[ I’ve posted a number of pieces by Pete Saunders here in the past. He’s not just a great analyst generally, he’s particularly great on Detroit. His post laying out nine reasons why Detroit failed has more page views than any other article in Urbanophile history. (The top four posts are all about Detroit, showing the powerful hold that city has on the public consciousness). In his blog, Corner Side Yard, he’s bee revisiting that post to go in depth on each of his nine points. Today I’m pleased to be able to repost his analysis of Detroit’s housing stock, along with that of many other Midwest cities – Aaron. ]

A scene from the Grixdale neighborhood on Detroit’s northeast side. Source: Google Earth.

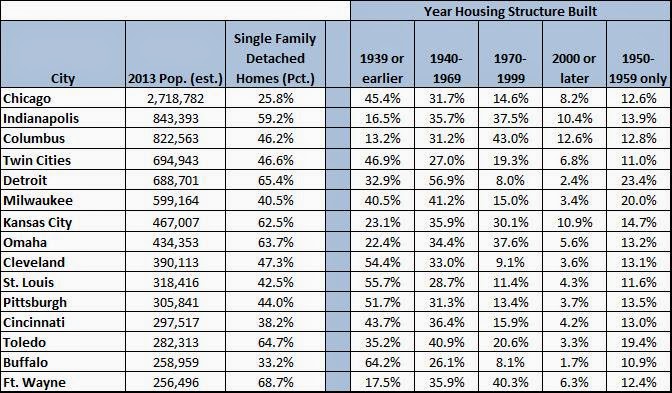

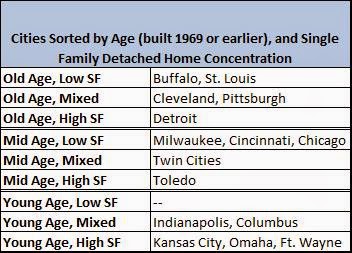

Grouping the cities by population figures from the 2013 U.S. Census population estimates, and housing data from the 2008-2012 American Community Survey, I looked at housing age and single family detached housing data for 15 Midwest/Rust Belt cities with populations above 250,000. One city I typically include in an analysis like this, Louisville, was not included due to a lack of ACS data. Data for the Twin Cities of Minneapolis and St. Paul were aggregated into one (sorry, Minneapolis and St. Paul) because they jointly function as the core city for their region. Here’s the big table with all the data:

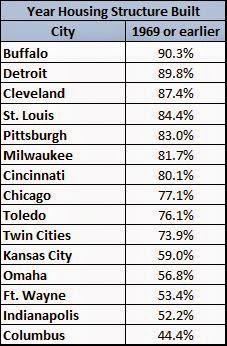

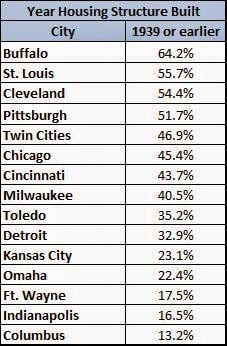

But does it really? If you look at the Census’ earliest category for age of structure, 1939 or earlier, Detroit drops considerably on the list:

Next, let’s look at how the cities rank in terms of their concentrations of single family detached homes:

Clearly, most observers believe Detroit has more in common with Buffalo, Cleveland and Pittsburgh than with Ft. Wayne, Kansas City and Indianapolis. What happened to Detroit’s housing stock that gave it such an odd profile?

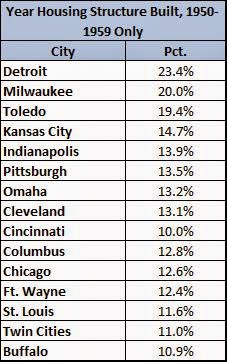

To understand, let’s pull out a specific category on the age of structure table, the 1950-1959 category:

How did Detroit get this way? Housing demolition likely had some role in a city that lost so much. Detroit likely lost older single family homes and multifamily buildings over the last few decades, leading to skewed numbers. The same is also true of Indianapolis, Kansas City and Columbus, cities that annexed large undeveloped areas after 1970 and built new housing there. Keep in mind, though, that Milwaukee and Toledo, Detroit’s comparables, may not have had the same level of demolition loss that Detroit had, yet they still match the Motor City well.

That leads me to believe that a concentration of housing development at a unique time is a crucial piece in understanding Detroit’s housing stock.

