Thursday I took a look at my “Cincinnati conundrum,” namely how it’s possible for a city that has the greatest collection of civic assets of any city its size in America to underperform demographically and economically. In that piece I called out the sprawl angle. But today I want to take a different look at it by panning back the lens to see Cincinnati as simply one example of the river city.

There are four major cities laid out on an east-west corridor along the Ohio River: Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, Louisville, and St. Louis (which is not on the Ohio River, but close enough. I’ll leave Memphis and New Orleans out of it for now). All of these are richly endowed with civic assets like Cincinnati is, having far more than their fair share of great things, yet they’ve all been stagnant to slow growing for decades.

This suggests a broader challenge: if urbanity and quality of life are so determinant of economic success, why aren’t these places juggernauts? It’s not that they are failures by any means, but they are long term under-performers.

Over the Rhine, Cincinnati – one example of the spectacular urban assets of these cities

These cities came of age earlier than railroad based cities like Chicago. These are some of the earliest major cities in the region, and they owe their prominence to the era when the river was the major form of transport. They’ve all had a heavy German Catholic influence, hence the legacy of breweries and the importance of private Catholic high schools in these areas even today. They have bridge-oriented transportation traffic patterns and bottlenecks. They’ve got interesting geography with hills and trees and some similar climate patterns.

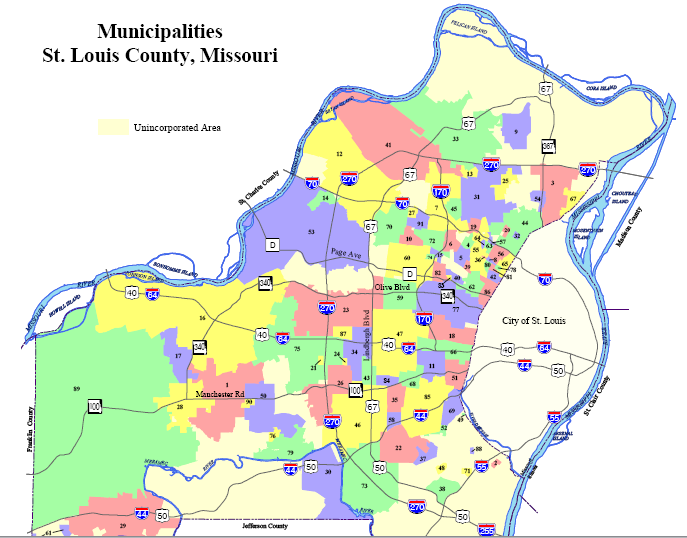

I find it particularly interesting that they have similar political geographies, despite being in four different states. Three of them are multi-state metros, obviously, because the rivers are state borders. But beyond that they all have hyper-fragmented systems of lots of tiny cities and villages that are fiercely independent. Here’s a map of all the municipalities in St. Louis County, for example:

Image via ArchCityHomes

Inside the cities themselves, there are also many well defined, distinct neighborhoods. These are usually small in size compared to what are called neighborhoods in cities like Chicago. Also, there can be deep divisions between the different sides of town. These are very divided cities. Cincinnati has the East Side-West Side divide. Louisville has the East End, the South End, and the West End. And which one you are from is a huge cultural marker. The North and South Sides of Indianapolis are very different and have some sniping back and forth, yet I don’t see the same visceral suspicion across the sides of town compared to say how Louisville’s South End (mostly working class white) sees the East End (the favored quarter). That helps explain why it took Louisville 40 years to build new Ohio River bridges, and why Cincinnati had to overcome unbelievable obstacles to build a streetcar.

These cities are also provincial and insular in their character. As a transplant to Louisville put it, “Louisville is parochial in all the best and worst ways.” These are cities with rich, unique architectural traditions, and with tremendously distinct local cultures compared to other cities in their region such as Indianapolis or Columbus, which have been largely Genericaized. So Cincinnati has its chili. St. Louis has its pizza. Pittsburgh even has its own yinzer dialect. In at least three of the four of these cities — I don’t know about Pittsburgh – the first question you get asked is “Where did you go to high school?” which tells you almost everything you need to know about them.

While provincialism is almost inherently negative as a term, this has big upsides for these cities too. They have an incredible sense of place and uniqueness. The brick houses of St. Louis are unlike anything else, for example. Again, the feel of these places is very notable in contrast to neighbors like Columbus and Indy, which give off a Sprawlville, USA vibe.

Trailer for film Brick: By Chance and Fortune. If the video doesn’t display for you, click here. Please ignore the unfortunate preview image.

I’ll give an example that illustrate this. Cincinnati arts consultant Margy Waller made a comment to me a few years ago that really stuck with me. She said that when people leave Cincinnati and come back, the stuff they did and learned while they were away might as well not have happened. She left and worked for several years in Washington, including in the Clinton White House. I’m not sure exactly what she did there, but if you’re working in the White House, by definition you’re operating at a bigtime level. But that’s barely mentioned in Cincinnati. Few people ever ask how her DC network or experience can inform or support the city.

Similarly Randy Simes is an instructive case. A graduate of the University of Cincinnati planning school, he got a job with a tier one engineering firm in Atlanta. But he also started and ran the blog Urban Cincy, which is a relentlessly positive advocate for the city and maybe its most effective marketing voice to the global urbanist world (the Guardian listed it as among the best urban web sites on the planet). Eager to come back to Cincinnati, he looked for a job there. But he couldn’t find one. Here’s a guy with 1) legitimate professional credentials 2) a top tier firm pedigree 3) the city’s most effective urban advocate 4) non-controversial, positive, and aligned with the political structure of the city and 5) he’s 24-25 years old and so it’s easy to hire him – you don’t need an executive director position or something. Yet no interest. Shortly thereafter he was head hunted by America’s biggest engineering firm to move to Chicago and then was sent on an expat assignment to Korea where he’ll be working on, among other things, one of the world’s most prominent urban developments (one that Cincinnati actually flew people in from Korea to present to them about). Jim Russell had a very similar experience with Pittsburgh.

The relationship of prophets and home towns has been known for some time, so I don’t want to pretend this is a totally unique case. But I can’t help but compare Randy’s case to blogger/advocate Richey Piiparinen in Cleveland, for whom an entire research center was created at Cleveland State (admittedly, he was already local at the time). I just don’t think Randy’s accomplishments outside Cincinnati resonated.

And secondly, these places do sometimes cross over into a sort of hauteur. I think because these were all very large, important cities in their earlier days and because they had so much amazing stuff, it bred a sort of aristocratic mindset perhaps. Having lived in both Louisville and Indianapolis, I clearly see the difference. In Indianapolis cool people will happily tell you how awesome they think St. Louis, Cincinnati or Louisville are. They’ll make visits to say the 21C Hotel or Forecastle Festival in Louisville and write and say great things about it and even how they wish Indy had some of those things.

But people from Louisville would rather bite their tongues out than say nice things about Indianapolis. If forced to, they will, but they do it in the most grudging way. I’ll never forget a travel guide for Louisville called the “Insiders Guide to Louisville” (I believe different than the one currently being sold under that name). In the intro they were bragging about Louisville’s totally legitimate food scene, but they had to throw in a gratuitous insult by saying something along the lines of, “Every city has good restaurants these days – even Indianapolis, we hear – but Louisville’s restaurants are truly special.” When Indianapolis Monthly did its “Chain City, USA” cover on Indy’s restaurants, I had to send it to my friends in Louisville since I knew they’d eat it up gleefully. (If you watched the St. Louis brick film trailer, you’ll also notice someone in it throwing a similar gratuitous dart at the Illinois brick used in Chicago).

Hot off the presses is this travel piece on Indianapolis written by someone in Louisville. As a travel piece, by is going to be positive by the very nature of the genre, but note the way the writer frames up the trip:

I bristle whenever I hear about flyover country — my home of Louisville is smack in the heart of what east and west coasters think is just the space they have to cross to get from one good part of the country to another — so I should be a little more open minded. But maybe because of my fondness for my hometown, it turns out I’ve been harboring a bit of the same snobbery that those fliers do — toward a northern neighbor.

