The is the last in my series on reconnecting Chicago with its natural city-region in the greater Midwest. But it really has nothing to do specifically with Chicago, or even the Midwest. It deals, rather, with innovation generally.

I discussed how companies were outsourcing offshore, with a big driver being labor arbitrage. But as with all trends, labor arbitrage contains within it the seeds of a successful counter strategy. That counter strategy is innovation.

It’s been noted before that industries with access to large quantities of cheap labor tend not to see productivity increases. There is simply no driver for it. We see this here in the offshore trend. I look at my own technology industry and can’t help but noticing that there appear to have been few if any basic improvements in productivity over my 15+ years of experience in mainline software development. That is, it still more or less takes the same number of man hours to develop a given piece of functionality as it did back in the day. And this is after multiple generations of technology. There have been cost reductions to be sure, but those have come via things like labor arbitrage and hardware cost efficiencies, not reducing man hours.

But as we’ve seen the rise of offshore development, we’re seeing something interesting happen on shore. As onshore talent suddenly found itself operating at a distinct cost disadvantage versus offshore, that cost pressure brought innovation to the way software is developed, which in turn has led to radical reductions in cost and speed to market for certain classes of software. This has been driven by two basic items: open source software/cloud computing and a new agile methodologies.

The first item has more or less made it free to start a software business. You no longer need to worry about expensive software licenses, hardware purchases, or hosting fees. Your entire technology stack is open source software available at zero cost. And you can host your application for next to nothing on a service like Amazon’s EC2. Whereas even a few years ago starting a software business almost required some level of outside funding, the raising and deployment of which sucked up huge amounts of management time and came with unpleasant strings attached, now the basic environment is more or less free.

The second is about a whole new way of writing software, one that is about small, talented teams who work closely with the end user of the software to rapidly create products and refine them over time. It uses new development frameworks like Ruby on Rails; new agile, iterative development processes that focus on delivering more of what you want (i.e., running code) and less of what you don’t want (i.e., paperwork and feature bloat); and a new staffing model built on high-skill developers who also have the people skills necessary to work directly with customers and users. This is a killer combination, perhaps best exemplified by its chief exponent, Chicago development shop 37 Signals. They literally wrote the book on this – their “Getting Real” is an absolute must read for anyone in the field, as is their blog “Signal vs. Noise“.

This 1-2 punch is revolutionizing software development, especially for software as a service and for departmental type applications. I wouldn’t be surprised to see it completely displace traditional approaches for these classes of apps in coming years. This shows that the rise of offshore software development does not necessarily mean the end of the onshore developer. It only forced those developers to get creative and innovate. (I should note, it also disrupts the venture capital model, since people wanting to launch software businesses no longer need to beg for money to do so. They can look for funding only when they need cash to scale a proven successful business – and will have much more negotiating leverage when they do so).

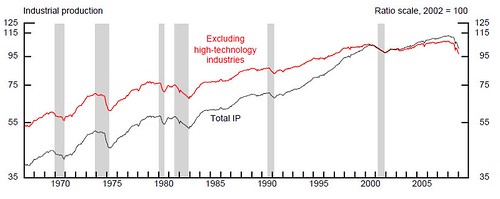

This isn’t only true in the software field. We’ve also seen it in the manufacturing space. The collapse of employment in the manufacturing field in the Midwest is not primarily the result of production moving offshore. Rather, it comes from onshore productivity improvements that resulted from low cost competition. That competition forced onshore companies to innovate and get lean and mean. The United States is in no danger of not making things any more. Far from it. Until the onset of the recession, which is crimping output worldwide, the United States continued to set records for industrial production year and on year. Here is a graph from the Federal Reserve:

Shaded areas are recessions. Click to enlarge.

The Midwest produces as much industrial output as it ever did. Even in the 2000’s, non-high tech production has held its ground in America. It just does it with far fewer workers than it did in the past. That’s a key challenge facing the Midwest. It’s not that it can no longer make things or grow things, but that these no longer require large number of unskilled workers to do so. It’s just the same with the software development example I gave previously.

