[ This week Eric McAfee takes a look at phenomenon that is on the rise in America today – suburban blight. Early generation suburbs across America are falling into decay, bringing with them all the ills we have traditionally associated with the inner city. Eric highlights an example for us in Kansas City – Aaron. ]

Over the past century, the word “blight” has undergone a curious expansion in its denotations. It was originally a botanical term referring to a disease characterized by discoloration, wilting, and eventual death of plant tissues. In contemporary parlance, however, I suspect a far greater number of people use the term in combination with “urban”–a metaphoric reassignment of the characteristics that organic plant matter can suffer, only this time applied to non-organic human construction. So urban blight appropriates characteristics of plant disease but in a sociological form, in which the tissue of a city suffers dilapidation, underutilization, or outright abandonment. In contemporary life, it’s hard to imagine and definition of blight without at least some reference to urbanism; such is the case with Merriam-Webster and Dictionary.com at least.

Anybody getting this far in the essay is probably well familiar with urban blight, not just as a label for a certain condition but its physical manifestations. But does blight always have to affect urban settings or the inner city? In the last 25 years, a new type of blight has emerged in America, affecting post-war, automobile oriented, outer-city districts. It requires little semantic stretching to call it suburban blight; I can think of no more appropriate label, since it is characterized by the same disinvested conditions that urban America experienced half a century ago. But does it ever look as bad? After all, we don’t typically associate a three-bedroom house – with a big front yard and an attached garage – with decay or neglect.

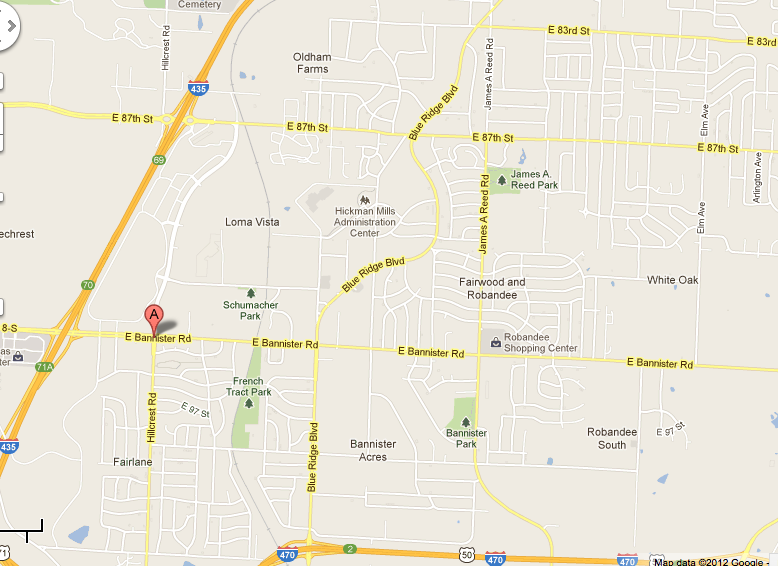

While I’m sure there are plenty of other, more persuasive examples, Kansas City offers the best visual evidence I have ever seen that serious blight can afflict the suburbs in equal measure. The Bannister Mall area, about 12 miles south of downtown KCMO but still within the city limits, was a flourishing retail and residential corridor as recently as 1990, but it took a significant turn for the worse later that decade. As dead malls go, it’s a well-known one: websites like Labelscar and Dead Malls chronicle the one-million-square-foot mall’s downfall (first opened in 1980) in great detail. Needless to say, it follows similar patterns seen in metros across the country: a decline in the desirability of the apartment complexes in the area forced many of them to cater to a lower-income population. This influx of Section 8 tenants, in turn, caused an uptick of crime in the mall by the mid-1990s, scaring away shoppers. By 2000, the first of the major anchors closed; over the next six years, the other three department stores followed suit. For a few of those years, the mall managed to hang on with mom-and-pop in-line tenants. But these local businesses only chose to locate at the mall

because of significantly lower leasing rates, and by that point the mall was already over 50% vacant. The meager revenue proved insufficient to cover expenses for such a large structure, and by spring of 2007, the Bannister Mall closed completely. Various developers floated proposals for the site, the most lucrative of which was a sporting complex for the MSL Kansas City Wizards, combined with office and retail. A Tax Increment Financing (TIF) proposal helped to generate the funds to demolish the mall in early 2009, but the national economy had soured enough by that point that nothing further has materialized.

