Universities and health care, “eds and meds”, have been in a huge growth cycle over the last few decades. Many communities have been pinning their hopes on anchor institutions like a university or research hospital to retool their economies for the 21st century.

Yet the higher education industry is facing a convergence of several trends and forces that are threaten their future. At a minimum, schools need to be figuring out how to navigate these choppy waters ahead.

Here are six forces converging on colleges today and in the near future:

1. The number of college students will soon plunge. Professor Nathan Grawe, in his book Demographics and the Demand for Higher Education, built a model that projects the future demand for college. He found that starting in 2025, the number of college bound students is likely to decline substantially.

Figure 6.1 from Grawe’s book

The elite top 50 will continue to experience robust demand, but others won’t be so luck. As Grawe told the Chronicle of Higher Education:

The bottom line is there’s almost nothing that’s going to get us around the fact that, in the late 2020s, we should see really significant reductions in enrollment. If your strategy for this is to try to increase enrollments, the model suggests that that’s a bad idea.

Grawe has provided a large amount of grim data on his web site.

2. Tuition is soaring at rates far higher than inflation. This chart from Carpe Diem and AEI says it all. Tuition and textbooks have nearly tripled in price since 1997:

How much more can students and their parents take?

3. Student loan debt is soaring. Earlier this year New York magazine put together this astonishing chart of the growth of student loan debt relative to other kinds of loans:

![]()

CNBC reports that:

Over the last decade, college-loan balances in the United States have jumped more than $833 billion to reach an all-time high of $1.4 trillion, according to a recent report by Experian.

The average outstanding balance is now $34,144, up 62 percent over the last 10 years. In addition, the percentage of borrowers who owe $50,000 or more has tripled over the same time period, according to a separate report by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau.

The $1.4 trillion in student loans outstanding new exceeds total credit card debt and total auto loan debt. Some people now have over $1 million in student loan debt.

4. The over-education problem. One factor that’s seldom directly pointed out is the disconnect between the number of people who go to college, and the number who can plausibly cash in from a degree.

34.9% of people ages 25-34 have a bachelors degree or higher. This is probably a fair proxy for the share of younger people who will likely get degrees. But is 35% of the American public able to get a high paying job? Indicators are not.

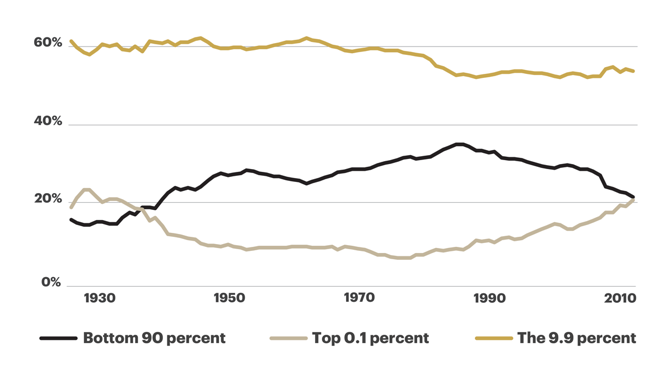

Much as been made of income inequality, the decline of the middle class, etc. Some share of the population, probably 20% or less, is reaping disproportionate rewards in the modern economy. Others have seen stagnating real wages. For example, the Atlantic just ran a cover story talking about the “9.9%” that had this chart showing the share of wealth held by the 0.1%, the 9.9%, and the bottom 90%:

Even if people in the next decile below the 9.9% are doing well, that still leaves a ton of people with degrees who don’t necessarily face great economic prospects.

They might instead end up changing diapers at a DC day care center. Washington put forth a mandate that day care workers have a college degree, which indicates they must believe there will be no shortage of takers.

Combine a degree that won’t grant access to the high wage economy with student loan debt and it’s a recipe for big problems for young people.

This is an area that deserves more study.

5. University inequality. It’s not just workers who face inequality, but schools themselves. The Wall Street Journal has been reporting on a potential shakeout among colleges, in which the higher end universities continue to do well, but those ranked nearer to the bottom are in trouble. In one article related to this divergence they note:

For generations, a swelling population of college-age students, rising enrollment rates and generous student loans helped all schools, even mediocre ones, to flourish. Those days are ending. According to an analysis of 20 years of freshman-enrollment data at 1,040 of the 1,052 schools listed in The Wall Street Journal/Times Higher Education ranking, U.S. not-for-profit colleges and universities are segregating into winners and losers—with winners growing and expanding and losers seeing the first signs of a death spiral.

Similar they written that many non-selective small liberal arts may be in trouble.

6. MOOCs. The rise of online education, notably in the form of “massively open online courses” has yet to disrupt the higher education model, but with the factors above bearing down, there’s a huge financial incentive to make this work. Industry after industry have been radically restructured by technology innovation, and it’s reasonable to believe that the business model of higher education will one day end up on the receiving end.

7. The credentialing cartel. It’s widely understood that the primary value in a degree is having it. The degree itself is perceived as a key credential granting access to the job market. As Austen Allred put it, “Would you rather have a Princeton diploma without the Princeton education, or a Princeton education without a Princeton diploma?”