My friend Kristian was bragging to me about Indy’s tech scene one day. I’d just gotten back from Cincinnati where I’d gotten to see their tech scene showcased, tour the Brandery accelerator, etc. So I said, “What about Cincinnati? Looks like they are rocking and rolling.” Kristian was like, “Oh yeah, they’re awesome. I was just down there and they totally get it, there’s some great stuff going on.” Then he made a comment that I think summed it up: “You know what though? They’re in love with their own story.”

That sums it up. These cities are in love with their own stories. That perhaps also explains a bit of it. With so many amazing assets it’s easy to be complacent. It reminds me of the famous quote from the triumphant (and boosterish) Chicago Democrat as Chicago started to pull away from St. Louis as the commercial capital of the Midwest: “St. Louis businessmen wore their pantaloons out sitting and waiting for trade to come to them while Chicago’s wore their shoes out running after it.”

If you’re too in love with your own story, you’re not going to work as hard as you should to take that story to the next level. After all, the story of these cities isn’t finished yet. But there’s a new generation in these places that aren’t wedded to the old ways. They love the story, but have some chapters of their own they want to write. As urban assets they have come back into fashion in the market, it will be interesting to see how they evolve. As the press for Pittsburgh shows, for example, there’s already plenty of signs of an inflection point. And in a region where places tend to flagellate themselves, having some cities with a bit of honest to goodness civic hauteur can actually be a refreshing change.

Good assessment overall. Of the cities mentioned I can only speak from St. Louis experience, but most long-time St. Louisans (and our politicians in particular) seem either willfully insular or completely oblivious to good, progressive things going on in other places. I don’t see things changing in the county municipalities any time soon, but at least there have been some signs of change in the city with the younger generation taking seats on the Board of Alderman. Political fragmentation is a HUGE detriment in St. Louis, both at the local and state levels. Recently the Mayor and County Executive have been assessing the regions feelings on reunification and city reentry into the county. As you might expect the effort has met with mostly resistance from the county munis, who’s officials don’t want to lose their jobs and clamor on about crime and bad schools and poor fiscal management when, in reality, the city is in better financial shape than many of those munis, some of which have begun losing their already meager populations. At the state level, the MO legislature fails to recognize St. Louis and Kansas City as the economic engines of the state and disproportionately allocates funding for rural infrastructure. As an example, MO ranks 36th in transit funding and 2nd in highway miles per capita. So basically progress in St. Louis is a constant, Sisyphean battle against local and outstate parochialism.

To your point about hauteur, I think a big part of that is resistance to the never-ending barrage of negativity that residents of places like St. Louis, Cincinnati, and Cleveland have to endure. And I don’t think it’s a bad thing. I doubt there are many in these cities that don’t recognize the need for improvement, but when you’re constantly told that the place you love sucks it wears you down. Focusing on the positives it what keeps many people going.

Pittsburgh has the where did you go to high school thing going on. It also has Solipsism. Well said.

But the pride thing is very different. In spite of the great built assets- Pittsburgh was a working class place- most known around the world for being ugly. Carnegie moved to NY & then Scotland. Frick & Mellon put their main art collections in NY & DC. Houses were built on hills to avoid the smoke rather than gaze at the views.

There is still a- I can’t believe they like us; I can’t believe they are investing/ building here- thing going on.

The upside to this is that the city doesn’t feel like a museum. Development patterns are pretty relaxed outside of a few places like The Mexican War Streets.

Cleveland seems similar to Pittsburgh that way- except more so. (I’m from New Jersey, I don’t expect too much if the word ended today I would adjust)

Pittsburgh is slow-growing because it had to build an entirely new economy from scratch during the last three decades of the 20th Century, and only in the last 10 years has the effort even begun to bear fruit. I’m not so sure about the other three cities. They all had industry, but not to the degree that Pittsburgh had. Maybe they just get overlooked because most people don’t look any farther than the East Coast, Great Lakes, West Coast or Texas for big cities.

These 4 cities may be in love with their own stories but they show a very insecure face to the rest of the world. They are like the kid and some adults who constantly needs approval. And while I am surprised at their anemic growth given their assets…..esp with Pittsburgh and Cincinnati……, I frequently wonder if the majority of their populations are happen with that level of growth. It could be they are getting something as a tradeoff for the lack of growth…stability/consistency? Maybe that’s worth the lack of advancement seen in other cities.

@John: I can’t get over how much Pittsburg and Birmingham are alike. But then it used to be called the Pittsburg of the South. On a smaller scale; B’ham metro about 1.1 million now.

I think what sets Pittsburg (and B’ham) apart from Louisville, St. Louis and Cincinnati. Sometimes you need to be kicked in the head. For B’ham, its just been one thing after the other: Civil rights, steel collapse, textile collapse, rise of the national chain stores, …..

But you know what, it has made the city a better place. A much more diversified economy now. Banking (Regions, Compass), insurance (Protective Life, Liberty National), meds (UAB, Andrew’s clinic), numerous small engineering firms you’ve never heard of, comms (ATT has a huge presence in the city), materials (Vulcan Materials), energy (coal, gas, oil), cars and car parts (Honda, Mercedes, Hyundai, Kia), and so forth. And you know what; we still make a lot of steel.

On a social level, it’s a lot better place too. Is everything great and wonderful? No. More or less we’ve reached an equilibrium that most people are OK with: I don’t think you’ll ever see s Cincinnati style riot erupt here.

Maybe Birmingham is the, er, Birmingham of the south….

While we’re on the subject of the South…

I definitely picked up on a lot of these same qualities in New Orleans, down to a T. Post-Katrina, though, it seems like many of these introspective qualities are slowly melting away. There is an undeniable and growing number of transplants in the city – it’s the usual story, with quality of life and cheap prices luring the creative class, but the ebullient culture of NOLA seems to be especially effective at luring outsiders.

Just in the last 18 months, I noticed that the city’s once-marginalized Vietnamese community has started to open a sizable number of businesses and restaurants in the city center. New Orleans’ old-style Yats and African-Americans had no use for Vietnamese food, but the transplants love it.

@Aaron: You’re right. I keep drawing a blank when I try to think of a southern place that’s even a little bit like b’ham. Chattanooga used to be fairly indusrilal but not so much any more i think. Augusts huge industrial chemical plants. Houston about the best I can come up with.

“Pittsburgh is slow-growing because it had to build an entirely new economy from scratch during the last three decades of the 20th Century.”

IMHO, this is only partially true. Many of the main components of the new Pittsburgh- PNC, Mellon Financial, Westinghouse, Alcoa, Several national law firms, The major universities already were big institutions. Ditto, with much of the great housing stock & public buildings.

The end of major industry, sort of revealed these things. Wasn’t till about 1985 that a few public critics (Franklin Toker, Brendan Gill) noticed how pretty the city was.

The city had other assets like the cultural mecca of the Hill District- and an extensive street car system which were fully appreciated only after they were gone.

The city went through several decades tearing at itself trying to imitate other places.

To large extent, the city is just starting to recover from things done during that period.

“With so many amazing assets it’s easy to be complacent.”

I really don’t think this describes what happened to Pittsburgh.

Pittsburgh’s early leaders were very ambitious in building long term assets- and were very aware/ obsessed with the way the city was perceived.

Later the establishment rushed to tear down old districts like the Hill, East Liberty and the heart of The Northside to be on the cutting edge of suburban expansion.

The damage done by this ill placed “renewal”- probably set the city back several decades and was at least as damaging as industrial decline.

@John:”The damage done by this ill placed “renewal”- probably set the city back several decades…” Exactly. I think cities should take a very hands-off approach. Step in under the most direst of circumstances. No matter how well intentioned the intervention might be, your’re just as likely to be wrong as right. Focus on many samll things. If they work out, then double down.

@John Morris,

“Renewal” in Pittsburgh sounds a lot like what happened to Cincinnati’s near west side in the same spirit. By all accounts, I-75 paved over what was essentially a substantial extension of Over-The-Rhine, a loss to the city of such immense value that it seems downright criminal today.

I certainly grasp the history and forces behind such initiatives, but I remain amazed by how our cities have been so maligned, undermined, and generally under-appreciated in American society. It’s as if we have a collective built-in preference for mediocre, substandard development. We simply cannot grasp and appreciate the urban treasures that have been built and bequeathed to us.