Here’s another way of looking at this. I grouped the cities by age and single family home concentration and came up with interesting groupings:

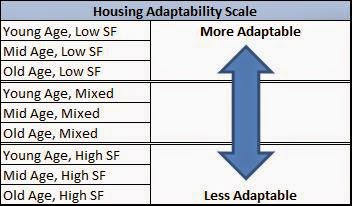

Finally, let’s consider housing adaptability as part of the housing stock analysis. Chicago, the region’s largest city and lone “global city” member of the group, comfortably rests in the middle of all tables except for the single family detached table, where it shows the lowest concentration of single family homes. My guess is that Chicago’s continued desirability means more newer housing has been built, and that its lower single family housing numbers mean that other housing types (lofts, condos and the ubiquitous 2-flat and 3-flat) created a more flexible and adaptable housing development landscape.

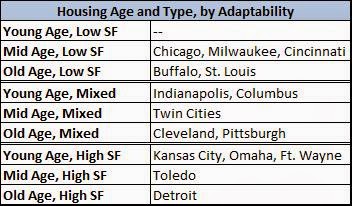

Assuming that younger structures are more often suitable to renovation for adaptability, moderately old structures require more intense rehabs, and older types are more often subject to demolition and rebuilding, I reorganized the previous table in terms of housing adaptability:

The more I study Detroit, the more I see the seeds of a similar downfall in other cities nationwide.

This post originally appeared in Corner Side Yard on July 6, 2014.

Very interesting piece that I don’t think has been covered elsewhere. One critique is that Chicago has experienced more residential new construction than Detroit which would skew the pre-1969 %. There shouldn’t be an implication in this analysis that older means more dense and urban, though that is usually the case.

Looking at population growth, what it comes down to is that Chicago grew as a result of the industrial revolution pre-1900’s and Detroit grew as a result of the automotive industry post-1920’s, same could be said for Toledo and Ft. Wayne.

I would say the predominate housing type outside of the historical boundaries of the Grand Blvd. and Outer Dr. would be the bungalow. Some where constructed solidly, other’s were done very cheaply by tract subdividers and are now being demolished (Brightmoor). The problem with urbanism in Detroit is that there isn’t that much of it to begin with, and why live in Detroit when you can get that same bungalow in Redford Twp. or elsewhere minus the social and economic issues?

Great job in comparing potential by housing type and density. This is a unique analysis with hope that it can drive policy.

One interesting question comes from a California perspective. It is easy to disparage the Detroit bungalow…but we are seeing a problem with the ubiquitous 1950s-1970s California rancher. These generally cheaply building houses are NOT aging well!!!

As undesirable as midrange Chicago suburbs, for example, can be….compared to the lesser suburbs of California, the Chicago vernacular looks downright attractive!

Of course…California is still experiencing serious population and price pressure, so there is almost zero abandonment (there was a spike of problems during the housing crash, but other than that)

Brian, the term bungalow means very different things in different places. Chicago bungalows are a pre-War type of housing stock and reflect the generally high quality standards of the era. Detroit’s are post-War worker cottages. If you read the history of the era, there was a massive pent-up demand for housing and limited building materials available, hence the Levittown type of development.

Interesting to hear the challenges you are seeing with the California ranch.

Pretty simplistic to lump houses by age and size alone. Are newer homes by definition automatically more “adaptable”?

The home itself tells a small part of the story. What is the street grid like? Are there sidewalks? Are there mixes of densities and uses built over time (like Pittsburgh’s Shadyside & Squirrel Hill)Is there transit? Have industrial nearby lots been reused & are they open to reuse? Do local laws allow for converting large homes to multi family?

Detroit built a perfect storm of cheap generic worker housing in generic neighborhoods.

Pittsburgh’s Bloomfield, Lawrenceville & The South Side are high quality neighborhoods made up of mostly low quality housing.

I asked my grandfather why he chose to move his family out of a cheap bungalow in the Brightmoor neighborhood on the city’s far west side and I was expecting him to say because of increasing crime or schools as this was around the time of the Milliken v Bradley school busing case. Though the neighborhood was changing, his motives weren’t about issues like crime and schools that are so prevalent when discussion Detroit today, or post-1980’s “Just Say No”. It was something as simple as just wanting a nicer, bigger house, which Farmington offered. That’s it, sometimes people just want more bedrooms and thinking about it now for myself, that really is one of the huge factors in choosing where to live, the housing product.

