This post originally appeared in New Geography on June 7, 2013.

Suburbs are often unfairly maligned as lacking the qualities that make cities great. But one place that criticism can be fair is in the area of sacred space. There most certainly is sacred space in the suburbs, but usually less of it than in the city both quantitatively and qualitatively. In fact, the comparative lack of sacred space is one of the distinguishing characteristics of the suburb that makes it “sub” urban, that is, in a sense lesser than the city.

Lewis Mumford put it this way:

Behind the wall of the city life rested on a common foundation, set as deep as the universe itself: the city was nothing less than the home of a powerful god. The architectural and sculptural symbols that made this fact visible lifted the city far above the village or country town….To be a resident of the city was to have a place in man’s true home, the great cosmos itself.

Mumford was onto something here in positing how great temples and such distinguished the city as unique.

What Is Sacred Space?

Mumford also hints at what makes something truly sacred space. We should clearly distinguish between what is merely public space and truly sacred space. The key to sacred space is the linkage to the transcendent. That is, sacred space connects us to something beyond or bigger than our surroundings, our present existence, and even ourselves.

Here are three ways sacred space can do that. It can:

- Connect us to a larger spiritual or religious reality, as in our Mumford example. This is the most obvious case.

- Serve as a locus or repository of the culture and traditions of a people.

- Be a temporal connection between the present and the past and/or the future.

As one example, consider the Indiana World War Memorial in downtown Indianapolis.

Also note the use of neoclassicism. The use of neoclassical architecture anchors Indianapolis and Indiana firmly within the 2,500 year history of Western Civilization, as a link in a chain of peoples connected by shared, timeless values and extending backwards and forward throughout time, thus achieving a sort of immortality. This building is a statement of the permanence of this community, its people, and their values.

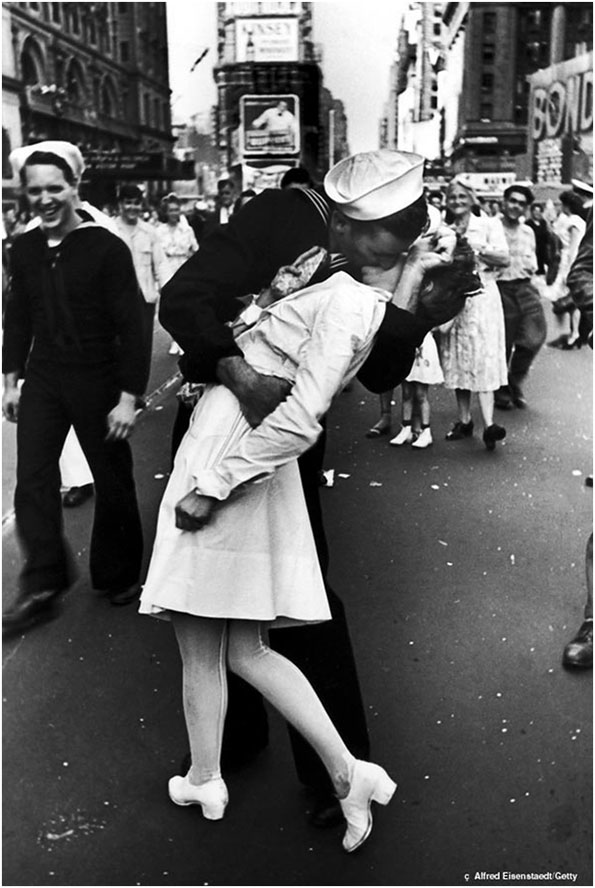

We can also think of a radically different space such as Times Square, and how it has played host to so many civic celebrations and traditions over the years such that it has become not just a local but a national repository of our culture. The ball dropping on New Year’s Eve is an obvious example. But consider also this iconic photo.

How Suburbs Are Comparatively Lacking in Sacred Space

Let’s apply the definition of sacred space to the suburbs. Yes, suburbs do have war memorials and culture and traditions and churches, but in general these are qualitatively different from what is found in the city core. Here are three reasons why.

1. Suburban traditions and spaces are often ephemeral and generational. When I was in high school, everybody liked to go to a place called Down Home Pizza in Corydon on the weekends. And that was something kids from every high school in the area did, not just those from mine. Today that place is long gone. And the kids are doing something else, whatever that may be. In fact, it’s amazing how many of the places and traditions from my high school days are already gone after only 25 years because of physical and economic changes in the community such as restaurants and stores going out of business.

This happens in the city too, like when the department stores went under, taking their white-gloved tea rituals and the like with them. But to a much greater extent than the city, suburbs rely on commercial establishments as focal points of shared experience, and by their very nature those tend to come and go. And suburbs have not to nearly as a great a degree established truly trans-generation rituals and spaces.

2. Lack of transcendent scale. This is also something Mumford hints at. The “human scale” is a big buzzword in urbanism today. Contrary to what many say, the suburbs actually do a pretty good job of the human scale, especially from an automobile era perspective. But a unique essence of urbanity and often of transcendent experience itself is what we might call the “anti-human scale.” British writer Will Wiles put it this way:

The “human scale” only tells part of the story of the city — after all, this can be found in villages and small towns. All cities need sublimity, a touch of holy terror, a defiance of human scale that asserts connection to the greater urban whole.

The sheer scale of something like the Indiana War Memorial, which is a very imposing structure inside and out, renders it qualitatively different that your average small scale suburban memorial. This is true not just physically but also in terms of the humanity represented. That memorial stands for an entire state, not just a single town. Which is the same reason there may be more suburban school kids who have visited their state capital or the US Capitol than their local village hall. There’s a reason the US Capitol and Lincoln Memorial and such have such powerful resonance. They represent an entire nation and a vast sea of humanity. Cities also participate in this scale effect.