Besides rivers, another geographic connection is that all four cities are “hill cities” — basically places where rolling topography meets the river. Not unusual — Kansas City, a relatively prosperous Midwest river town shares the same topography, and Omaha has many of the same characteristics. Not that these places have managed their images all that well vis a vis their topography. Too many have hung onto their long dead river town image. Today, the rolling topography that helps define them physically is poorly understood. to outside audiences. All are seen as boring flatlanders. The reality is much different.

Early on, the rivers provided connections that made these cities early “global” cities based on their economic opportunities and immigration patterns. Now, not so much. They were all superseded by Chicago and its rail and Great Lakes waterway connections.

From a purely image standpoint, what disappeared is the sense of romance each city had 100 years ago. Yes, they were all gritty industrial centers, but they had exciting urban characteristics that were more similar to contemporary European cities than 21st century American cities (St. Louie, I’m looking at you).

It all went away. Some survives. A lesson to us all.

I totally agree.

In this respect, Pittsburgh is different from Birmingham. A) It was not just a steel town, but a headquarters, business service & banking center for leading industrial companies- PPG, Koppers, US Steel, Alcoa, Westinghouse, Gulf.

By 1960, most of the major mills had already shifted out of town & the city was more a control center for a vast complex of regional mills & industrial towns.

Had leaders sat back and let the chips fall- assets would have revealed themselves. At best, they were fighting the last war.

A big problem I have with Aaron’s focus on leadership and ambition is it assumes a group of people in a room can fully grasp a city’s assets. This is the fatal conceit of central planners.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Fatal_Conceit

@Ziggy “basically places where rolling topography meets the river.” It’s intersting that cities in question are not on little placid rivers (like San Antonio, Indianapolis, Chicago, or Miami) but potentially raging killers. The river is dyked up, levied, to otherwise corraled. No one in their right minds builds anything in the flood plane. Further, the rivers play virtually no part in the modern economy. It’s almost something you turn your back to. I’m sure at one time there was a “river street” in each city that was the epicenter of economic activity in the area.

Is there an example of a city on a “big” river that has truly turned it into an asset?

John Morris, I think Aaron’s focus on leadership (their strengths and / or shortcomings) is spot on. That said, your comment regarding their ability to “fully grasp a city’s assets” is also spot on.

The leadership of major metropolis’ has to somehow split the difference between their immediate and long term economic interests. In a heavily finkncialised economy, all too often this means their interests lie far beyond their local civic borders. Aaron — with his theory regarding the presence of local billionaires — is far advanced in his thinking regarding their current value to their local communities.

I doubt Pittsburgh’s leaders of the 1960s welcomed the national and global policy changes that essentially destroyed their industries. But they had a stake in the global economy even then, and they adjusted. And got wealthier.

Could they have made difference if they were more proactive as leaders of the national and Pittsburgh’s interests?

Maybe. One way or the other, Pittsburgh workers — like every other Midwestern industrial center — got hosed. The local community leaders came out okay.

Thus the scrutiny of local leadership deserves all the attention Aaron cares to give it.

wkg — Excellent observation.

You make a great point — in the highly channelized riverways of the Ohio, Mississippi and Missouri Rivers, the waterfronts of Midwestern cities have been not fully leveraged as economic assets beyond industrial.

A lot of places like Dubuque, Davenport and Burlington, Iowa (and I know I’m missing others) have been working on it. But it’s a tough row to hoe.

I think Aaron’s point about river cities only fully applies to Cincinnati, Louisville, & New Orleans which became major cities primarily based on river trade & were sort of bypassed by later transport methods

Pittsburgh started as a river town, but entered peak growth based on railroads- and is really a railroad city (Making it closer to places like Johnstown, Altoona & Reading)But it’s really a hybrid- needing both water transport for coal- & rail to ship ore & finished steel.

St Louis is sort of a hybrid/ rail river town that was a huge hub for western expansion.

Nashville has a river but is more a railroad town- same with Chattanooga. Kansas City has a river but I think became a big city based on railroads.

I think we can sort of throw Buffalo into this mix- as a place developed around bulk water cargo trade, that has sort been bypassed.

Wrench in the works: Minneapolis-St. Paul is a river and hill city that once depended on agricultural trading, milling (water power) and water shipping just as the other four. They even had Germans (but they were German Lutherans).

Today its metro is bigger than any of the four other “big Midwestern River Cities” Aaron mentioned. MSP has higher GDP per capita, is growing faster, and has higher income per capita. It is not especially diverse, but it does not have a troubled racial past or present.

Compare. Contrast. Explain.

“These 4 cities may be in love with their own stories but they show a very insecure face to the rest of the world. They are like the kid and some adults who constantly needs approval.”

Here’s another example of the ignorant condescension that people from these cities have to put up with. It’s a double standard: people in “hot” cities are allowed to gush endlessly without reprimand, but if anybody from the rust belt shows a little pride we’re accused of overcompensating for our insecurities. We’re constantly berated as failures in the media (which happily reinforces negative perceptions in the interest of web traffic) and then if we dare talk about our assets we’re trivialized as children looking for approval.

I think if one looks at Minneapolis-St Paul’s growth period- rail probably already existed and was a big factor.

A big reason for the cultural difference between rail & highway cities and old river towns is natural monopoly.

It takes time & capital to build a railroad, but often there are many possible routes. Cities have to fight to build & keep connections. Old river cities- often develop at points with critical characteristics that can’t be duplicated.

Natural monopoly can breed a culture of complacency.

^^ yeah, Minneapolis is young enough to have avoided much of the entrenched, concentrated poverty associated with the ghettoization of black people after the first wave of the great migration.

“Is there an example of a city on a “big” river that has truly turned it into an asset?”

This is a topic that caught my attention recently. I would say Portland (with the Wilmamette and Columbia Rivers) is a work in progress, but I’m not aware of a good example. The Ohio, Missouri, and Mississippi Rivers present some pretty big challenges in terms of potential for disasterous flooding. I know that in St. Louis last year, the Mississippi River varied in elevation by more than 45 feet. It’s a challenge to develop an intimate urban riverfront with this type of river. I think that this led to an even greater long-term challenge – which is the placement during the 1950s-1970s of major freeways along the riverfront of nearly all of these cities. At the time, this probably seemed like a great planning option – based on the blighted industrial land that was present along these rivers – in part due to their pattern of industrial developmnet and in part due to the unsuitability of these areas for residential or commercial development due to the threat of flooding. Now – these freeways cut off the downtown of these cities from what could be one of the most attractive natural amenities.

Milwaukee has seen a remarkable transformation of its urban riverfront (particularly the Milwaukee River) – with probably 90% of the former industrial areas converted to residential or recreational amenities. Probably 90% of the railroad infrastructure has also been removed from former waterfront areas. The Milwaukee River, however, is a much smaller river – and in the downtown area is actually part of on estuary with Lake Michigan – resulting in an urban riverfront with water levels that vary by a few feet per year.

“This suggests a broader challenge: if urbanity and quality of life are so determinant of economic success, why aren’t these places juggernauts? It’s not that they are failures by any means, but they are long term under-performers.”

I think there is a time factor involved. How long should it take a city to recover from industrial and demographic collapse? Arguably it took Boston 30 to 40 years in spite of having some of the most extraordinary assets of any city in the U.S. (or the world — in terms of top notch universities). The urbanity and quality of life in these four river cities is still a work in progress, in spite of the beautiful old buildings and cultural assets. There’s still a lot of blighted land to be cleaned up and repurposed. This is hard work. Another factor was noted by some of the other commentators — which is that the initial physical decline was exacerbated by some of the urban renewal projects of the 1960s though 2000s.

Cincinnati has done some nice things with its riverfront, but the downtown is ringed with massive freeways – and not much different from Dallas in this characteristic.

Interesting insights and examples related to the attitude and perhaps parochialism. I don’t recall having ever been asked once as an adult in Milwaukee where I went to high school.

@John “I think if one looks at Minneapolis-St Paul’s growth period- rail probably already existed and was a big factor.” No doubt it did. But a bigger factor is that is sits right on top of an agricultural gold mine.

