Tocqueville’s Democracy in America has a chapter entitled “Why Among the Americans All Honest Occupations Are Considered Honorable.” In it he noted that because America lacked an aristocratic tradition of leisure, labor had not been stigmatized as something inherently degrading to man:

In America no one is degraded because he works, for everyone about him works also; nor is anyone humiliated by the notion of receiving pay, for the President of the United States also works for pay. He is paid for commanding, other men for obeying orders. In the United States professions are more or less laborious, more or less profitable; but they are never either high or low: every honest calling is honorable.

Not only was work not inherently degrading, anything one did, whether it be serving as president or pushing a broom, was equally as valid as anything anyone else did. They may have been economically distinct, but they were ontologically identical. If you put in the proverbial honest day’s work for an honest day’s pay, if you provided for yourself and your family, then you and your work were worthy of the honor and respect of your fellows. What’s more, in America to not work was what indicated personal degradation of spirit. Per Tocqueville:

The notion of labor is therefore presented to the mind, on every side, as the necessary, natural, and honest condition of human existence. Not only is labor not dishonorable among such a people, but it is held in honor; the prejudice is not against it, but in its favor. In the United States a wealthy man thinks that he owes it to public opinion to devote his leisure to some kind of industrial or commercial pursuit or to public business. He would think himself in bad repute if he employed his life solely in living. It is for the purpose of escaping this obligation to work that so many rich Americans come to Europe, where they find some scattered remains of aristocratic society, among whom idleness is still held in honor.

This idea of the honorableness of work held sway in America for a long time, but that time is past. In America today, the very concept of work qua work is increasingly held in contempt, as in the aristocratic age.

This surely began before I was born, perhaps in the 60s era of “turn on, tune in, drop out.” Yet I have personally witnessed a major sea change in the perception of labor in my own lifetime over the course of several signal events.

The Volcker Recession

America has long been the industrial powerhouse of the world, reaching its apogee in the 50s and 60s. By the 70s era of gas lines and stagflation, it was clear something was wrong, though not exactly what. Yet on the whole America conducted business as usual. Arrogant management continued to be more or less indifferent to product quality and inefficiency. Labor continued to engage in frequent strikes as if there were still massive gains to appropriate.

In the late 70s things started to change. Jimmy Carter began a major deregulation of key industries. Reagan came into office in the 1980s promising supply side tax cuts. He was also hostile to unions. Early in his administration, he fired every air traffic controller who had gone out on an illegal strike.

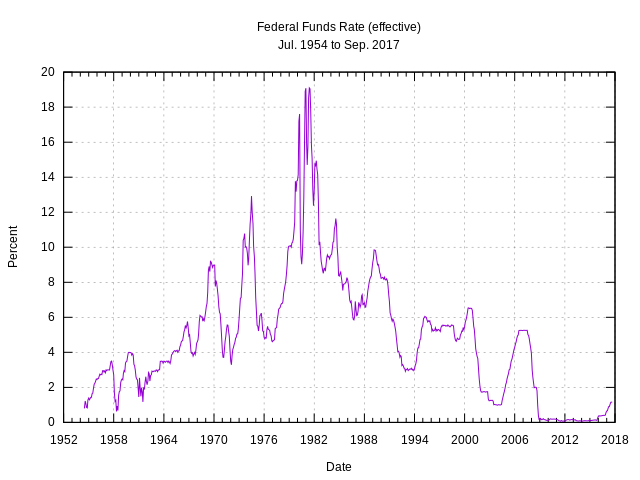

But it was Fed chairman Paul Volcker who had the most profound impact, jacking the prime rate (the most widely reported figure of the time) north of 20% in order to break the back of inflation, sending the country into a steep recession. Here’s a chart of the fed funds rate that gives a picture of the extremity of these rate hikes:

The Idea of the McJob

When I was a high school student my first real job was bagging groceries at Winn-Dixie. This wasn’t an unusual experience. I remember as a kid that many adults would tell me with no apparent embarrassment that their first job had been at McDonald’s. Holding a job like this was just part of the cycle of life, much like going into the service used to be.

Two events changed this in the 1980s. The first was the recession, which shattered the illusion of American industrial dominance forever. The whole idea of a good job for life on the assembly line was now seen to be dangerously naive. This is the era when “you absolutely must go to college to succeed in life” meme took hold. It was already clear that the long term trajectory of manufacturing and a middle class job with a high school diploma (or less) was heading to the scrap heap.

The second was the closing of the bootstrap frontier. By this I mean the severe curtailing of the ability of people to work their way up from the bottom in business. How many old school Wall Street types started in the proverbial mail room? A lot of them. My father’s wife started work at age 17 as a teller at a small savings and loan in Louisville. Twenty five years later she was running all of mortgage lending for Fifth Third Bank’s Kentucky operations – all without a college degree. Even today you hear CEOs – usually in their 50s or older – talk about how they started with their company by driving a truck or something.