The remainder of this essay explores the current conditions of the area through an array of photos–not just the Bannister Mall, but also the extensive regional shopping cluster that once surrounded it. It is a grim site to behold these days. Here’s what the Bannister Mall looks like today:

The east side of Hillcrest Road doesn’t look any better. Some might argue that it looks worse: it includes several independently operated strip malls tethered to big-box anchors, the vast majority of which are completely vacant.

With an unusual combination of bold colors and a formidable size, I cannot guess what tenants this big-box contained two decades ago, though a Google Streetview suggests, from a handful of cars in the parking lot, that was still marginally occupied as recently as September of 2011. Across the street, an isolated big box shows traces of life, evidenced by the few cars parked at the far-right margin of the photo.

But, upon making a u-turn and reverting southward along Hillcrest, another strip mall on the west side of the street (the same side as the former Bannister Mall) is so derelict that all entrances have been blocked off.

After continuing southward to return to the Bannister Mall site where Hillcrest intersects with Bannister Road, the sign for one other prominent retail pokes up above the slope.

Yes, Bannister Mall and its ensuing suburban blight is a byproduct of white flight. Similar life cycles first emerged all over America in the 1950s, leaving impoverished urban inner cities in their wake. Meanwhile, the earliest suburbs, preferred destinations of the emergent post-war white middle class, are now routinely showing their age. All too often, their demographic profile is similar to the inner cities, but with a determinedly auto-oriented suburban appearance. For those of my readers in Indianapolis, the 1990s trajectory at Bannister Mall eerily parallels what happened in the Eagledale neighborhood and Lafayette Square Mall over the last twenty years. (I blogged about Lafayette Square in the same article where I explored Burlington Coat Factory, which–surprise!–is a tenant at the aforementioned dying Indianapolis mall.) In both Indy and KCMO, these auto-oriented districts fell within the city limits and fed into their already declining public school districts. The housing in Indianapolis’ Eagledale is almost identical to that in the Bannister Road corridor of Kansas City.

But the economic forecast of Lafayette Square and Eagledale still seems nowhere as bleak as that of Bannister in Kansas City, at least to me. Not only is Lafayette Square Mall still hanging on (though hardly flourishing, with about 50% vacancy), the sundry strip malls and big-boxes around it are surviving as well. None of them are thriving, and national chains have largely fled Eagledale to the suburb of Avon, just as they migrated to Lee’s Summit outside Kansas City. But the Lafayette Square district has hosted a huge variety of immigrant entrepreneurs, and now the area is known for its ethnic supermarkets, taquerias, hookah cafes, and restaurants catering to a few dozen different non-American cuisines. The city is teaming with the Department of Public Works to re-brand the area as an international marketplace. In addition, an emergent artist community has taken advantage of the cheap rents and leased an old Firestone outparcel near Lafayette Square, turning it into the Service Center for Contemporary Culture and Community: a performing arts space, library, community garden, and art gallery, taking advantage of the area’s eclectic demographic mix. Eagledale in Indianapolis may no longer be a middle class neighborhood, but it doesn’t look like the aftermath of a nuclear holocaust.

The Bannister Mall site has stumped developers and city officials over the years, since southeast Kansas City in general seems to be evading any sort of organic re-invention. I suspect that Kansas City, generally a prosperous metro area, has its own immigrant-influenced equivalent to Lafayette Square/Eagledale in Indianapolis, but the old Bannister Mall certainly isn’t it. This variant on socioeconomic blight poses a wicked challenge. I’m not holding my breath for the hipsters or the gays to colonize it, the way they are in some of Kansas City’s formerly dying old walkable neighborhoods closer to the central city. And the yuppies won’t come in later to gentrify it either. The blight that afflicts Bannister and Hillcrest Roads has yet to reveal a treatment.

This post originally appeared in American Dirt on November 30, 2012.