Innovation doesn’t necessarily solve the employment challenge, but imagine where we would be without it? It would be game over. Granted that it doesn’t solve all of our challenges, it does show that America and the Midwest can compete in the innovation game when forced to. Much of this manufacturing productivity gain has taken place in the Midwest. And as I noted, 37 Signals is based in Chicago, making the Midwest an epicenter of the new software business model.

I believe that this shows the future generally. There won’t be as many plants employing thousands. Rather it is going to be a large ecosytem of smaller, high value added businesses that in aggregate add up to a lot of jobs. I again think of the motorports industry in Indianapolis. This cluster has few individual large employers, but collectively employs north of 8,000 in the metro area with high average wages. This is the model of the future, and the Midwest has to figure out how to adapt to it.

So how do we do that? How do we become a more innovative economy? As many have noted, the Midwest has been low on innovation for some time. It had big ideas back in the agro-industrial awakening in America, but then became content with what it had. Over time, it lost those innovative fires and became not just unable, but in a very real way unwilling to change to adapt to changing times. Even Chicago I took to task in the setup to this series for simply riding the trends rather than defining what it means to be a successful city properly so-called in the 21st century. Becoming once again a locus of innovation is key for the Midwest to survive in the future.

Easier said than done perhaps. How do we get there? What holds us back? What are the barriers to innovation? I have some thoughts on this to share.

Firstly, let me say that perhaps counter-intuitively, what might seem the hardest part of innovation – coming up with new ideas – is actually the easiest part. I continue to be amazed at the quality and quantity of the good ideas I run across every day here in the Midwest. The real question isn’t why don’t we have any good ideas to try, but why don’t we actually try them. This to me is the key challenge to solve. There is no end of people out there selling innovation methodologies trying to help people become more innovative. Clearly people recognize the innovation imperative. But the problem isn’t ideas, it’s bringing those ideas to reality. This points us in the direction of the real problem place. It’s not innovation per se, but the barriers that keep innovative thinking from finding its way into practice.

Beyond just the simple fact that people don’t like change, a not insignificant point, here are some things that tend to act to hold us back from realizing innovation. To build an innovative business, city, or region, these are the problems that need to be looked at and figured out.

1. The risk paradox. As a contrarian sort of guy, I’ve said before that we should invert the world. Our strengths are our weaknesses, our weaknesses strengths. In this context, to the extent that we are already successful doing things one way, it creates an enormous barrier to us doing things a different way. Whereas, if we are already failing, the cost of trying something new is much lower. People talk about building on assets. But though assets are good to have, they also hold us back. Cities and companies defend their existing businesses and assets if they have them instead of figuring out what they need to do to be successful tomorrow and the next day. They make decisions they would not be making if they didn’t have success to defend.

It should be no surprise to hear the anecdotes of successful entrepreneurs who started businesses after losing their job or going bankrupt. These people had less to lose than the guy who would be quitting his six figure position to start a risky endeavor. ROI is return on investment. But investment is not fixed. For someone who has to give up something successful in the present to undertake something risky, part of the investment is what you are giving up. This means the return needs to be that much higher to justify the risk, creating a structural barrier to entry to the new and innovative for the successful.

I don’t know that this problem can ever be solved since it seems to be fundamentally rational. However, I think we can change the culture to remove the stigma of failure and also to figure out how to encourage those who are in plainly untenable positions to be willing to change. It strikes me that it generally takes a catastrophic loss to get people to change their ways. Slow decline doesn’t seem to do it. People like to try to cling to what they have to the bitter end. Again, it is not surprising to me to hear so many people who found religion say that they “hit rock bottom” before they turned to God. It seems to only be in these desperate situations that people are willing to try going in a different way. Why is that? I wish I knew. So many small manufacturing towns in the Midwest need radical changes in public policy, but only a handful of them show any signs of doing so. I think it is notable that it is Youngstown, which was completely ravaged by the collapse of the steel industry, that decided to think the unthinkable and embark on a planned shrinkage plan. Again, it was Pittsburgh, a city that lost practically its entire industrial base, that dared to go off in a new direction. If only we could get places to see the value of a different way before it came to that position.