Williamsburg Brooklyn is also a good example of a highly desirable neighborhood with a pretty low quality stock of mostly wood row houses.

Huge difference was the conversion of neighboring warehouse & industrial buildings. Ohio City & Tremont in Cleveland also have that character.

“that really is one of the huge factors in choosing where to live, the housing product.”

If most of the other factors, walkability, transit, safety, shopping work well- one can always gradually upgrade the housing. Lawrenceville, South Side & Williamsburg, Brooklyn are good examples of this. Same process is happening in NYC’s East Village.

I really worry about the fate of these first post-war Cape Cod style suburbs (veteran villages?). They’re old enough to have all the problems of old houses, but not old enough to have the construction quality or the design and charm you find in pre-war housing. They also tend to be laid out in a sort of urban-lite arrangement, whether in completely new developments or build outs of pre-depression subdivisions that were stillborn. They’re not urban enough to compete even with streetcar suburbs, but at the same time they’re too dense to really offer a compelling suburban product.

There’s no shortage of these kinds of houses around Cincinnati either, though certainly not to the extent you see in Detroit. Many of them are pretty dowdy looking these days, and even some of the first ring suburbs made up mostly of these sorts of houses (Fairfax, Golf Manor, Deer Park) are at least stable but not particularly desirable for their housing. I don’t see them really getting markedly better over time, and in the rougher neighborhoods these sorts of houses go to crap really fast.

@ John Morris

But it’s much easier and timelier to upgrade housing product in the suburbs than finding a comparable, affordable product in an urban area. Goes back to missing middle housing we stopped building after WWII.

Can’t fully argue with that. Although, improving housing alone without improving other issues usually doesn’t work.

Detroit itself has lost many amazing mansions. My Grandmother years ago left a fantastic Victorian in Boston’s Dorchester due to safety, walkability issues.

Friendship & Highland Park in Pittsburgh are now probably fully reviving because the surrounding areas have improved. Neither alone could support great shopping districts.

Jane Jacobs quote from Death & Life- page 33-34

“Meanwhile, in the Elm Hill Avenue section of Roxbury, a part of inner Boston that is suburban in superficial character, street assaults and the ever-present possibility of more street assaults with no kibitzers to protect the victims, induce prudent people to stay off the sidewalks at night. Not surprisingly, for this and other reasons that are related (dispiritedness and dullness), most of Roxbury has run down. It has become a place to leave.”

Houses built between 1950 and 1980 lack the architectural significance and attention to detail of older houses, and the modern amenities of newer houses. As a result, they’re going to be hard sells.

The average price of housing in the Pittsburgh metropolitan area continues to gradually increase, but that’s because the glut of suburban tract housing built between 1950 and 1980 remains flat in value while renovated old houses in the city fetch top dollar, and new houses can’t be built fast enough to keep up with demand either in the city or the suburbs.

As poor people continue to get priced out of the city, they’ll end up living in suburbs that are overloaded with these middle-aged houses that haven’t aged well.

But, most Pittsburgh suburbs also lack the walkability, transit and shopping advantages the city has. These are often poor quality houses in poor quality places.

The contrast the old Lower Hill to Homewood. By most definitions- the lower hill had a much poorer & overcrowded housing stock but clearly had many aspects of a high quality neighborhood like a thriving local business district, culture, churches, walkability, transit & access to downtown.

http://teenie.cmoa.org/interactive/index.html#theme01

Almost certainly- the area would have improved on its own if allowed.

Homewood has (had) many fine large homes mostly on dull long blocks with sparse shopping. It went into a long decline.

I wonder how possible it would be to scale all these cities to the same size as Detroit and see what housing looks like then. The numbers are going to be skewed in some way based on, as the article states, things like annexation.

Hey, Pete, thanks for the inadvertent advertisement of Buffalo’s superior housing stock. Of the cities you studied, only ours is older that Detroit’s. That means that the lush Queen Anne that only a gazillionaire can afford in San Francisco can be owned by a carpenter and a librarian in Buffalo, as ours is.

Architectural eye candy starts at around .58:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lMx6MO1IZCc

And sadly Buffalo shows a great housing stock alone can’t save a city – It’s only one part of how things interact and work.

Which is why at least one Buffalo gem has been picked up and moved to another city.

Pete, Aaron: I recall reading somewhere that Detroit had a large stock of single-family houses even before WW2. Am I remembering right?

