. Arnold Howard of Enon Baptist Church said, “We were looking for someone to encompass our hopes for the future, someone who would validate our own journey. He went into office with all that on him. He was the new savior. He was the one who would fulfill our dreams.”

In the end, however, despite being twice re-elected, Schmoke’s analytical approach to leadership alienated coalitions who thought they were getting something else. He developed a reputation for establishing bold policy goals that were difficult to build consensus around — improving adult literacy, drug decriminalization — and put in place department heads who brought the same policy wonk approach to their work that he did. The business establishment and African-American community alike thought they were electing a dynamic “mover and shaker” who could energize them as they pushed toward new heights. But Schmoke was perhaps more manager and caretaker than mover. As a result he left office in 1999, deciding not to seek a fourth term, with a frayed coalition: a business community slightly betrayed, and an African-American community slightly disillusioned.

Trans-Racial Appealists

With the start of the 1990’s a new type of black political figure began to emerge. Gains made through increased access to education and job opportunities were putting more African-Americans in previously unattainable positions, and allowing them to pursue previously unattainable avenues. Wellington Webb, the first black mayor of Denver, fits this bill.

Webb was born in 1941 in Chicago and arrived in the Mile High City at age 11. In his autobiography, he chronicles a difficult childhood; his mother had a drinking problem and he ended up being raised by his grandmother, and he had academic difficulties at Denver’s Manual High School. But Webb fought through his family problems and personal demons. He attended and graduated from Northeastern Junior College in Colorado in 1960, and obtained his bachelor’s degree from Colorado State College in 1964. He was introduced to politics by his grandmother, who was a Democratic Party district committeewoman in Denver. Webb wanted to become a teacher, but found it difficult to obtain a position in Denver’s public schools, and thought local political involvement in some of the federal “War on Poverty” programs of the late 1960’s might help. He transitioned from working in a potato chip factory to working in city government, and later obtained a master’s degree from the University of Northern Colorado in 1971.

Webb developed a reputation as a numbers-cruncher and policy wonk in city government, and was pulled into politics rather than pushed into it by any sense of bitterness. He was elected to the Colorado House of Representatives in 1972 and represented the Northeast Denver neighborhood he grew up in. In 1977 he was appointed by President Jimmy Carter to serve as regional director of the U.S. Department of Health, Education and Welfare, and in 1981 he was appointed by Colorado Governor Richard Lamm to be executive director of the state Department of Regulatory Agencies. Webb held that position until 1987, when he ran and won in the election to become Denver’s city auditor.

Webb’s political ascendance through the ‘70s and ‘80s certainly put him on a path to consider pursuing citywide and even statewide positions, but it was unclear whether an African-American in a city with a small minority population, in a state with a small minority population, could be competitive. He did not start with a built-in large political base like Young or Washington; nor did he have to ability to strengthen a base through coalition building the way Washington did. His only strategy, should he pursue another office, was to make a trans-racial appeal that would highlight his experience, skills and vision.

Webb entered the campaign in late 1990. Three leading candidates emerged: Webb, Denver District Attorney Norm Early (also African-American), and Republican lawyer Don Bain. Webb carried out his “Sneaker Campaign”, going door-to-door in virtually all of Denver’s neighborhoods while preaching a message of competency. He surprised everyone by forcing a runoff with Early in the May 1991 primary, finishing with 30 percent of all votes to Early’s 40 percent. Webb was able to consolidate the support from other candidates with a law-and-order platform prior to the general election against Early in June 1991. Webb won with 57 percent of the vote.

Sacramento Mayor Kevin Johnson. Source: gbmnews.com

Even during his playing days Johnson maintained strong roots with his native Sacramento. He established the Kevin Johnson Corporation, which focused on real estate development and business acquisitions, and the St. HOPE nonprofit organization as an after-school program in the Oak Park neighborhood he grew up in. After his retirement from basketball in 2000, he broadened St. HOPE to include charter schools and nonprofit development in Sacramento. Today, St. HOPE is a network of four charter schools in Sacramento, and a development company with more than a dozen new construction and renovation projects in Sacramento.

Johnson had intimated his political ambitions for years, but finally announced his run for mayor in 2008. Race was hardly a factor in the race; indeed, Johnson was viewed as a decorated favorite son of California’s capital city. Johnson received numerous endorsements from Sacramento’s business and political establishment, and was the highest vote getter in the nonpartisan election that June. He forced a runoff against two-time incumbent mayor Heather Fargo, and soundly defeated her in November.