I’m pretty sure that the large building with the bright colors was a HyperMart. There was one in Topeka that looked just like it. HyperMart was kind of the first version of WalMart’s Super Centers I believe.

The bold red and blue building is a Hypermart. It was Walmart’s early experiments with department stores that included groceries and other small retailers near the entrances. Eventually these became Super Walmarts or Walmart Super Centers. I grew up in Kansas, about 2.5 hours west of Kansas City and remember taking trips to the Hypermart in Topeka.

http://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hypermart_USAhttp://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hypermart_USA

Interestingly, though, Walmart built a NEW store just north of the dying Lafayette Square Mall in recent years, probably because the area is served by two exits from I-65, 38th St. and Lafayette Rd.

As pointed out, the cheap housing and cheap commercial space in the Lafayette Square/Eagledale of Indianapolis has attracted immigrant entrepreneurs.

Learning how to deal with these issues is one of the reasons I work in an early auto-centric suburb. “We” (urbanists and community development professionals) have something of a recipe book for bringing back urban neighborhoods blessed with solid historic buildings, sidewalks, trees, alleys, transit and close proximity to the urban core.

We’ve got to figure out the solutions to decaying early sprawl.

I wonder if this area of South KC should do what parts of Detroit are doing: revert to farmland. Or, why not make it a park? Why bother with redevelopment—just bulldoze the lots and plant thousands of trees. Or bulldoze it and offer it to urban farmers.

There are similar (though arguably smaller) pockets of blight in the NYC suburbs where I grew up. The most notable is probably a former Grand Union that has sat vacant for at least 10 years, which has virtually killed the strip mall it resides in (save for a doctor’s office, a pharmacy, and possibly a vet).

As a current KC resident and one who grew up in this exact neighborhood, the negative transformation of the Bannister area vs. the congruent positive transformation of the urban core are what some are calling the “Europeanization” of Kansas City.

When I was growing up as a child/teenager, the Bannister neighborhood was one of the most saught after areas to live, work, and play in the metro. Where I live currently (a neighborhood near downtown and the 18th & Vine district) was dillapidated and abandoned. Fast forward 15 years later, and now Bannister is having a hard time redeveloping while the neighborhood I live in, once abandoned, has dorms, a grocery store, and $250k plus homes being built/refurbished at a rapid pace.

KC might be one of the best examples of a mid-sized city quickly advancing into America’s new stage of urban/suburban development: Urban-Elites/hyper high-end redevelopment in the core, challenged/dillapidated neighborhoods in the inner-ring suburbs, new construction/”new money” in the exurbs, agriculture in the hinterlands.

A fascinating turn of events as one who has literally been a part of/witnessed this transformation first hand. Thank you for this article! Excellent work!

P.S. – That building was a “Hyper-Mart”. The employees used to wear roller skates because it was such a large space (not a joke)…

Thanks for the comments, everyone. Tim Lacy, the commercial strip seen here consists of probably at least a square mile (possibly closer to two) of virtually complete vacancy, save for the inevitable Burlington Coat Factory and K-Mart. However, to the east and south are largely intact neighborhoods with housing from the 1950s and early 1960s. Most of it is occupied, though hardly in prime condition. The area remains reasonably densely populated; it’s the income density that has dropped precipitously. And, of course, in time, the population itself will continue to decline.

Chris, I’d say Lafayette Square and its environs have a much, MUCH brighter future than Bannister in KCMO. And I obviously pointed this out in the blog, but it seems like the equivalent area in Indianapolis has attracted the sort of postmodern, anything-goes micro-investors that strive to romanticize the banal–a postmodern gesture in itself. This is exactly what these sort of landscapes need.

The big store was indeed a Hypermart. When Walmart moved a short distance away it was with a financial incentive to do so. Virtually every change that KC resident urbangent refers to was done with a tax incentive from the city. The overall effect has been negative.