2. It takes a village (or at least a team). Having an idea is only one part of what it takes to make it real. The skill of having ideas is distinct from that of bringing them into being. I continue to see small companies started by small teams of four people. That seems to be about the right number needed to bring the right blend of skills – technical, organizational, operational, sales, financial, etc – needed to create a real business. If the guy with the idea doesn’t meet like minded people with complementary skills that he can trust and who are likewise interested in doing something with it, it can die on the vine.

The same thing is true inside organizations. Having an idea doesn’t mean that you’ve got the political or organizational savvy to figure out how to bring it to be inside of a large, complex organization. The best idea guy in the company might not have the greatest executive polish, might not be able to sell it to the investment committee, etc. So again, great ideas might perish because the person putting them forward doesn’t have the right profile to make them happen.

3. The problem of politics. Strategies and approaches don’t just happen. The happen in the context of a political process. This is true in both communities and in companies. The status quo is probably associated with a particular set of leaders whose credibility went into getting them pushed through. Doing something different means that leader is exposed to incredible pressure for “backtracking” or “admitting failure”. This often means that new ideas are judged not so much on their merits as by who is pushing them. People in different political camps might oppose it just for that reason as much as any other.

It takes a unique leader to change an organization from the inside. That’s why you so often see that it takes an outsider coming in to create real change. That outsider isn’t personally invested in the policies of the past. To me one of the most compelling business stories remains Andy Grove’s recounting of he and Gordon Moore sitting in the office as their memory chip business was getting crushed and asking themselves, “If the Board fired us, what would the new guy do after he walked in that door?” The answer was clearly to get out of the memory chip business. So they asked themselves, “Why can’t we get up, walk out of this room, walk back in that door and do the same thing?” And that’s what they did. Their willingness to abandon a business that they viewed as core to Intel’s very being led to that company becoming one of the long run, sustainable tech business successes as opposed to yet another piece of road kill.

4. The tyranny of the organization chart. Whether or not an idea finds acceptance is as often as not driven by the perceptions of the credibility of the person making it. This means ideas that originate in lower levels of organizations seldom get a hearing because of the organizational status of the person who has it.

I like to get out and meet people, and I continue to be amazed at the people I come across from various organizations that are among the smartest and most innovative thinkers I’ve met. But few of them are taken seriously by their own organizations. To avoid exposing the guilty, I won’t give examples, but will say I know multiple folks who have managed to build significant external credibility in the world at large but have little to no credibility at their own companies.

Again, this is a simple matter of organizational dynamics. What you say in an organization is viewed through the lens of the box you occupy on the org chart. For people at junior levels of the organization, that means that they will likely never have opportunities to present new ideas, probably will be too afraid to fully voice them if they do, and will likely have them rejected in any case. It’s tough to imagine the CEO of a company taking advice on how to run the place from a middle manager. It just doesn’t happen. And that’s regardless of how good that middle manager’s ideas might be. As with many things, myths show us the unpleasant truths about the world. Few people ever believe their Cassandras.

That’s a huge reason companies so often turn to outside advice. An outsider is not burdened by having the millstone of the organization chart around his or her neck. That person’s credibility is judged differently, and the person asking for the advice is much more likely to be receptive. When the outsider sits across the desk from the CEO, it’s very different from a junior manager sitting across the same desk, no matter whether the ideas be exactly the same.

This might be the most interesting of all problems. Most large organizations have enormous talent at all levels. The question is, how do you harness that talent for the benefit of the organization without obliterating an organizational hierarchy that servers real and legitimate functions? This is a question worth serious study.

I think this goes to show the problems facing the innovator, business, city, or region. In short, nearly all of the problems of innovation are problems of organizational dynamics. Innovation is man’s natural state. But culture and organization conspire to suppress it.