I see a great future in store for parts of the country that are into agriculture in a big way. That would certainly include St. Louis and Indy. Maybe Cincy too.

@Adam “These 4 cities may be in love with their own stories but they show a very insecure face to the rest of the world. They are like the kid and some adults who constantly needs approval.”

I think the Midwestern cities cited feel they are very much in Chicago’s shadow. Well B’ham is very much in Atlanta’s shadow. It’s almost a very global city (and you don’t know how it makes me want to throw up to type that), and well we’re just, well B’ham. Do I resent this situation? Not a chance. I’m glad Atlanta is as successful as it is. I’ve lived in both extensively. I like B’ham more, a lot more. Atlanta is close enough that I can run over to catch a show, or shop, etc. Even just to go to a party (I still have a lot of friends in Atlanta). Atlanta is Atlanta and runs in different circles. Good for them.

It’s kind of the best of both worlds. It is hard to maintain the proper perspective on things. A certain degree of modesty is needed if you live in a “secondary” city. A certain amount of realism too. B’ham is the minor leagues. I just have to get over that. In the grand scheme of things we’re just a back-water. But it’s a very nice backwater.

@Roland S, I left out Memphis and New Orleans because I don’t know them well, but NO would appear to fit the bill. It got very big very early compared to other cities, unique culture/history/architecture, slow growth, insular, etc.

@Ziggy, I tried to mention the hills and such, but should have stressed the river valley geography. To get to my house in Southern Indiana you had to drive up a major hill into the “knobs”. Cincinati has some similar features, like the long, steep hill from downtown to uptown.

I do think people forget that these rivers have massive flood plains. Look at the photos of the 1937 flood in Louisville, for example. Without the huge floodwalls, there’d probably be serious flood disasters ever couple decades. Also, the rivers were industrial. (That was even true in Chicago and Milwaukee, one reason those cities were able to keep their lakefront’s relatively pure). Buffering the industry on the river from downtown and neighborhoods with an elevated freeway in the flood plain (as Louisville did with I-64) wasn’t necessarily a horrible decision at the time. It looks bad in retrospect now that the industry is gone. I’m not sure we remember the extent to which managing pollution and the negative effects of industry was a huge focus in cities years ago.

@Chris Barnett, the Mississippi is not that wide at Minneapolis. Thus it doesn’t produce the same sort of barrier effect. That’s one reason that unlike the other cities, it doesn’t have an unbalanced development pattern. (In fairness, Pittsburgh’s rivers aren’t that wide either). More to the point, Minneapolis didn’t boom until after 1880 – much later than the other cities. It only had 47,000 people in 1880. Louisville reached the same population just after 1850. Cincinnati by 1840. I don’t think Minneapolis is a river city in a meaningful sense even though it is on the river.

I don’t know the cities discussed here all that well; I probably know Cincinnati best. But I won’t dispute anything said here based on observations made to me by natives of the cities. There is something very different about them.

Maybe there’s a source for the insularity and solipsism. All four cities were initially settled as outposts, far away from anyone or anything, and had to develop as if nothing else were around them. Also, they are distinct from other Midwest cities in that they were settled by settlers from Appalachia, who perhaps brought notions of insularity with them. For comparison, Indy and Columbus could’ve developed similarly to these four, but as state capitals they never had the outpost mentality the others had. And the Twin Cities’ settlement pattern (from New England and Northern Europe) made it a very different river city from the beginning.

“I don’t think Minneapolis is a river city in a meaningful sense even though it is on the river.”

From what I read, Minneapolis did start as a river city- more the way, Lowell & Providence are. The city is located at a falls that powered flour & lumber mills.

It had that “natural monopoly”, advantage that often breeds complacency- but managed to push beyond that.

pete-rock, a gentle correction regarding Columbus and Indy and Appalachia in general.

Both have long had large Appalachian-American populations, (in Columbus, including my family on both sides). Both were “new cities” created in the early 19th Century in the middle of what was then wilderness…they were by definition “outposts”. They were founded just a few decades after Cincinnati, pre-rail.

Current exurban CMSA counties in the Columbus and Cincinnati metros are part of the legally defined Appalachian region (see http://www.arc.gov/counties). Pittsburgh’s entire metro is entirely Appalachian. None of the Louisville metro is in the Appalachian portion of Kentucky.

I find it ironic that these cities still struggle with their riverfronts when you look at a city like Indianapolis, which rebuilt a canal. Creating major development along it, leading to White River State Park with its many musuems, entertainment spaces and zoo with a pedestrian bridge linking the canal area to the zoo. This was done long before any of the “river cities” in this piece got serious about doing anything.

There is a lack of collaborative spirit in Cincinnati for example. You cannot get city government, the business community and neighborhoods on the same page about ANYTHING. It starts with leadership and neighborhoods actually trying to turn themselves around, often find themselves in adversarial positions with city government who can not seem to get out of a blight=bulldozer mindset.

Personally I’d love to do “big picture” but I can’t, because the city can’t see big picture, much less implement, because it requires leadership and consensus building.

As a community leader I have to fight the city tooth and nail to do what we do, to try and revive my Knox Hill Neighborhood. I’ve lived in Louisville, I’ve lived in Indy and I live in Cincinnati where despite some recent successes, are mired in a 1960’s development mentality of bulldoze it and they will come.

Aaron and John: From Wikipedia, Minneapolis grew up around Saint Anthony Falls, the highest waterfall on the Mississippi. In early years, forests in northern Minnesota were the source of a lumber industry that operated seventeen sawmills on power from the waterfall. By 1871, the west river bank had twenty-three businesses including flour mills, woolen mills, iron works, a railroad machine shop, and mills for cotton, paper, sashes, and planing wood.

Yes, the timing is later than the lower River cities, but the city grew due to its natural economic monopoly over the region, similar to Cincinnati, Pittsburgh, and St. Louis, and became dominant regionally in the rail era.

Cincinnati was established by a lot of people from the New Jersey area as land was given to veterans of the Revolution in lieu of cash.

The east west divide in Cincinnati goes backt the era when transportation was an issue. You had to cross a river, train tracks & then climb a muddy hill to get over to the west side. When those towns were annexed, there were no relations between the established center & east portions, so the western neighborhoods had stalled improvements & developments. The current attitude that nothing has changed is ridiculous. There seems to be a lot more cooperation between multiple jurisdictions in NKY than there is between neighborhoods within Cincinnati.

Simes was actually persecuted in Cincinnati by people who routinely denigrate the city but are now promoting the city for a national political convention. I’d guess there’s a degree of schizophrenia involved in the city, too.

@Chris Barnett

One of the biggest figures in Minnesota history is not Lutheran, but the hard driving Scotch-Irish, James Jerome Hill who built the Great Northern.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_J._Hill

I sort have a different spin on Cincy & Louisville. Considering they lost a huge logistical advantage to railroads so early, they managed to do pretty well.

I don’t fully buy the “great man” theory of history, but JJ Hill, like Carnegie fits it.

“The Great Northern energetically promoted settlement along its lines in North Dakota and Montana, especially by German and Scandinavians from Europe. The Great Northern bought its lands from the federal government–it received no land grants–and resold them to farmers one by one. It operated agencies in Germany and Scandinavia that promoted its lands, and brought families over at low cost. The rapidly increasing settlement in North Dakota’s Red River Valley along the Minnesota border between 1871 and 1890 was a major example of large-scale “bonanza” farming.”

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_J._Hill

Hill was also a critical figure in fully developing the Mesabi iron ore deposits, along with Oliver & Carnegie.

Chris, you’re mistaking the Ohio River cities for New England mill towns. These were transportation centers. Louisville is where it is because people had to portage around the Falls of the Ohio at a time when the rivers were the interstate highways. I think using the mill examples almost makes my point. I’m sure being at near the northernmost navigable point on the Mississippi had something to do with it, but the development trajectory was different. Just look at the architecture of Minneapolis. It’s much like an Indy in a lot of ways.

I think similarly KC was on the Missouri River but not a river city in the same was as Cincinnati.