Tax incentives for development, or what Mark Funkhouser is referring to, re-distribution of development, is up for debate as to its positive or negative effect. From my point of view, its simply an adjustment given current market demand (i.e. – urban density) vs. mid-century quasi-suburban development. That said, I somewhat agree with Tim Lacy: this land can be properly converted to ag and/or parks with investment from public funds. All in all, it is clear that market forces are pushing people into the urban core and the exurbs (in KC and most other markets), for better or for worst, the cities that will win this next round are those that think of creative solutions to deal with dilapidated inner-suburban neighborhoods. Tim Lacy offers up one of many possible solutions….

The dead Bannister mall is bordered on one side by interstate…a common-enough placement in the Midwestern cities I’ve driven through. In studying aerials, though, there is a river corridor and hundreds of acres of vacant land or sand/gravel strip-mining on the other side of the interstate. This only exacerbated the lack of density and the quick change of the immediate area: as the residential properties (to one side only of the mall) moved downscale, the river corridor didn’t provide an anchor of more-stable, more-desirable neighborhoods as it hadn’t yet evolved into a former-gravel-pit-turned-lakefront higher-end residential area. Eric, contrast this with the White River corridor from 75th to 146th in Indy and Carmel…the 1,3,5 mile markets for two suburban malls (Castleton and Keystone Crossing)…and even the position of Lafayette Square 3-5 miles or so from higher-end development along Eagle Creek and White River.

Retailers tend to look at 1, 3, and 5-mile demographics, which leads developers to do the same. Both corporate communities chase high incomes to the edge of development. Edge cities desperate for commercial tax base (in places where the local tax system is based on either property value tax or sales tax) offer active or secondary development incentives. There is no incentive to end incentives, so the chase continues unabated.

Counter-incentives are probably needed, but all the government assistance risks ever-tighter ties between local politics and local development based on a transactional model. This has questionable long-term social implications.

Chris, there is one incentive to end incentives, the fact that they are money losers in the end. Incentives worked in the past because they effectively transferred the money that bond holders or state and federal govn’ts had paid to local governments in turn to developers. It didn’t matter that this money would never be recovered, because the first generation residents and businesses would be gone by the time things had to be repaid. With housing credit and money for public infrastructure much tighter and stagnant property values, the current residents of exurban areas don’t have the same expectations that they can escape the future finances of their areas by selling out for more than they paid and moving somewhere else to do it all over again. incentives will die a slow death as more and more peopel come to realize that they are at best a neutral for their areas.

Suburban blight in Kansas City?

But wait. Kotkin and Cox at Newgeography says everyone is in love with suburbia.

It’s hip. It’s in.

http://247wallst.com/2013/05/28/cities-where-suburban-poverty-is-skyrocketing/2/

Racaille, keep in mind that suburbs have the majority of the people, hence they will have a lot of poor people as well. Poverty rates remain higher in the city, though clearly some inner ring areas (especially those adjacent to unfavored parts of the city) are really struggling.

“Poverty rates remain higher in the city”

Yes, but in two years that will change.

http://www.dallasnews.com/news/metro/20130520-poverty-surging-in-dallas-fort-worth-suburbs-more-than-inner-cities-study-finds.ece

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/05/21/opinion/cul-de-sac-poverty.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0

The problem with so many urban planners/pontificators is that they are stuck on this idea of quantity equals quality.

I call it the Cheesecake Factory syndrome. Where one gets huge quantities of mediocre food and resulting intestinal distress for very little money.

Matthew, I disagree. For any single edge city, there is no disincentive to max out the credit card for new infrastructure and development incentives. After all, the next town in has the aging pieces and parts, and retiring firefighters and police. New cities don’t have that, and “need” tax base, particularly commercial/retail.

Absent a couple of major suburban defaults, I don’t see anything structural happening to interfere with the marginal value of incentives for any particular municipality.

Well written article. As a person who does layouts, annual reports, etc., I just want to encourage you to get better shots for your articles and improve on the composition to capture the reader’s attention. Many of the shots are 50% sky which seems to be a leading cause of the subject area being under exposed. There are also several shots where the buildings are tilted in the shot. Through cropping you can get rid of the excess sky but you would still have the exposure issue. With the day being heavily overcast you also would benefit from a UV filter or wait for a better day to get contrast and brighter colors. There are photo software programs that can stitch photo together or slightly rotate a picture.

Best wishes on you future photo shoots and articles.