Despite my rhetoric about the Midwest being out of ideas, that’s not strictly true. I’m absolutely convinced that the Midwest has the talent and the ideas necessary to innovate and to be successful in the 21st century world. The problem is that they imprisoned inside a culture and civic organizational structure that renders them impotent. It’s like I said before of Silicon Valley, the real secret to Silicon Valley isn’t having great universities, tons of venture capital, or organizations that push a high tech strategy. It is the social structures that enable rapid innovation. Without those social structures, the Midwest can raise VC funds and support university technology transfer programs till the cows come home, but it is not going to have the hoped for results.

This is the challenge facing the Midwest and its companies. Every place has a culture, but it is almost always an organic thing that grew over time without any deliberate attempt to shape it. Every place has organizational structure, but organizational theory is not high on most political or business leaders’ list. But that is what we need to do to move the ball forward and adapt to a rapidly changing world. Because if the Midwest ever figures out how to out innovate and move faster than the rest of the world, then it will find a way to prosper no matter which way the 21st century takes us. If not….

I won’t pretend these are easy problems to solve, but this is where we need to look if we want to re-energize our economy and our businesses through innovation.

More in This Series

The Setup: Chicago – a Declaration of Independence

Part 1A – Metropolitan Linkages

Part 1B – High Speed Rail

Part 2A – Onshore Outsourcing

I agree that innovation is one of the keys to an exciting future for the Midwest. And in that respect — and others — I’d like to discuss the impact of Boomers.

Full disclosure: I turned 60 last month, and having a certain personal interest in the subject, I’ve been doing some reading on where the Boomers are heading. What I’ve found has gotten my juices flowing, both in terms of my own personal future, but much more in terms of how me and 76 million other Boomers are going to change things in the next couple decades.

This has HUGE implications for our cities and the Midwest, and the midwestern cities that grasp these implications and act on them are going to have some pretty exciting days ahead.

This is not a billboard for Boomers. I raise the issue of Boomers specifically in the context of creativity, innovation and the future of the Midwest.

Ten years ago, it was predicted that Boomers would be bankrupting social security and Medicare, and there would be a huge hole in our workforce. It was assumed that Boomers would continue to migrate south into age-segregated communities, and indulge in leisure, golf-cart-type pursuits. This was based on extrapolating then-existing trends. Those trends and assumptions have been built into demographic and hundreds of other unspoken projections about how northern and southern cities would look in another ten-twenty years.

But these trends have already proved to be obsolete. “Bleeding Edge” Boomers and those right behind them are taking a very different direction from their parents. And it’s going to take awhile for everyone to take this into account. (This is built into the Baby Boom. Society has consistently been unprepared for Boomers.)

With apologies to all who are bored stiff with Boomers, consider the following: 8,000-10,000 people are turning 60 every day. By 2020, one out of four Americans will be over 65. The vast majority of Boomers have no intention of retiring — ever; and even if they wanted to retire, most Boomers can’t, since their now-depleted retirement funds were never designed to cover their increased longevity. The fastest growing segment of the workforce — by far — is the over-50 segment, and it will constitute an even bigger slice of the pie in the decade ahead.

We are now looking at the prospect of a relatively healthy, productive, experienced, educated workforce of 76-plus million Americans who control more than half the nation’s wealth and who will end up counting for a huge percentage of the workforce. Boomers will be at a new point in their life cycles, with as much as 25 productive years ahead of them, without the responsibilities of raising a family.

Implications for innovation and creativity? Not only are Boomers going to stay in the workforce, they will be an enormous catalyst for and source of innovation. Boomers (at least in their own minds) feel like they’re just getting started. The majority of Boomers view “old” as 89 — which is currently older than the most optimistic of average life expectancies of Boomers [!] They feel ready for new challenges, want to stay involved and relevant and are hardly invested in the old ways of doing things. Arguably, the Boomers have lived through and embraced far more technological change than younger people have. This is an age group that started with three black-and-white TV networks, no cell phones and no computers, and they’ve spent they’re entire life adapting. You might buy a Jitterbug phone for your grand parents, but you’d better figure on a Boomer buying his own Iphone. Further, most Boomers welcome the chance to work with younger professionals (there’s certainly not the generation gap between Boomers and their kids that existed between Boomers and their own parents). The presence of Boomers and younger people on the same entrepreneurial team is apt to be a positive when it comes to innovation, whether the innovation comes from Boomers or younger people. At the very least, Boomers can provide mentoring, business experience, contacts, etc.