Johnson has parlayed his athletic, corporate and nonprofit success well in the government sector. He has been a staunch supporter of charter schools, along with his wife Michelle Rhee, the former chancellor of the Washington, DC Public Schools. He was actively involved in keeping the NBA’s Sacramento Kings basketball team from fleeing the city, orchestrating the team’s sale to a group of local investors. He easily won reelection in 2012, and in April 2014 was elected as president of the U.S. Conference of Mayors.

There are other black mayors who fit the trans-racial appeal profile, but are not the first black mayors of their respective cities. Kasim Reed of Atlanta, Michael Nutter of Philadelphia, and Cory Booker of Newark each brought impressive academic credentials, strong corporate backgrounds and youthful passion to their positions as mayor, distinguishing them from their predecessors. Reed interned for U.S. Rep. Joseph Kennedy II before earning his juris doctorate from Howard University, and became a partner at a law firm prior to entering politics. Nutter earned a business degree from the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania. Booker earned his bachelor’s and masters degrees from Stanford, earned a Rhodes Scholarship to attend the University of Oxford, and earned his juris doctorate from Yale.

Because of their academic and corporate credentials, Reed, Nutter and Booker are as comfortable in corporate boardrooms as they are in churches or community centers. Each has forged partnerships with political opponents, and adopted a pragmatic bipartisan approach to governing cities. Each has focused on effective service delivery rather than empowerment or redistributive policies. Booker’s success as mayor of New Jersey’s largest city propelled him to his current position as New Jersey’s junior U.S. Senator through special election in 2013.

The Power of Perception

Detroit, Cleveland, Newark, Chicago, Denver, Baltimore and Sacramento occupy different positions on the success spectrum of American cities. Of these five Chicago would certainly occupy the highest perch. Chicago clearly is a global city — a world financial center, the home of a dozen Fortune 500 companies and the critical link in the nation’s rail and air transportation network. The Windy City has extensive economic connections throughout the world. Indeed, world-class architecture firms based in Chicago are designing the gleaming skyscrapers sprouting everywhere in China’s large cities. Denver would rest in a position not far behind Chicago. Denver has become the capital of the Great Plains and Mountain West, a mid-continent transportation hub that built its wealth on its access to mineral resources in the Rocky Mountains. Sacramento would likely occupy a position behind Denver. Sacramento’s growth has been more recent than the others, and it still sits in the shadows of much larger California metropolises. But as the capital of our nation’s largest and most influential state, it has heft.

Baltimore, Cleveland and Newark would occupy another place on the spectrum. All are well known for enduring the storm of industrial decline, and in Cleveland’s case, fiscal insolvency. They’re slowly recovering from a nadir reached perhaps a decade or two ago and have made small steps toward improvement. They’ve worked hard to revitalize their cores — Newark has leaned on its financial services sector to turn the tide, while Baltimore and Cleveland have relied on their assets in education, health care services, and biomedical and biotech research. However, all are far from being complete success stories.

Then there is Detroit.

Each city has had African-Americans serve in the city’s highest office. Chicago’s Harold Washington endured tough times as mayor of Chicago, but he built a lasting coalition that allowed him to prevail. Denver’s Wellington Webb learned to adapt in a pluralistic environment and raised the profile of a Western city. Cleveland, Newark and Detroit each elected first black mayors during the turbulent post-Civil Rights era and paid a steep social price for doing so. Cleveland and Newark began their turnaround some years ago; perhaps Detroit’s, with its recent bankruptcy filing, has just begun.

If anyone doubts the impact of electing an African-American mayor during the racially tumultuous late ‘60s-early ‘70s era, examine the general perceptions that formed of the cities during that period and have endured ever since. Newark and Detroit, already tainted by the aftermath of urban riots, were effectively shunned by white residents after the elections of their first black mayors. Cleveland may have been headed down the same path after the election of Carl Stokes in 1967. But Stokes chose not to run for a third two-year term as mayor, leaving a wide open field. Stokes was followed by three consecutive white mayors — Ralph J. Perk, Dennis Kucinich and George Voinovich — before the election of the city’s second black mayor, Michael White, in 1990. Atlanta touted itself as the “City too busy to hate” in the ‘70s, but Maynard Jackson’s 1973 election coincided with rapid white flight out of the city, at the same time that Sun Belt migration from the north was strengthening the suburban base. In Washington, DC, black political empowerment there was often wrapped up in the controversy of federal political representation for the District. Mayors in the District were federally appointed until Walter Washington was elected mayor in 1975.