Thanks again for all your comments. Chris, I can’t tell from your recent comment if you’re disagreeing with me, but you’re absolutely right that the areas surrounding Lafayette Square include stable or even high-income areas (such as Wynnedale) to offset the lower income Eagledale whose downturn in the 90s helped seal the fate of Lafayette Square. Contrast that with Kansas City’s Bannister Mall ruins, which include many, many more neighborhoods of the age, style, and income level characteristic of Indy’s Eagledale. Those neighborhoods, which stretch forever to the south and a little ways to the west in Kansas City, are more or less in the same condition as Eagledale, if not worse. Eagledale is tiny by comparison.

Craig, thanks for the input, and I’d never deny that most of my photos aren’t very good. However, I took all these pics on a Fuji Finepix 10 megapixel that I ordered for its durability, because my old camera bit the dust (literally) in Afghanistan. Half of these pictures I took through my car’s windshield because I only had about 35 minutes to spend on site–and I had only read about Bannister so I didn’t know what to expect. I never knew before I visited that it would turn into a blog topic, and because I had to get to St. Louis that night, I didn’t really have the option of waiting for a better day’s weather. To be frank, I also cannot focus on composition like I should because I have to take the pictures in a hurry, either because of personal safety or, quite frankly, a person going around taking pictures in a desolate environment like this often looks suspicious to city workers. (I’ve been escorted out of the aforementioned Lafayette Square Mall for taking photos.)

If it sounds like I’m making excuses for the quality of some of these photos, well, I suppose I am. I hope that the writing and analysis would be what captures the reader’s attention, and he/she will recognize that mediocre photos are merely there as a supplement to the writing, because I’m not a photographer, nor do I promote myself as keeping a photography blog. Maybe someday I’ll try taking great pictures, but more often than not the act of shooting a photo is more of a passing fancy that later provides material for an analysis. I definitely appreciate your advice, and when I start making money again here later this summer I’ll probably invest in a (slightly) better camera.

Eric, I’d say I’m offering additional factors for analysis, looking for telling differences through contrasting observations. I applaud your deep-dive analyses.

We all understand that there are dead malls out there, but also living (even thriving) ones and lots in between. I shy from the assertion that “(all) malls are dead”…which you do not make, but which many aggressive urbanists do.

Turning a dead mall into a greenbelt is an extreme remedy…not impractical or without merit, but extreme. It’s probably the last resort for a worst case, which Bannister may represent.

As with politics, all real estate is local. I think some deep analysis for each dead or dying mall is the appropriate approach. I have highlighted Lafayette Square partly because we’re both somewhat familiar with it, because it’s not a extreme case like Bannister, and because it represents a somewhat natural/organic/market solution. Heavy interventions there may not be necessary.

This is an interesting topic and one that I have consulted on professionally in the Midwest — how to revitalize, redevelopment, or reuse dead or dying malls. For many of the sites, there is no private market solution — the sites are simply uneconomic to redevelop without significant public assistance. The sites may continue to remain in some low-grade form of use, but this in nearly all instances is a step on the way to eventual abandonment and tax delinquency. If the site is located in an area where there is reluctance by the public sector to become involved, then the the blighting influence of these sites on neighboring properties and neighborhoods can come into full fruition.

I think the exception to the full blown blight cycle tend to be places with either very high property values (I’m thinking of a closed Target store in the Seattle area selling for $25 million) or with very high population growth rates. There is no profitable way to turn these sites into urban farms, recreational fields, etc. In slow growth areas, it will probably take a decade or two of planning, significant public investment (for demolition and environmental cleanup — which can be significant even at these sites depending on their age), elimination of the overhang of vacant commercial space (that drives down lease rates to the point where new development in not economic), and then some type of repurposing and further significant public investment such that the area will have some attractive amenities that may eventually be enough to attract private investment. Reuse for retail in many instances won’t occur, as newer better malls have already been developed elsewhere in the metro area.