@Chris Barnett: You’re actually agreeing with the point I’m trying to make. I’m suggesting that Indy, Columbus, Cincinnati, Pittsburgh, St. Louis and Louisville all have initial settlement roots that come from Appalachia. People came from other parts of central Pennsylvania, West Virginia, Tennessee and Kentucky to establish these cities, and they’ve made a long-standing cultural mark. What distinguishes Indy and Columbus from the rest is that as state capitals they quickly became the focal points for entire states that meant they didn’t develop in the same vacuum the others did. They were self-sufficient cities that suffered (to varying degrees) when rail became the dominant mode of travel.

I’ll make this point again. I see a considerable cultural difference between Great Lakes and River Valley Midwest that is often obscured because state boundaries overlap:

http://cornersideyard.blogspot.com/2014/02/repost-five-midwests-part-ii.html

It makes sense when you consider specific cities: Toledo is more like Detroit than Columbus, despite the fact both are in Ohio, for example; South Bend is more like Chicago than Indianapolis. Why? Toledo and Detroit, or South Bend and Chicago, share a similar settlement history, totally distinct from Indy or Columbus. I maintain that settlement histories can tell you a lot about how cities approach their futures.

@Pete Rock

This does not sound accurate. I think the Ohio itself was the main way most early residents arrived in Cincinnati & Louisville.

Cincinnati also adopted somewhat well to the railroad age. Proctor & Gamble was a very early national marketer of consumer goods.

What Pittsburgh failed to adjust to is the auto age. Everything about the city/ region is right for rail or streetcars- and not right for much else. The busway concept sort of works as a replacement for rail in some areas.

@ John Morris:

Yes, the Ohio did bring people to Cincinnati and Louisville, and even St. Louis. But the people who got there were the ones who had the easiest access to it — Appalachians. There were not a lot of Bostonians making it to Cincinnati, for example, until after the railroads. Expansion-minded New Englanders prior to the 1840s usually followed the Erie Canal/Great Lakes route to Buffalo, Cleveland, Detroit, Chicago and Milwaukee.

I generalize here, but if you look up the history of almost any town north of I-70, you’ll see more often than not that it was founded or settled by people from New England or New York. South of I-70 you’ll find cities founded or settled by Revolutionary War vets from KY, PA, TN or what is now WV

John, Pete Rock is correct. People came overland to Pittsburgh or Wheeling or Parkersburg from the Appalachian highlands (or downriver from “inland” West Virginia and Kentucky), thence downriver to Pomeroy, Gallipolis, Ironton, Portsmouth, Cincinnati (Ohio); Aurora, Madison, Clarksville, New Albany, and Evansville (Indiana). The southern parts of both states were settled “up from the river” in the early to mid 1800s.

Pete, we agree on this: Cleveland, Toledo, South Bend, and Gary were largely settled by later immigrants arriving at Ellis Island and taking the NY Central to the industrial Midwest. Because Columbus and Indianapolis were on another main east-west rail line (to St. Louis), they did get some immigration in the industrial age also. But they were already settled cities by then.

It is not for nothing that US40 in both Ohio and Indiana has long been considered the divide between northern and southern. It is both a geographic and a cultural divide, or at least it used to be.

Thanks everyone. This has been a very informative thread. It’s pretty easy to see why St. Louis and Pittsburg are exactly where they are. Then @Aaron “Louisville is where it is because people had to portage around the Falls of the Ohio at a time when the rivers were the interstate highways.” Is there any particular reason Cincy is exactly where it is and not say 10 miles up or down river?

I take it that Columbus and Indy were established arbitrarily as capitals — and basically didn’t exist prior to the designation. I know Tallahassee was selected as Florida’s capital because it was more or less exactly half way between the principle cities in the state at the time, Jacksonville and Pensacola.

Wow, I don’t know but this just doesn’t sound right.

It was a lot easier to travel by the Ohio River than over the mountains into what is now West Virginia. Tennessee was mostly settled after The Revolutionary War. Daniel Boone first got to Kentucky in the 1767.

Typical traveler went to Pittsburgh overland & then down the Ohio. Pennsylvania, New Jersey & Virginia immigration sounds right

By 1850, 43% of St Louis’s population was foreign born.

https://stlouis-mo.gov/government/departments/planning/cultural-resources/preservation-plan/Part-I-Peopling-St-Louis.cfm

“By 1850, 43 percent of all St. Louisans were born in either Ireland or Germany. Irish immigrants often brought limited skill levels, putting them into direct competition with free blacks in cities for lower level jobs. In this case, economics drove politics; Irish immigrants in cities tended to be strongly pro-slavery, out of fear that liberating African-American slaves would create a glut of unskilled labor, driving wages even lower.”

@wkg in bham, I have heard that John Cleves Symmes expected the major growth would be to the west of where Cincinnati grew. I imagine, Cincinnati, being between the Deer & Mill Creeks was a factor.

@wkg in bham

I agree with you. (And I just want to clarify that the quotation is not mine—it’s from Alki’s comment above.) Midwestern cities definitely feel that they’re shadowed by Chicago, but the resentment/defensiveness (to the extent that it exists) is not a result of Chicago being a great place, it’s the result of places like STL, Cleveland, Cincy, etc constantly being held up by the media as foils to places like Chicago, NYC, LA, SF, etc. and the resulting barrage of negativity (i.e. bashing as opposed to constructive conversation) that it generates. I don’t resent Chicago at all for being a great city. What I resent is the sense of superiority often projected by people in tier 1 cities. Certainly some people are unrealistic about their boostering. I would never assert, for example, that STL is as economically healthy as Chicago, nor as ethnically diverse, nor that our downtown compares architecturally. However, I definitely don’t think that people in “secondary” cities have to be modest to the point of self-deprecation which, it seems, is often expected. Besides the modesty thing works both ways: nobody likes a braggart.

@Pete Rock

This link seems to confirm the most logical story that most people took the easy way into the region down the Ohio- or across the flatter Ohio plain.

http://www.ohiohistoryhost.org/ohiomemory/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/immigration.pdf

The largest number of migrants in the pre-1850 period came from the Middle Atlantic states, particularly Pennsylvania. Migrants from this border state were mainly Germans and Scotch-Irish and constituted 43% of all migrants

during the first half of the 19th century. Most of the migration followed routes along Ohio’s mid-state drainage divide and the southwesterly slope of Zane’s Trace. The middle regions of Ohio are thus often connected with a

strong German influence, manifested in distinctive log cabin styles and barn construction, and pietist religious beliefs. Pietism was a protestent revival movement, emphasizing an earnest and heart-felt approach to religious devotion. New Jersey and its neighboring states were also well represented

in the settlement of Ohio, largely due to the Symmes Purchase, a real estate venture organized by a prominent New Jersey judge, John Cleves Symmes.

The majority of southern migrants came to Ohio from Virginia and settled in the Virginia Military District lands located in the west central portion of the state. Southern influence in this region can be seen in the greater number of

large farms, the predominance of the I-house style of dwelling (long brick houses with a double porch), the larger percentage of Scotch-Irish, and the prevalence of Presbyterian religious beliefs.

As an aside, I remember an article I read a number of years ago. You have to be real careful driving around St. Louis. Some of those small towns west of St. Louis are very poor and basically exist by writing speeding tickets.

Over in East St. Louis there are these huge indian mounds. St. Louis was the largest indian city north of mexico city.

Cincinnati was largely an industrial center and the majority of the city between 1870-1910 was settled by immigrants of German, Russian and Italian descent. OTR was essentially a “German Ghetto” using the ghetto in the fact they largely had their own largely German speaking community there.

The next wave of immigration was Appalachians who came to Cincinnati looking for work in the industrial plants that were in the Mill Creek valley in the 1930’s, OTR became a Appalachian ghetto in the real sense because it was a poor neighborhood, The next wave of people to Cincinnati were southern Blacks who moved to Cincinnati post WW2, again looking for factory work. OTR became a Black ghetto. The latest wave of immigration are younger professionals (mostly from other states) Now OTR is becoming a mostly white Affluent Ghetto ( with property selling at 300.00 a sq ft).

Cincinnati’s economy was always manufacturing based and that has been moving out of the city to nearby counties, leaving the uneducated poor behind. Cincinnati like many cities has become very “welfare dependent” and city leaders have become dependent on maintaining that influx of money, building more low income housing and maintaining welfare programs.