If it did they had probably not been very old. The city went through a massive wave of growth 1910- 1950.

It also very quickly went through waves of outward industrial sprawl as factories were replaced by newer large footprint plants further out. Each wave left abandoned belts.

Piquette, the original Ford Model T plant was obsolete in 9 years.

“Completed in 1904 and tiny by modern standards, the small plant measures only 400 by 56 feet with three floors, but was successful enough to outgrow its capacity in only nine years.”

The small Hudson plant was obsolete by 1912.

“The modestly-sized Hudson plant was originally home to the Aerocar company (no not that Aerocar) and was opened to produce Hudsons beginning in 1909. For the next three years Hudsons of the time were built there, but then in 1912 production was moved to a much bigger and more modern plant”

The 3,500,000 Square foot Packard complex closed in 1958

The much larger Highland Park Ford plant closed in the early 70’s after already downsizing.

http://jalopnik.com/5110995/the-ruins-of-detroit-industry-five-former-factories

This pattern of outward growth and abandonment started very early.

Another huge 2,200,000 SF plant, in trouble early was The Russell Industrial Center- probably the only really big complex to undergo sustained reuse.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Russell_Industrial_Center

“Murray’s company began having financial problems during the economic recession in 1924-1925. During that time he formed a merger with C.R. Wilson Body Co., one of Henry Ford’s major suppliers. After the merger, the company’s newly elected president, Allan Sheldon, made a series of costly mistakes; the first was suppling Hupmobile, which was located 400 miles (640 km) from Detroit, which resulted in high transportation costs; next the overproduction of parts in 1924 for the anticipated 1925 sales resulted in the layoffs of factory workers. Next the stock market crash of October 1929, and the Great Depression negatively affected the automobile industry. The Ford plant eventually had to shut down and the Murray Corporation continued to struggle until 1934.

In the 1940, Murray maintained a lucrative printing business, and began manufacturing military supplies, airplane wings and other components of the fighter/bomber planes, and washing machines for Montgomery-Ward. When the war came to an end, expressways opened up the city of Detroit to the surrounding suburbs. This led to suburbanization, and another recession for Murray. He continued manufacturing automotive parts for a short time, but eventually had to close operations.”

Later, printing companies used part of the complex.

New worker housing followed the plants outward.

For whatever interest it carries, it’s worth noting that the majority of the 1950-1959 era homes in Detroit were built in the northwest corner of the city. In fact, the very northwest tip of the city is the only area to have gained population since 1950: http://4.bp.blogspot.com/-jC_IFRpF0N0/UxOD2lBqmkI/AAAAAAAAADw/uIFH5VPXTm0/s1600/Detroit+1950+2010.png .

Of course, if trends continue, even that section will probably be sporting a negative number by 2020 or 2030. It’s also interesting to see the continual population decline in the area of Southwest Detroit popularly known as “Mexicantown”.

Truth is, most of that area has been shedding people overall for decades, with only a few small pockets of occasional growth. However, increased activity on the Vernor commercial corridor has convinced outsiders that the area is thriving, and that image is a big part of Governor Rick Snyder’s push to have more immigrants move to Detroit.

It’s my honest belief that Detroit’s endgame is to have a moderately dense urban core surrounded by an unbelievably vast urban prairie. Some of that unpopulated land will be converted, I believe, to very heavy industry (that, of course, employs few people). Not sure about the rest.

Southern California which also underwent an explosive period of manufacturing sprawl and migration, may be a better comparison to Detroit than most older “Rust Belt” cities.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Compton,_California

“The 1920s saw the opening of the Compton Airport. Compton Junior College was founded and city officials moved to a new City Hall on Alameda Street.On March 10, 1933

…

“Compton grew quickly in the 1950s. One reason for this was Compton was close to Watts, where there was an established community of African Americans. The eastern side of the city was predominately white until the 1970s.”

@Alon, I don’t know the composition of Detroit’s pre-War housing stock. Maybe Pete has the info.

Alon: I don’t know any specific stats, but it’s the academic consensus that Detroit was primarily composed of single-family homes. Certainly, there is tons of photographic evidence of sprawling subdivisions that were built within the city limits before 1940, and I do know that 50,000 single family homes were constructed between 1923-1928. 45% of Detroiters owned their own homes by 1940. By 1960, Metro Detroit’s building stock was 3/4s single-family homes.