I think that this type of problem in various forms is the destiny of many, if not most of the boom cities, of the past two decades for which the growth was characterized by massive mediocre quality sprawl. These areas when new, seemed attractive and modern, but tend to age quickly and become increasingly unattractive when they reach 30 or 40 years old. Then many are exposed as ugly, low quality, poorly planned areas, that require significant investment beyond what makes economic sense. How do you fix an area that doesn’t have attractive features, walkable neighborhoods, and efficiently laid out street system, etc. Cities that maintain high growth rates may be able to mask the problems of these areas for a while (there may be enough demand for new housing that the private market and developers may acquire and redevelop the sites before a protracted period of disuse and blight occurs). But I’m not sure that this is working very well in even some of the highest growth rate cities such as Dallas or Houston, if you look at the declining population and disinvestment that is occurring in the areas outside of their downtowns.

On a more positive note, in a somewhat similar area in northwest Milwaukee (the former Northridge Mall), transactions for three large vacant retail properties have occurred within the past 2 to 3 months. The 900,000 square foot former mall itself was acquired through a court action (the property was in receivership) by a local spice distribution company (Penzeys Spices) that for repurposing the building and site for use as the company’s distribution center. The acquisition price of $700,000 (combined with $800,000 spent in efforts to acquire the property), still represented a significant discount to the $6 million paid by the second group that acquired the closed mall in 2008 with plans for redevelopment. Penzeys will reportedly invest $10 to $15 million in the conversion effort, which includes 60 acres of land.

A recently vacated 133,000 square foot former Walmart store located across the street from the Mall is being purchased by an automotive transmission rebuilding company (a second “retail to light industrial” land use transition). The third site is a vacant 140,000 square foot Lowes one mile to the east of the Mall (and former Walmart) that is being redeveloped by Walmart as a new supermarket and discount store. This conversion is actually a surprise in that the former Walmart store had already been replaced by a new store located elsewhere in northwest Milwaukee. Walmart apparently changed its mind about the ability of the new store to serve this area of northwest Milwaukee. The former Lowes store however is located in a more desirable neighborhood (even if only one mile distant). Although the Mall has been largely vacant (and a significant blighting influence) for nearly a decade, the sale and repurposing of the two big box stores has been surprisingly rapid in a slow growth city in what remains a relatively distressed neighborhood.

The failure of a metro to contain the externalities of local incentives will be corrected harshly by the detroit style collapse of the metro. There may be no disincentive for individual municipalities or townships to offer incentives, but the negative externalities for the metro mean that the right reorganization of local and state government policies can work against them. There are countless ways in which high cost or denser locations can undermine incentivized develoments and discourage new ones. Cost-sharing, tax-pooling, coordination of transportation, sewer, water, police, etc. State policies preventing the use of state money for local governments to incentivize and the increasingly wariness of municipal bond buyers will all work against local incentives in the future.

But Matthew…the densest, urban part of the Detroit metro is what has lost people and business and vitality. Detroit, not Grosse Pointe nor Royal Oak nor Farmington Hills, nor Ann Arbor. The metro has not collapsed. Only the old city. For only the old city (in any older metro) has the accumulated burden of too much infrastructure to maintain, too little revenue, no expansion potential, and a huge pension and retiree healthcare burden.

That proves two things: sprawl can apparently continue even as the central city dies, and you CAN be a suburb of nowhere.

Detroit is the opposite of your argument. Unless you are imagining that MIchigan will create a “Detroit Metro” government as a result of the city’s bankruptcy?

Again: there is no market (or regulatory) mechanism to prevent the next local incentive package anywhere.

Chris,if what happened in Detroit could happen everywhere in the U.S, why hasn’t it? How has every other metro done a better job of containing externalities than Detroit? How do The Loop in Chicago or Pittsburgh, much less the burgeoning downtowns of Atlanta or Denver exist, and thrive, if the inexorable forces of disintegration evident in Detroit are actually present everywhere. The forces of externalities are self-evidently not unopposed in the world. Something happened in Detroit that just hasn’t happened in other places.

Lots of good comments back and forth here but the last point made might be the most important: Something happened in Detroit that just hasn’t happened in other places. What is that something? And, I would add that, although it hasn’t happened yet, it can and so it is important to understand it.