There are competing factors now. The city is starting to realize the rebirth of its downtown and poor are getting pushed to the townships. Cincinnati has always been obsessed about its population which has declined to 295,000 in 2010. But bear in mind Cincinnati always had high density poor population of laborers and factory workers so it had population but not a wealthy one.

The real issue for Cincinnati is how it grows effectively and the competing forces of those who want to maintain that welfare based status quo vs those who are trying to turn the city around. Therein lies the issue, how to get things done with two forces with different views who only see their side.

Cincinnati based on my experience, resents outsiders, and insiders, who do not respect their belief that Cincinnati is this “perfect city”. They especially do not want to be told, or worse yet, shown, that outsiders can achieve results they can’t. There is an inability to adapt to changing circumstances and the city lags because of it, nor can they grasp the reality, that Cincinnati is more of a large town (in terms of the way its run) than a major city like Chicago.

@ John Morris:

I feel like we’re saying the same thing. Maybe you’re recognizing a distinction that I’m not — the Scots-Irish of KY and WV versus the German/”Pennsylvania Dutch” influence that came from PA. To me, they both came down the river to settle the river cities and established different cultural characters there than the New Englanders further north.

Thanks. I guessed the Appalachian migrants mostly came later chasing industrial jobs.

“Cincinnati’s economy was always manufacturing based and that has been moving out of the city to nearby counties.”

This is the other thing I guessed. If Cincy is partly a city of hills & valleys, it probably lacks the space in town for large footprint modern manufacturing plants.

Like many cities it has failed to transform former industrial areas like Camp Washington to a mix of other uses- like offices, retail residential & light manufacturing.

Where are the main regional manufacturing districts today?

Could the city eventually evolve towards a San Francisco model where reverse commuting is common?

@john, Most of the manufacturing is North and East of the city along I 75 towards Dayton.

The San Francisco analogy is perfect . Cincinnati could support a reverse commute. Many buildings downtown that once were offices are now condos. There are neighborhoods like mine, Price Hill, Fairmount etc. that overlook the downtown core that have the potential to be very high end housing.

The problem was the city pushed low income out there when OTR was emptied out post riots. City leaders do not understand that everyone will not want to live in a 270K 900 sq ft condo and single fam homes will be highly desired.

Architecturally Cincinnati has the finest collection of Victorian Architecture in the Midwest. Cincinnati is a bit of an urban planners nightmare too, for example I have 600 sq ft shotguns on my block and 4000 sq ft Second Empire A story house. But that diversity allows for greater pricing diversity that should eliminate the total gentrification in SF that is pricing out the middle class.

The city solution once they throw low income in a neighborhood has been to bulldoze it when they leave. “Blight abatement” keeps city inspectors busy, the demo contractors happy and destroys the property tax base. The city will demo over 250 properties in 2014 at a cost of millions of dollars yet only allocated , 200K on stabilization city wide being spent on two small projects. Yes they are shooting themselves in the foot and that gets back to lack of leadership ( and well trained individuals) in city government. You have people with high school diplomas running departments.

The city still follows the 1960 urban renewal model. Which is one reason it lags behind other cities.

It could be so much more.

That is what I thought- probably, the land north starts getting flat.

I love the housing diversity. Pittsburgh has a lot of areas like Shadyside with all kinds of property types.

Pittsburgh is starting to have that relationship with northern suburbs like Wexford, Cranberry & Warrendale

If you want/ need a big footprint property for manufacturing or research-you are likely to end up there. The housing stock, however, is vastly inferior to what Pittsburgh offers.

Reverse commuting is a likely trend here. My girlfriend does it.

In an ideal world, the city and northern suburbs would be connected/ oriented around a light rail system.

This is quite a fascinating topic. This discussion obviously points to the fact that there are numerous things at play here. I think the proximity of these cities to one another is another factor to consider. Aside from the East Coast, I-95, I can think of few other areas in the country that have so many, what I would call major cities competing for talent, resources, and jobs as the I-71/I-70/I-65 Bermuda Triangle (Indianapolis, Cincinnati, Columbus, Dayton, and Louisville with Lexington as a satellite). Perhaps Charlotte, Raleigh, Greensboro.

Can the market sustain so many cities in such a small area given industrial decline and the rise of the sunbelt? Especially when the balance of competition is tilted due to the fact that two of these cities are state capitals and one of those capitals is also home to one of the largest universities (and immigration magnets) in the country?

While cities have, no doubt, made some poor choices, the change of the geo-political landscape and immigration patterns cannot be ignored.

Well almost everyone I know in Indy (and I lived there for many years)works in the professional business sector. Indianapolis actually has very little major manufacturing left. They saw the writing on the wall 30 years ago and worked on getting corporate headquarters and service based businesses. Its big on tech and pharma and corporate centers and it has one of the largest convention businesses in the country and vibrant tourism base plus all the sports venues.

I don’t think Louisville is exactly manufacturing dependent either. Any city that hangs its hat on big manufacturing is doomed, its all about creating a diverse business/tech center with higher paying jobs that are key to success.

I think each city offers a slightly different niche and mix.

@Joe

In spite of their problems, the general stats show most of these cities, Louisville, Indianapolis, Columbus, Cincinnati are growing.

A) They are feeding on a general rural to urban migration.

B)They have shifted towards tech & services to a large degree.

C) The region borders on the growing mid South and benefits from that access.

D) They benefit from proximity & scale and may start to operate as one mega region.

My guess is the growth axis of the Ohio great lakes region is shifting towards the South and away from Toledo/ Cleveland.

Cincinnati’s founding is an interesting one as, from the outset, it was competing with neighboring settlements for supermacy. Originally settled under the name Losantiville (a poor attempt to fuse French, Latin, and English to refer to the village across from the Licking River), what is now Cincinnati competed with a settlement to the west on the Ohio known as North Bend, and a settlement to the east on the Ohio River at the mouth of the Little Miami River, known as Columbia. Though Columbia flourished first due to its fertile soil, its low lands were very prone to flooding and it was abandoned. North Bend failed to grow due the fact it lacked enough relatively flat, build-able land to allow for expansion. Losantiville sat across from a river that fed into Kentucky which was more developed at the time. It’s topography was also friendlier. The basin was large and a significant amount of it was on a plateau allowing for easy expansion into areas that were not susceptible to regular flooding. The locating of Fort Washington at the settlement pretty much sealed the deal.

“I can think of few other areas in the country that have so many, what I would call major cities competing for talent, resources, and jobs as the I-71/I-70/I-65 Bermuda Triangle (Indianapolis, Cincinnati, Columbus, Dayton, and Louisville with Lexington as a satellite). Perhaps Charlotte, Raleigh, Greensboro.”

Check out Houston, Austin, San Antonio, Dallas/Forth Worth, Oklahoma City.

Notice how the growth rate of one seems to boost the entire region. All of these cities are growth magnets.

Raleigh/ Durham is now feeding off Charlotte.

@ John

Austin, San Antonio, Dallas/Fort Worth are relatively close to one another but not nearly as close as the Cincy/Indy/Louisville/Columbus triangle. I believe the cultural differences between those Texas cities are greater than what you would find separating someone from SW Ohio, Central Indiana, or Northern Kentucky. That aside, I think your point of each of those cities feeding off the growth of one another is valid and evident. It’s definitely a positive aspect that probably is not as well embraced as it should be, partially again due to the geographic restraints which don’t exist in the Texas triangle or North Carolina triangle but I’m pretty sure Aaron has posted pieces before speaking to the need for a better, more regional economic approach in the Midwest, even if it means ignoring state borders.

I’m not a huge Richard Florida fan but his point about mega regions seems very valid.

Proximity = opportunity, if you grasp it. Jersey City grabbed onto New York & Newark didn’t.

Honestly, I think the zero sum game concept is popular with city’s (like Providence, Baltimore & Hartford) looking for excuses.

The Tennessee River Valley and the lower Ohio River Valley (downriver from about Cincinnati) have what I call “Pennsylginia” culture, with settlers from Pennsylvania and Virginia moving their ways down the Ohio and Tennessee Rivers, and becoming the two main cultural influences. West Virginia, Kentucky and Tennessee weren’t as heavy on slavery as other Southern states, so that aristocratic brand of Southern culture never had the same level of influence.