Universities are in effect a cartel who can levy an entrance toll to the professional job market. This may last for quite some time, or even strengthen, but there is again great value to be unlocked in breaking this cartel. The tech industry is a good example, where even famous companies have been founded by drop outs. If you are a great developer, it doesn’t matter what your credentials are. This has been one secret to that industry’s success.

None of these inevitably spells doom for colleges, and certainly not for any individual one. There is also a lot of nuance not captured in this short posting. But as a highlight of potentially disruptive forces, it shows that there is quite a collection of powerful disruptors and potential disrupters arrayed against the university environment. Savvy institutions should be working hard to get fit for the road ahead.

I haven’t asked my students to buy a history text in years. I give them all readings for free on blackboard. Am I unusual as a college instructor in that way?

The first two paragraphs of point 7 seem to contradict each other. The first paragraph seems to claim that the credentialing factor of an elite degree is the real value and the education itself is secondary. But the second paragraph seems to indicate that in the tech industry at least (and perhaps soon others?) it’s actually the quality of one’s education that matters and not the certificate one has.

In either case, it’s not clear how a change in this would affect the market for higher education. It seems like it could further entrench the status of universities that do a good job at educating people, or could promote some currently less-known ones that become known for such.

Universities have survived for many centuries. They’ll change, but they aren’t going to disappear. They are too valuable to too many interests.

The college dropouts who started businesses all dropped out of college 15+ years ago. Using Steve Jobs and Bill Gates as examples isn’t a great way to indicate how the tech industry is now.

The reason that big tech companies have the edge these days isn’t because of college dropout geniuses, it is because they can pay big bucks to big name PhD’s from Stanford and Berekely to develop the real cutting edge map. You may notice there just aren’t a lot of startups able to compete with Google and Apple and Microsoft these days, and it is because college dropouts don’t have the math and statistics chops to cut it.

Figure 6.1 from Grawe’s book certainly looks alarming, but the time frame needs to be at least two generations, and the scale needs to start at zero, in order to draw valid conclusions. Frankly, it appears to be a normal demographic wave.

After Baby Boomers passed through the K-12 system, local school districts realigned and closed schools while the Xers were passing through. Then there was another suburban school-building boom as the Millennials came to school age in the mid-late 80s. Now that the last of them are graduating from high school, whatever is happening to K-12 today is coming to higher ed next.

The first two paragraphs of point 7 seem to contradict each other. The first paragraph seems to claim that the credentialing factor of an elite degree is the real value and the education itself is secondary. But the second paragraph seems to indicate that in the tech industry at least (and perhaps soon others?) it’s actually the quality of one’s education that matters and not the certificate one has.

In either case, it’s not clear how a change in this would affect the market for higher education. It seems like it could further entrench the status of universities that do a good job at educating people, or could promote some currently less-known ones that become known for such.

@keaswaran – It really depends on the industry. Being successful as a programmer is sort of like being successful as a basketball player. That is, “Ball don’t lie”: a great programmer is simply a great programmer no matter where he/she went to school just as a great basketball player is a great basketball player whether he/she went to Duke or Central Arkansas (a la Scottie Pippen). Tech companies hire for the skills as opposed to the credential in and of itself. Computer science majors from Stanford get great jobs because they’re great at computer science (and not just because they went to Stanford).

Not all industries are like this, though. Finance and law definitely come to mind where your alma mater matters significantly and it’s actually getting even *more* elitist. I went to a “meh” law school but made law review and got top grades, so that was sufficient to get entry into a BIGLAW job 15 years ago. That’s definitely NOT the case any longer – the large law firms aren’t even bothering to interview at anywhere other than the top law schools even for token representation. Elite investment banks and management consulting firms are like this, as well – they absolutely want the Princeton *degree* (not the Princeton education).

There’s a reason why affluent professionals are more obsessed about *where* their own kids go to college more than ever. The thought of not going to college at all isn’t even a consideration for that group as a general matter.

Tech is the one exception to the credentialing cartel. But I believe even tech is becoming more credential driven these days, as the industry corporatizes.

Something that can’t go on forever won’t. The bloodletting will be de minimus at the most elite schools, cushioned as they are by multi-billion dollar endowments. As your article makes clear, it is likely that both volume (# of students) and price (tuition, room & board) will be trending negative and that will impact revenues materially. Few schools will escape this looming catastrophe.

Colleges will not be able to shift teaching loads from expensive, tenured professors to less costly part timers, short contract instructors, more adjuncts, etc. Such “contingent faculty” already accounts for two-thirds of the teaching load at flagship public universities, over 80% at community colleges. In the late 1980’s, contingent faculty accounted for less than 30% of the teaching load at accredited 4-year universities. That cost saving tool has already been wielded to the fullest possible extent. Certain disciplines, including foreign languages and other elements of the traditional liberal arts curriculum, will be abandoned. This trend has already started. Some law schools have begun to shrink into oblivion.