Too quick a trigger. “Anonymous” is me, Mark Funkhouser

You don’t think that Detroit stands alone with respect to disinvestment and absolute economic decline in the U.S? I realize that contrarianness is popular on this site, but I just don’t know how you can disagree with that. Even Cleveland an Buffalo, the honorable mentions of metro failure, have performed vastly better over the last several decades.

Mathew, I’m agreeing with you. I do think it probably stands alone at the moment. I’d like to know how that occurred. As you say, it IS important to understand it.

Let’s not forget Pittsburgh, losing population decade after decade 1950-2010. That was the benchmark of urban collapse until Detroit in the last decade and a half.

But this post is about suburban blight, not urban failure. Do the two phenomena have similar causes? Similar solutions?

The bulldozer was the solution-of-the-day when urban cores decayed. Is that also the solution to decaying suburbs and their “downtowns” (suburban malls and strip malls)? One key factor, to me, is durability and adaptability of construction.

In downtown Indy, a developer figured out a way to re-use a “modern” brutalist (poured concrete) bank processing center as the pedestal for a low-rise mixed-use development. Could multi-story concrete or steel-frame department-store spaces in dead malls be re-purposed for senior housing, healthcare, or mixed-use development?

Interesting observations one and all, especially since Detroit is unique among major metros for having experienced such a collapse. Other municipalities have suffered in equal measure–from what I’ve seen, Camden NJ, Gary IN, East St. Louis IL, all come to mind–but obviously there cities are inextricably tied to their larger metro areas. Pittsburgh is unique in a different way, in that the city has retained many stable and viable old neighborhoods within its limits, yet the metro has struggled tremendously, manifested through numerous smaller single-industry suburbs that have lost 80% of their population. McKeesport is among the larger of them, and is just as devastated as Gary or Camden.

Chris, I see what you’re saying in terms of Kansas City and its context. I’m not saying you’re recommended the greenbelt conversion, but it’s certainly an idea. Though my knowledge of KCMO isn’t as extensive as I’d like, I still don’t know if that would be a good idea. Kansas City is among the least densely populated cities in the country and is probably #1 in the Midwest. It has a well-celebrated park system–though it may be more in terms of quantity rather than quality, since I’ve heard the enormous Swope Park is perceived by many locals as too dangerous to visit these days. That said, all that parkland–much of it barely used–only further thwarts chances to add density to a city that needs it. I hope the leadership in KCMO devises something better than the expansion of a land use which the city might already have in overabundance.

At this point, Eric, probably suburban office or office/distribution space would be the “highest and best” use, since the arterial infrastructure would support it. According to Google Maps, Sanofi-Aventis has (or had) a facility just a mile south.

I generally agree with you that more greenspace in a low-density metro is not a good use. The widespread provision of public parks is an artifact of densely-populated, industrial dirty cities. In a city of suburban half or quarter-acres, there is abundant private greenspace and tree canopy.

Since there appears to be a limestone or sand/gravel mining operation a few hundred yards west, maybe Martin Marietta would want to mine the site, then turn it into premium lakefront land for development. 🙂

Chris Barnett,

The former Sanofi-Aventis facility now houses office space for Cerner, the world’s largest medical technology/records corporation, headquartered in Kansas City. All is not lost….

Nice debate, folks. I do think the jury is still out on whether Greater Detroit indicates that you don’t need a “there” there. Have spent a lot of time in the Detroit suburbs, and while many are doing ok right now despite Detroit’s problems, I do think there’s a risk of long term repercussions that we haven’t spotted yet.

I don’t think there’s any question of the retail suburban blight that you’ve documented–like you, I have seen no shortage of corridors like this all over the nation. The sleeper issue just behind it, though, is the neighborhoods around these corridors like the one you describe in the comment above. When the older residents die or have to move on, there’s going to be an even more profound impact on these communities–in many cases, there’s going to be almost no demand for those properties because of oversupply, because of their characteristics and because they were typically built kind of crappy to begin with. We’re seeing this developing all over the Midwest–it’s the same fundamentals that drove the reinvestment you’re seeing in the commercial space, but with hundreds or thousands of tiny priorities and individual owners. We have to get a lot better at fostering land use change and reinvestment, and we gotta do it yesterday.