Even the Shenandoah Valley has a bit of that “Pennsylginia” vibe due to the Philadelphia Wagon Road. That’s the one part of Virginia that doesn’t have either a hard-core Appalachian vibe or an aristocratic Tidewater vibe. If anything, it just feels like a southward extension of south-central Pennsylvania, down to about Harrisonburg or so.

Don’t forget Dayton is right in that box too, John, and both Ohio and Indiana have a bunch of smaller satellite cities an hour or less out from all the cities we’ve mentioned, including Newark, Springfield, Marysville and Middletown, Ohio; Muncie, Kokomo, Richmond, Anderson, Columbus, Bloomington, and Lafayette/West Lafayette, Indiana.

This is a pretty big urban region in less than a quarter of Ohio, about a third of Indiana, and a slice of Kentucky. The five big combined statistical areas together have a population of almost 9.5 million and that doesn’t count some of the Indiana satellite cities or Lexington. (I’d want to take time to do the math on land area before offering more characterization.)

In today’s world, I would wager that it is successful as a region because of logistics. UPS Louisville and FedEx Indianapolis are both giant airfreight hubs. One corner or another of the region boasts of being within 500 miles of some huge percentage of the US or North American population via highway and you can see miles of big warehouses near the interstates in all of the metros.

But Indy and Columbus seem to be capturing more of it. More GDP, more jobs, more population growth.

Exactly, there is a natural logistical advantage to this region over the area closer to the lakes. This grows as the Mid South region grows.

@Chris Barnett:

The Ohio and Indiana satellite cities you mentioned are, IMO, endangered species. You may have seen Aaron mention here that it’s looking more likely that a metro area has to have a minimum of 1M-1.5M residents to be at a viable economic scale, unless it has outsized assets or amenities (a state capital, a major university). I do think their best hope lies in connecting themselves with Indy, Columbus and Cincinnati, but they often view themselves as competitors to the big cities, not complements. That’s not a good place to be.

As to where these people are coming from. Rural to urban movement is number one, but I imagine northern Indiana, & northwest Ohio are the big relative losers in this game. Also, probably southern & central Illinois & southern Michigan.

If Cincinnati is tarnished as too socially conservative, these places are seen as hard core rust belt with massive brownfield issues, militant unionism and corruption.

Is DHL OPERATING A FREIGHT HANDLING CENTER AT CINCY INTERTNATIONAL AIRPORT? Logistics.

I think the slow growth rate for Cincy, Pittsburgh and St Louis may be explained in part by the fact that all three have many fortune 500 HQs, which by nature of mature industries are themselves slow growers in terms of employment; esp in the last 30 years of corporate down-sizing and off-shoring mfg facilities. We all seem to agree that innovation is the general answer to this. These larger Midwest cities are doing that, but as said above (David Holmes) it takes a long time to re-build. Remember “Rome wasn’t built in a day”. So our much loved Midwest majors will probably need 40 years to rebuild; as has also been stated above, with Boston supplied as an example.

The self concept these cities have; alternating love with defensiveness is understandable; esp with the Sunbelt getting all the glory and positive press. I believe we are at a tipping point right now. Advanced Mfg, advanced healthcare, logistics, professional services and much more are increasing the foundation beneath the Midwest larger cities in a way that will prove itself to be powerfully effective in reinvigorating the Midwest.

Regarding two issues which I see having the same solution: Major Metro competition and the darkening future for smaller metros less than 1 million population. If the Leaders of the Midwest, by the thousands, could see the strengths of super regional collaboration; along established specialized areas in all the complex economic relationships, the Midwest could be a powerhouse again in many fields. Such as healthcare, higher education, advanced mfg, logistics, busn services, energy extraction and more. Also, a more charitable attitude among ourselves will really assist the Midwest. “Midwest” is a world brand that simply needs new product development like any great company that became complacent.

One more thought: Let’s talk about Chicago’s slow growth rate. What are the causes of that? Is it an “insular, complacent, extreme conservative” social dynamic? I doubt it very much. Chicago has all the assets we talk much about in positive terms; culturally and economically. so why the very slow growth rate. Maybe each city/region has unique features that are hard to identify. Maybe it too has many mature fortune 500 HQs that are slow growers.

Maybe it is because the other Midwest metros are doing more for themselves business wise in terms of professional services of all types!

I would think an analysis of Chicago would be instructive to us all. I haven’t read Aarons many commentaries yet. Any quick summaries anyone can offer? Thanks.

When I was in high school and college in the 1970s, no one talked about the rust belt. My parents, conservative small town Republicans, complained daily about union strikes, how they were taking the country to hell in a hand basket, blah, blah, blah.

And then came the infamous Powell Memo and the controlled demolition of big labor, middle class wages and the big Midwest manufacturing cities’ quality of life.

http://reclaimdemocracy.org/powell_memo_lewis/

In the subsequent 40 years, the wealthy retreated to their urban enclaves as any smart third world oligarchs would do.

My apologies — I know this is only tangental to the discussions of Midwestern cities like Cincinnati (and it’s been a great thread).

But I also think those who grew up in the Midwest, and have witnessed first hand the systematic destruction or decline of its great cities like Cincy are only now becoming aware that outside forces had a tremendous hand in orchestrating this demise.

Globalism wasn’t the idea of GM, U.S. Steel or the big Midwestern banks — at least I don’t think it was. But globalism completely hosed — and continues to completely hose — not only the Midwest but also every other major city in the country.

One could say that Midwest manufacturing led the post WW II race to the top for middle class. And, thanks to the long and poorly understood affects of globalism, they have also led our country’s race to the bottom.

I can’t entirely blame our Midwest leaders and the main street middle class folks like my parents for having the rug pulled out from under them. They were inclined to believe our national leadership that their interests were being served. But great lies (like NAFTA) undergird the decline of our great Midwest cities. A great majority of folks bit on the lies and continue to do so. We’re only now beginning to understand the reality that got us here. And it’s all very, very disturbing.

@Dan Wolf – “One more thought: Let’s talk about Chicago’s slow growth rate. What are the causes of that? Is it an “insular, complacent, extreme conservative” social dynamic? I doubt it very much. Chicago has all the assets we talk much about in positive terms; culturally and economically. so why the very slow growth rate. Maybe each city/region has unique features that are hard to identify. Maybe it too has many mature fortune 500 HQs that are slow growers.

Maybe it is because the other Midwest metros are doing more for themselves business wise in terms of professional services of all types!

I would think an analysis of Chicago would be instructive to us all. I haven’t read Aarons many commentaries yet. Any quick summaries anyone can offer? Thanks.”

From my observation (others might have the hard data to back this up), Chicago has a very high churn in population. That is, it has a very high domestic outflow rate, while it has a good-to-high domestic and international migration inflow rate. That latter inflow rate plus births is slightly higher than the outflow rate. So, the growth rate is slow on paper, but there’s both the perception and reality of dynamism because there are constantly lots of people moving both in and out. The number of people in the Chicago area might not be increasing that fast (albeit it’s still so large that a slow growth rate will add a substantial number of people in sheer numbers), but *who* those people are keeps changing rapidly. In contrast, other Rust Belt metros with slow growth rates seem to have both low outflow and low inflow rates. As a result, that low churn can make a metro seem more stagnant and insular compared to a high churn metro with a similar overall growth rate.

@Dan Wolf – “I think the slow growth rate for Cincy, Pittsburgh and St Louis may be explained in part by the fact that all three have many fortune 500 HQs, which by nature of mature industries are themselves slow growers in terms of employment; esp in the last 30 years of corporate down-sizing and off-shoring mfg facilities.”

I think it’s a bit mixed here and depends upon what the Fortune 500 companies are actually doing. The high growth areas of Houston, Dallas and Atlanta are now only behind NYC as the home to the largest number of Fortune 500 companies (even more than Chicago). So, Fortune 500 companies in and of themselves aren’t drags on growth. Indeed, if you have Fortune 500 companies in a hot industry, that can fuel extraordinary growth. The main issue is that many Midwestern Fortune 500 companies are in, as you’ve said, mature industries or manufacturing-heavy sectors where there has been little domestic employment growth.