3. Low quality religious architecture. When it comes to the most obvious category of sacred space, the religious building, the suburbs also fall flat. That’s because Protestant Christianity, the largest suburban religious strain, has itself become unmoored from the transcendent. This is clear, for example, from the rise of what has been dubbed “Moralistic Therapeutic Deism” as a dominant worldview, especially among the young.

The average suburban megachurch is an architectural horror show. The best of them generally rise to the level of an upscale corporate conference center. The worst are like “That 70’s High School”.

Someone once said that all sin results from failing to believe one of the “4 G’s” about God, namely, God is great, God is good, God is gracious, and God is glorious. Applying that to religious life generally, in modern Evangelical churches, God may be very good and gracious, but He’s doesn’t seem all that great, and He’s certainly not very glorious. This is religion that can inspire good works, but not great ones. There’s no trace of the overwhelming glory of God in nearly any of these structures. There’s no longer a faith like the Lutheranism of Johann Sebastian Bach that can inspire the greatest works of human artistic achievement. Because modern suburban church architecture is so poor and so disposable, it diminishes the impact of sacredness in the space.

The recent stories about the sale of Orange County’s Crystal Cathedral, designed by Philip Johnson, brings to mind an exception that proves the rule.

So sacred space is one area where the suburbs really are deficient versus the city. But how important is this? Metropolitan areas today are mosaics. In an ever more complex and competitive global economy, every part of a region, city and suburb, needs to know its role on the team and bring it’s A-game. Just as there’s no need for every job to be located downtown, there’s no need for every major piece of sacred space in a region to be replicated in every suburb. Downtown does just nicely. However, this is one reason that while economically the core may no longer dominate a region, a healthy center still plays a key role in overall regional vitality. That’s because it remains home to things like the major pieces of sacred space such as war memorials and cathedrals that bind a region together and give it civilizational permanence, meaning, and purpose beyond the mundane.

This article was adapted from remarks at the No Place Like Home conference on June 3, 2013 in Anaheim, CA.

I’m a classics scholar (and I enjoy neoclassicism quite a bit), but the bits about “shared, timeless values” are a gigantic misrepresentation of what antiquity and Western Civilization are.

“Unsurprisingly it was the Catholic Church that bought it. Unlike Protestantism, Catholicism has always had a theology of place. And they’ve always used architecture and art as a way of telling the story of the gospel. Though obviously not in this case, they’ve also used Gothic sort of like neoclassical architecture as a way creating a sense of permanence and linkage to an everlasting, eternal church.”

I’m curious whether you can point to any examples of suburban Catholic churches that were built after 1965 that fit this mold. They exist, but are few and far between. It seems to me that Catholic church architecture has come at least as unmoored as Protestant church architecture in the last half century (and probably moreso given what you point out about Catholic theology). I don’t think it’s a coincidence that so many Catholics prefer to have downtown or near-downtown weddings at St. John, St. Mary, SS. Peter & Paul Cathedral, and Sacred Heart rather than in the suburban parishes where they grew up. I think it was Pat Conroy who derided the typical modern Catholic church buildings as “toadstools” (think St. Matthew or St. Barnabas in the suburban parts of Indianapolis). Obviously, none of this is to disagree with your overall point.

John, I actually have a post from a guest writer tomorrow on modernism and the Catholic Church that will talk a bit about this. My understanding is that in recent times there’s been more of a shift back to traditional Catholic architecture, albeit not easy to discern as there aren’t a huge number of Catholic churches being built this day vs. Protestant ones.

Thanks. I’ll be interested to read that piece.

John, it’s not a parish church, but one of my favorite modern suburban churches is the Norbertines’ Daylesford Abbey in Paoli PA. (Google it and look at the photo gallery on their website.)

It is rare because it’s a 1966 Brutalist structure that is beautiful inside and out. Its solid construction gives it wonderful acoustics. Because it’s the seat of an order, it has a little more of a sense of permanence.

There are of course Catholic (and Anglican) churches that have distinctly modern architectural languages that still at least attampt to instill this sense of awe…and even tradition.

Chris, I agree that the Daylesford Abbey works. It’s significant that it was built in 1966, just a year after the Second Vatican Council concluded. While the materials and the spare nature of the sanctuary are of their time, the shape of the building is fairly traditional. Compare and contrast that building to the “auditorium-style,” for lack of a better term, Catholic churches that sprung up in the 1970s, which were influenced both by the design trends of the time and by the effort of Vatican II to make the Church more accessible to the laity. I’m hardly a “conservative” or “traditionalist” Catholic. I generally think Vatican II did more good than harm. But I can’t think of anyone, from the hardcore Latin Mass devotees to the going-through-the-motions cultural Catholics, who doesn’t prefer pre-Vatican II church architecture.

As one might imagine, a couple of the small churches of Columbus Indiana are inspiring Protestant places: Harry Weese’s First Baptist and Eero Saarinen’s North Christian. Like Daylesford, they are in relatively traditional church form and definitely “of” the mid 1960s in their spare nature.

They are not suburban, except that they were both built at the edge of town in their day.

First Baptist is a fairly traditional building, but North Christian Church is a hexagon.

Anyone interested in this topic should read “Ugly as Sin” by Michael Rose.

http://www.amazon.com/Ugly-as-Sin-Michael-Rose/dp/1933184442/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1407860720&sr=1-1&keywords=ugly+as+sin