Perhaps the best way to view perceptions of cities that elected “first black mayors” during the Black Power Era is to examine the fortunes of Detroit and Philadelphia during and after this period. Entering the 1970’s the Motor City and the City of Brotherly Love had similar populations (about 1.5 million people in Detroit, 1.9 million in Philadelphia), with a similar geography (about 140 square miles) and similar demographics (approximately a 60/40 split between whites and blacks). As noted, Coleman Young was elected mayor of Detroit in 1973, narrowly winning against Police Commissioner John Nichols. It was clear that Nichols’ candidacy was an effort by his constituency to restore order to a city during a difficult time. Meanwhile, another police commissioner, Frank Rizzo, assumed power as mayor of Philadelphia in 1971. As mayor Rizzo was regarded as having a strained relationship with the city’s African-American community. Rizzo’s “law-and-order” tactics were viewed positively by his white ethnic base and have been credited by some for keeping Philadelphia from suffering the same fate as other cities. Could the Nichols campaign have been modeled after the successful Rizzo election two years earlier?

Possibly. Yet it is instructive to view the difference in perceptions of both cities since that time. Philadelphia was certainly hit hard by the decline of the nation’s manufacturing sector. Philly had substantial losses in the shipbuilding, oil refining and food processing industries over the decades, losing thousands of jobs as a result. Yet did Philly endure what was in effect a boycott of the city by white residents? Troubled North and West Philadelphia are well known, but did their troubles define the entire city? I think many people could imagine a real-life “Rocky Balboa” coming from Philadelphia in the ‘70s and ‘80s, but far fewer could imagine a similar character coming from Detroit.

Philadelphia’s national perception took a tumble over the last 40 years, but the city has fought back hard to rebuild itself as a premier city with a strong economic foundation in education, health care and financial services. Detroit, however, continued on a descent no other city endured. High crime rates, racial tensions, dilapidated abandoned buildings in a desolate post-industrial landscape — all defined Detroit then and continue to define it today.

Between 1970 and 2010, Philadelphia’s population dropped by 22 percent, from 1.9 million to 1.5 million. The decline was largely driven by a substantial loss of its non-Hispanic white population over the period, which declined by 56 percent. Over the same period, Detroit’s population dropped by 53 percent, from 1.5 million to just over 700,000. Its decline too was largely driven by a loss of its non-Hispanic white population, which dropped by 93 percent. Ninety-three percent.

Something happened that kept a base or core of white residents in Philadelphia. Something happened in Detroit that led to their virtual disappearance.

Cities that elected their first black mayors during the Black Power Era deeply suffered in national perception because of the gamut of social challenges they had at the time, and found it difficult to stabilize poor economies or for revitalization to gain traction. But they suffered far worse than other cities because they were in effect shunned. They suffered from the greatest increases in crime. They experienced the largest declines in school quality and performance. They witnessed the steepest drops in property values. They had the widest divides between police and community. They had the highest numbers of white middle-class residents departing for the suburbs. Newark was shunned. Gary was shunned. Detroit was shunned. Maybe Cleveland, Los Angeles, or Cincinnati, or Dayton did not suffer the same fate because African-American populations there did not approach parity with whites, who were eventually able to “reclaim” the city’s highest office. In the end, however, select cities paid a price for the election of black mayors during this time, a price not paid by cities that elected black mayors after them, or not at all.

Another Transition

Detroit Mayor Mike Duggan on election night in 2013. Source: wikipedia.org

The new mayor said he would focus on operations — removing blight, snowplowing streets, repairing lights, making sure buses run safely and on time. The mayor suggested he would move into Manoogian Mansion, the palatial mayoral residence on the Detroit River that was deeded to the city in the 1960’s. As far as the focus on operations goes, he really has little choice in the matter. The State of Michigan-appointed emergency manager Kevyn Orr, brought in with exceptionally broad powers to resolve the city’s financial mess and currently leading the Motor City’s largest-ever municipal bankruptcy, has a lock on policy decisions right now. Mayor Duggan says his focus is to “return the city to elected leadership on October 1,” the day that Orr’s 18-month appointment from the state ends.

And with that, Mike Duggan became the first white mayor of Detroit since 1973, mayor of a city with a population that is 83% African-American. This most recent election, most observers believe, is a venture into the unknown, and is as much an experiment as Detroit’s bankruptcy itself. An era of African-American political leadership has ended in Detroit, but no one is certain of what the next era might be.

Perhaps the bankruptcy, the election of a white mayor and the growing urban pioneer spirit that is visible in parts of the city means that the shunning of Detroit has ended.

This post originally appeared on August 10th, 2014 in <ahref=”http://cornersideyard.blogspot.com/”>Corner Side Yard.