Indeed, if you have Fortune 500 companies in a hot industry, that can fuel extraordinary growth

I am not sure if your pun was intentional, but this explains a lot about Houston and OKC, and to a lesser extent Dallas. The oilfield is a boom-and-bust sector though.

Brookings runs the “Metro Monitor” (which includes all the ones we discuss here). Buried in their webpage is a chart of each metro’s Location Quotient for employment in various large SIC group.

What is striking about Cincinnati and Columbus vs. Indianapolis is that the two Ohio cities are overweighted in certain fields, including finance and professional services in both and manufacturing in Cincinnati, while Indy “looks like America” without a single industry-cluster LQ over 1.15. Link here: http://www.brookings.edu/research/interactives/metromonitor#/M17140

The groupings are not really fine enough to sort out specializations like “life sciences” or “advanced manufacturing”, since companies like Rolls Royce (jet engines), Dow Agro and Eli Lilly would be classified in “manufacturing”. But it is an interesting snapshot.

Re population growth: I can’t imagine Tier 1 metros (such as Chicago and NYC) growing at the same rate as a fast-growing Tier 2 (such as the sunbelt metros 1980-2010). The old life-cycle growth curve probably applies to metro areas: they reach a “mature” phase where growth levels out.

I agree with Frank: for such cities, it’s about the churn and the fact that an absolutely large number of people still “stick” in the large metros even though it is a lower percentage than some nominally fast-growing place. Adding a quarter-million people is adding a quarter-million people regardless of the starting base.

I think what Renn is ultimately trying to say is why isn’t Cincinnati more European?

The hills and the rhine were what initially attracted immigrants from Bavaria and is what makes Cincy beautiful today with the addition of the architecture.

But reading Witold Rybczynski’s “City Life”, you’re reminded that some of the great European cities are actually quite small. This is why I think locals are bothered by comparisons to automobile city and state capitols Indy and Columbus, or industrial South Side Chicago or Detroit.

Two comments. First, I have seen many cities called “river & hill cities” in this blog discussion. Cincinnati is different. Pittsburgh is as hilly. I hear San Francisco is as hilly. Other than that, I have never been to a major city that has more hills than Cincinnati. It’s not just hilly-its extremely hilly. Louisville for example isn’t even close in terms of hilly-ness. Never been to St. Louis or Minneapolis, but I can’t imagine they are anywhere near as hilly. Heck, all the northeast is hilly, but not like Cincinnati or Pittsburgh.

George, in Louisville the hills are on the Indiana side of the river, much of which is either floodplain or unbuildable until you’re pretty far inland (Harrison County where I grew up, for example).

Second, and perhaps more importantly, just because Cincinnati has many urban assets doesn’t mean it will automatically translate into economic success. It’s a beautiful city with a unique built environment, and that’s worth something. But it in and of itself will not transform Cincinnati into the next Austin.

In fact, you could say that Austin is the Anti-Cincinnati, a city which (I am guessing-not having been there) has a far inferior built environment. It’s a much younger city, and doesn’t have near the history. But it’s a boomtown. It’s a place where lots of outsiders come and settle.

As I said before, I briefly considered moving to Cincinnati, but decided not to when I realized that I would always be an outsider in the culture there. I couldn’t answer the “high school” question correctly. That’s the literal truth. I think it keeps some folks away.

Beyond that, Cincinnati needs something to leverage. The scenic beauty may leverage some modest influx of population and some tourism if handled correctly, but it will need a kick-starter to really boost it.

The problem here is that I’m not sure what Cincinnati’s kick-starter is. It has a lot of cultural assets, but what institutional assets does it have to leverage? Unlike Pittsburgh, it doesn’t have a major university presence. Yes UC is a big school, and it’s not to be ignored, but I don’t know if it and Xavier are in themselves big enough to leverage a whole regional economy. The Children’s Hospital is top notch, but IMO Cleveland and Pittsburgh have far stronger assets with institutions like Case Western, Cleveland Clinic, Pitt and Carnegie-Mellon.

You have some large Fortune 500’s, but as mentioned above, I don’t know that these are the kind of institutions that will jumpstart growth. P&G does lots of product research, but much like Battelle in Columbus, they aren’t the kind of institution that will foster new tech start-ups by the dozens. Krogers is a great Blue-chipper, but it is what it is. Same with Fifth Third Bank.

Finally, Cincinnati is suffering the same fate as most mid-sized metros with the severe downsizing of the airport. I think this is an under-appreciated negative for all cities in the Midwest not named Chicago or Detroit. Chiquita left town and that was cited as a big reason.

So in addition to more openness to transplants, I thin Cincinnati needs an economic spark to bring some new life to it. I don’t know what that is, but if it could find it, the city could potentially fulfill its vast potential.

On the plus side, GE just announced that they are opening their new global operations center in Cincinnati. While this is more of a high-end back-office operation, perhaps (if it becomes more open to outsiders) Cincinnati can position itself as a better alternative to the number of other cities that are attracting similar operations. Why go to Columbus, Indy or KC when you can get similar costs and a much more beautiful and interesting cultural and built environment in Cincinnati?

Aaron, I believe that. Many places have hills NEAR the city. My hometown of New Haven has two 900+ foot sheer cliffs the northeast and northwest. that overlook the city to But Cincinnati is one of the few cities built directly ON those hills and it has a definite impact on how you experience it. My guess is that

@ George Downtown, OTR, West End, Camp Washington, Northside, Covington, Newport are all in the basin. The “bowl” of Cincinnati was what was first settled and people moved up the hillsides (Clifton, Walnut Hills, Mt. Adams, Price Hill) when the inclines were built. The seven hills are complete or partially defined city neighborhoods.

Eric:

Yes I am familiar with that. Many cities I have seen have avoided or built around their hills. As I mentioned, Pittsburgh and San Fran are notable exceptions.

I think it’s a fairly unique trait to have hills developed as neighborhoods. IN my before-mentioned New Haven example, these two hills are parks. They are beautiful in their own way, and great assets, but having hills developed and integrated as neighborhoods into the city is one of Cincinnati’s aspects that I think is truly unique.

The other thing about Cinci is they are larger hills. Perhaps only Pittsburgh has bigger hills that have been developed. It’s not just rolling land. Lost of places have some rolling areas that are developed. Only a few have steep hills that provide breathtaking views like Cincinnati.

In all my years living and working here (since 1988)…I have never been asked where I went to high school. Not saying it does not happen, but it seems overblown. Yet, here I will defend it a bit.

Schools here are unique, a very high percentage of students attend private schools; Catholic, Protestant, & secular. Even some of the magnet public schools feel like private schools. There is even a sports league, GCL…Greater Catholic League that spans here and Dayton. Very few people attend K-12 with same people. Many go to elementary at a private school or public montessori, then flip to public for HS. My friend’s son went to St X, but could have gone to Elder HS or Roger Bacon HS or Walnut Hills (or any Cincy Public ‘magnet’), Western Hills, Clark Montessori or Cin Christian Hills…or Seven Hills or Cin Country Day. Perhaps literally 14 choices (or more).

So there is much meta-data in the HS answer:

Walnut Hills HS – not geographic save for the city of Cincinnati, 98% chance you went on to college, public, very college prep, there are even NKY kids paying tuition to attend

St Xavier – private catholic, most likely north-west, but being Jesuit makes it less geographical, all male

Moeller – private Catholic, East side, all male

Elder – private Catholic, West side, all male

Roger Bacon – private Catholic CoEd

Seton – private Catholic, West side, all girls

St Ursula – private Catholic, East side, all girls

Seven Hills & Cincinnati Country Day – expensive, small ,private, secular, parents probably in .1%

Taft, Withrow – local urban neighborhood schools, they struggle in testing/funding etc

School for Creative & Performing Arts – public magnet, self-explanitory.

Indian Hill HS – public, chances are your parents are the %1, geographical

Wyoming HS – public, chance are your are parents are the %3

The same pattern is in NKY. So I think the HS question gets an unfair rap if you are not familiar with the local dynamics.

I heard at one time 50% of the Cincinnati PD went to Elder. Is this conjecture or true. What happened to Purcell-Marian?