I expect the largest effort at cost reduction to be aimed at the overfed administrative employee category. In the last 25 years, non-teaching administrative staff has more than doubled, a rate of growth that’s 2x that of overall enrollment. Many of these positions are quite well compensated, e.g., Deans of Diversity, we’re not talking about clerical type positions. I wouldn’t be surprised if the trend to compensate university presidents like CEO’s also reverses.

Smart university administrators — Purdue comes to mind — realize what the future holds and are preparing their institutions to survive the coming storm.

The other things have been considered threats for years, but haven’t really upset the college model. No. 1, though, has the ability to do more damage than points Nos. 2-7 combined. With the declining birth rate, logic would seem to dictate we throw open the doors to just about anyone who wants to come in and legalize who is already here just to keep our numbers up. Really, point No. 1 is going to disrupt not just colleges, but a whole American economic model built on continuous growth.

“Demographics is destiny”. If you don’t believe it, ask Japan (and soon enough, China).

I didn’t make this point as well as I should have above. (The graph looks alarming but I’d like to be able to put it in a multi-generational perspective instead of just less than two decades.)

Maybe I’m wrong about this, but my impression (never having been to the country and not really knowing anyone from there) is that Japan is a nice to live. Nicer than the US.

The issue is that the country is virtually closed to immigration, has a very low birth rate, and life expectancy is quite high.

So it is a rapidly aging society, one that will soon lack the working-age population and productivity (and tax base) to carry the overwhelming social security cost.

Huh? http://www.pewhispanic.org/2015/09/28/modern-immigration-wave-brings-59-million-to-u-s-driving-population-growth-and-change-through-2065/

My comment was about Japan, in response to P Burgos.

I thought that the economy was bifurcating such that the proportion of jobs paying low and high wages was increasing, such that it is plausible that 35-40% of workers in the US would be able to get high paying jobs (though not all would require a college degree). If anything I would think that continued automation would continue this trend, meaning that the value proposition of college will remain mostly unchanged in the near future.

@P Burgos – What we’re seeing is that colleges themselves are bifurcating in terms of demand.

The overall demographic trend of lower college enrollment has already started. We’ve seen many colleges face enrollment issues because of declining high school graduate numbers with primarily lower tier public (e.g. the “directional” schools) and private colleges bearing the brunt of it.

What’s interesting, though, is that despite the fact that there are fewer high school grads today than 10 years ago, the demand for spots at top colleges has actually *increased* dramatically. The Ivy League schools and others in their tier (e.g. Stanford, MIT, University of Chicago, etc.) are receiving a record number of applications and they keep breaking those records every single year. This has a pushdown effect where what the elite considered to be “backup schools” a generation ago (e.g. the flagship public schools of the Big Ten, next-level private schools like USC, Tufts and Boston College, etc.) are now drawing elite level students en masse because competition for spots for the Ivy/Ivy-equivalent schools is so fierce. What used to be a linear spectrum of school quality now looks like a dumbell curve of a critical mass of top level schools that are drawing record applications and enrollment even with a shrinking college population overall… and then an even larger mass of lower level schools on the other end that are getting hammered by declining enrollments. There are very few schools in between now (which is sort of a reflection of a lot of aspects of our society).

So, I think it’s important that the decline of the overall college-aged population isn’t going to impact all schools evenly at all. If anything, it’s creating a larger “flight to quality” where demand for spots at top schools and programs (e.g. computer science programs at many schools that the general public probably thinks of as pedestrian) is increasing dramatically.

This is also one of Gawes findings. Demand for elite (1-50) schools is projected to increase. Demand for what he labels national schools (51-100) is projected to decline based on raw demographics, but he speculates that push down from excess elite demand will make these schools turn out alright too.

With a flight to quality (and fewer grads overall) might the financial returns to college rise for grads in the coming decades? The basic idea that with fewer grads and a higher proportion coming from the super elite (Ivies, MIT, Stanford, etc.) and the elite schools (Tufts, USC, etc.) employers will be more willing hire grads and will have fewer to choose from. That is to say, HR and companies will be more willing to hire recent grads with the name degree for CYA reasons.

Possibly a little of the opposite: as the #21-50 national universities get the “leftovers” from the Ivy League +12 (MIT, Duke, Stanford, Chicago, Rice, Washington U, Vanderbilt, Notre Dame, Northwestern, Johns Hopkins, Caltech), there might actually be a drag on the financial returns to attending those top 20 schools. Especially in specific program areas where an otherwise second rank school is top rank.

I was more thinking of the overall return for all students, not just those at the top 10 or 20.

That’s going to depend entirely on how much more of the professional world is automated/taken over by AI, not on the educational attainment of people.

Fair point about AI/machine learning. I am pretty skeptical that AI/machine learning is going to have all that much of an impact in the next couple of decades, although I hope I am wrong about that, because a vast increase in material wealth would I think do wonders for the world. Still, automating processes is harder than it often looks at first, even with very powerful machines and algorithms. And even if AI/machine learning ends up working pretty well, for legal and hierarchical CYA reasons I suspect that you will still need people to exercise judgment as to whether to follow the recommendations of the computer. If something goes wrong saying that “the computer told me to do it” seems unlikely to be a very good legal defense, nor does it seem like a good explanation to keep you (and your boss as well) from getting fired.