When you think Boomers, think Creative Class. Whatever effect the Creative Class might have on urban areas, magnify it by about as many powers as you want, because Boomers will swell the ranks of the creative class by millions as they move into the new pursuits that, if the polls are correct, should be more focused on personal passions than earning a secure buck.

Now go back to something in the Urbanophile’s article — that some portion of innovation is going to come from smaller, entrepreneurial outfits of four-ten people. These may, in fact, not even be particularly stable, but rather ad hoc teams that come together to tackle specific projects. This is right up the alley of Boomers in the next two decades. Boomers, when polled, say that what they do next will be less structured and more flexible than what they’ve been doing all their lives. They want to pursue multiple opportunities. They intend to devote some time to the not-for-profit sector, some time earning money; some time relaxing, but whatever they do, they intend for it to be more on their terms — working less than a 50-60-hour week; flexible arrangements; being their own bosses; working with people they enjoy; trying out new things.

The Brain Drain has been discussed at length in this Blog. But it’s generally been in the context of younger people. Consider the impending brain drain of Boomers from Midwestern cities. Midwestern cities need to figure out how to retain their Boomers and attract new ones. On that score, see below.

Implications for Midwestern Cities? Most Boomers want to live in age-integrated communities and have generally rejected the “golden years” Sun-City type fates of their parents. So, where will they end up? Well, many want to stay right where they are – if they can afford it. Let’s not forget that, in the past, many retirees moved to the Sunbelt not for the weather, but because it was affordable on a retirement income. In doing so, they left behind, in many cases, life-long friends and social networks. They often became isolated from their families and grand-kids in the process. Boomers are going to be a lot less likely to make these sacrifices, if recent polls are accurate. They want to stay involved and active in communities they’ve helped build. They want to stay integrated in urban settings with people of all ages. But cost-of-living will be a factor. Sure, many Boomers have, and will continue to, move back to the urban cores. But, in the case of Chicago, that’s not going to be an option for many of them. And when it comes to Boomers, “many” means “many.”

Now think back to the recent articles in this Blog discussing a hierarchy of labor that would permit people to achieve a higher standard of living at a lower cost in places like Indy or Columbus, while still being able to access the culture and nightlife of Chicago through light rail. This arrangement should, it seems to me, be as attractive to many Boomers as it would be to younger workers with children. Maybe even moreseo, because, in addition to access to culture, Chicago ex-pat Boomers would have access to their Chicago-based, friends, families, churches, etc.

A city like Milwaukee, for example, that could offer a “micropolitan” weekday experience for Boomers at a reasonable cost-of-living that is a short train ride from Chicago could offer a much better alternative to a Chicagoan Boomer than moving to Phoenix. Imagine a city like Milwaukee or Indy specifically marketing itself to Boomers. Imagine Boomer-friendly college campuses; programs that create opportunities for Boomers and younger entrepreneurs to link up; live-work developments; real estate subleasing markets that accommodate seasonal Boomer housing. Imagine more in-city “intentional communities” (example: Lincoln Park Village in Chicago) that can take the edge off of winter-living for some aging Boomers by providing services that are now generally only available in assisted living environments …

Forgive the length of this comment. But the implications of what the Boomers do next amount to a heretofore — in the history of the world — unknown demographic phenomenon. It’s staggering. The advent of the post-60 Boomer is as much of a game-changer as anything discussed to date in this Blog. I’ve just scratched the surface of this topic, and I strongly encourage the Urbanophile to devote another article to this phenomenon.

Cheers,

Ironwood