Detroiters that rented typically lived in duplexes, old mansions that had been converted into apartments, or relatively modest apartment buildings that were constructed randomly on streets of mostly single-family homes. There was a plan beginning in the 1910s to create a grand urban core along Woodward (the main drag) from downtown to New Center, about 3 miles north. However, that fell through well before completion with the onset of the Great Depression, and little was accomplished after the point.

Places like Hamtrack probably give one a peek at what some of the housing may have been like.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hamtramck,_Michigan

I do see quite a lot of single & two family houses probably pre 1940. But Detroit underwent very early waves of demolition near the core.

What’s left of Poletown seems similar with one and two family homes of an earlier type, more closely packed with no driveways. Guessing these date 1915- 1940.

Also, about 80% of Detroit dwellings are now single-family (with the caveat that this percentage includes attached homes). Which, really, is one of Detroit’s biggest problems. Most people in Detroit aren’t making enough money to maintain single-family homes.

Cleveland neighborhoods like Slavic Village might give a peak at what some of Detroit’s earlier working class housing looked like.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/South_Broadway,_Cleveland

“the neighborhood peaked in the period from 1920s to 1940 and began to decline during migration of the people to the villages, when the city suffered demographic decline during the 1950s and 1960s.”

As someone that has spent of his life in Metro Detroit, great examples of what typical “old Detroit” looked like are the cities of River Rouge, Ecorse, and Dearborn. River Rouge and Ecorse have seen better days, but are mostly intact representations of common working class neighborhoods. Check ’em out on Google Streetview. Throw in some random apartment buildings that look like this: http://wjbk.images.worldnow.com/images/22059866_BG1.jpg, and you’ve got a good visual.

East Dearborn (not the west side) is basically the sort of neighborhood the well-to-do middle class would’ve called home.

Mexicantown in Detroit isn’t a bad example of what peak Detroit looked like, either, though you’d want to stay close to the Vernor corridor to get the most accurate picture.

Oh yes, and I’d be remiss not to mention the west side of Grosse Pointe Park (though not the east). That’s basically a classic Detroit neighborhood, and is in excellent shape.

If you click Poletown images, you get some historic shots.

Mexicantown seems to show a lot of earlier housing stock.

Pre-war housing stock is still predominately detached single family- look in east side neighborhoods Indian Village, West Village, or Boston-Edison or what’s left of Brush Park. For some reason, Detroit pretty much rebuffed townhouse and multifamily housing or it was torn down for urban renewal. It never had rowhouses to the extent that cities like Chicago, Boston or Cincinnati have them. That all goes back to when a city grows.

Forgive me for not following up on the comments, but thanks for the read and critiques.

A few people asked about Detroit’s pre-war housing composition. I haven’t done it yet, but I want to pull the 1960 census data on Detroit, since it’s established now that so much housing construction happened in the ’50s. I’d like to see the age of structure there, if the Census actually collected that data, and if so I’d bet it breaks down housing stock age prior to 1920. When I find it I’ll write it up on my blog.

As far as the look of pre-war Detroit, I think George V. hit the nail on the head. Hamtramck, Grosse Pointe Park, River Rouge, Ecorse and Dearborn all look very much like 1920s-30s Detroit. Predominantly single-family, small lot size, mostly bungalows. Hardly any attached housing, and multifamily restricted to 4-6 unit structures in limited areas. Similar in character to what came after in the ’50s, but probably of much better quality. And surely nothing akin to what was found in larger East Coast cities.

In fact, this leads me to another thought about Detroit. To me Detroit never intended to be a major city in the sense that New York or Chicago, or even St. Louis or Cincinnati, aspired to be. Old Detroit looked much more like midsize Great Lakes cities like Toledo or Grand Rapids or South Bend, and never like much larger cities. I’ve already demonstrated that Detroit and Milwaukee’s growth paralleled each other for decades prior to the explosion of the auto industry; both were the largest cities and ports of entry of similarly modest-sized Midwest states. And I believe Detroit was content to exist at that same scale. If Henry Ford had been born outside of Indianapolis, I suspect Detroit wouldn’t have reached half its peak population in 1950, and wouldn’t have fallen so dramatically over the ensuing 60 years. It’s growth profile would have continued to mimic Milwaukee’s.

In other words, maybe Detroit is undergoing a reversion to its previous — and preferred — development form. It only turns around once the reversion is complete.