Those days are largely gone now. While in some industries like retail you can still work your way up, it’s less common, and you’re almost certainly not going to make it without getting a college degree along the way. Nobody on Wall Street is starting in the mail room today. Techies who drop out of school to start companies are starting in effect at the C-level of their organization, or in an otherwise high status position, not a traditional entry level job.

With formerly entry level jobs increasingly ones with no to a limited career path and low pay and benefits, and the only way to career success seen as being through college, a new concept of work started to emerge. In 1986 it was given a name, the “McJob.”

The phrase “McJob” was designed to label a real and important effect, and presciently so as we see today. Namely the bifurcation of the economy. Nevertheless, it went beyond a critique of economic conditions to something more fundamental; it said these were jobs not worth doing and unworthy of human dignity to hold. It eroded the idea of work itself as honorable.

Today I’m amazed how many teenagers and college students don’t work at all, especially not at old school grocery bagging or burger flipping jobs. It seems that you’re better off getting in more extra-curricular activities or doing volunteer work to burnish your resume than actually working, which says something profound.

Strauss and Howe’s Generations

In 1992 Neil Howe and William Strauss published the book Generations. This book took a Vico-like cyclical view of history in which four generational archetypes repeated over time in an endless cycle. This cycle was presented as de facto deterministic unless some severe outside shock interrupted it.

Howe and Strauss coined the term “Millennial Generation” to identify a current instantiation of one of their archetypes. In their cyclical theory, the Millennials were a reincarnation of the Greatest Generation that lived through the Depression and won World War II, leaving modern American prosperity in their wake. The Millennials, they said, would achieve similarly great things. Because of their cyclical theory, this result was presented as an almost historic inevitability, even though the Millenials were still small children.

This concept captured the public imagination in way that led to a change in the way that generation, much of it as yet unborn, was to be raised. Howe and Strauss had already observationally described the “helicopter parenting” of Millennials vs. the latch key kids of Generation X (they would say think “Baby on Board” signs vs. “Rosemary’s Baby” or “Damien Omen II” in which children were literally Antichrists or demonic). This was already underway.

What changed is that Millennials began to be told from nearly birth that they were destined to be nothing less than the salvation of America, that they are more moral, more community spirited than any previous generation, and like the Greatest Generation they would slay the dragons threatening our country, leading us forward into a better brighter future. When Barack Obama said, “We are the ones we’ve been waiting for,” he was flattering a particularly Millennial conceit. It’s no surprised they loved him.

The effects this produced in the Millennials have been much written about. But one key one was the sacralization of their own personal desires. After all, if you’re really destined to change the world for the better, society needs to adapt to you, not you to society.

That’s why workplaces in America have bent over backwards to accommodate Millennial preferences. We also see a generation that wants not just to have a job, but a job with meaning. People who would rather do something that creates some sort of public good (like teach in an inner city school) or pursue a particular personal passion than to engage in the soulless search for money.

There’s much that’s good and noble in this. On the other hand, it has redefined work into just another lifestyle accoutrement. Work is no longer primal, central. Rather, it is part of the portfolio of your life. The role of work has become, ultimately, self-actualization and the satisfaction of Millennials’ sacralized personal desires. In that regard, the line between work and play and life have blurred. In part that’s because the notion of work as something you just have to do, something that is part and parcel of being a fully formed adult, no longer exists. Work properly so called must be an extension of your being. Yes, if forced financially, Millennials will work any job they need to. And they are more than willing to engage in productive labor. But their idea of a job is to somehow promote personal growth or self-actualization. You can do work that doesn’t, but it’s second rate – a McJob. Again, this shows the bifurcation not just of income, but in views of work. Some work is worth doing, other work is not.

Though I’m not a Millennial, I should be sure to include myself as well, since I’m writing this blog instead of running multi-million dollar technology projects like I used to. So guilty as charged.

The Dot Com Boom

The last hurrah of the Volcker boom was the dotcom bubble. This was a Gen X and Boomer phenomenon, but it paved the way for the Millennial expectation of work as a fun and fulfilling place, not just a workplace.

Prior to the dotcom boom, I wore a suit to work every day and sat through terrible traffic driving to a client in the suburbs. I can assure you that I would have much rather have been downtown in casual clothes. This desire to be in the center of town didn’t originate with Millennials. But that was simply the way the world worked. We obviously wanted fulfilling and high paying jobs, but we realized that work was after all work. That’s why they paid us – to do things we didn’t want to do, like sit in traffic for hours every week. What’s that they used to say? – that’s why we call it work.

The dotcom bubble changed that. The desperation for talent was so high that anyone who could spell .com could get a job as a programmer. The Silicon Valley tech culture and catering to employees became the norm. It was insane in some ways. My employer used to have a beer cart come by on some afternoons, and that wasn’t unusual. While some of it got dialed back after the collapse, this permanently changed the culture of work.

Perry’s Deli in downtown Chicago used to put up “celebrity boards” of photos Perry took of his customers. In the 1997 board, about 75% of the people were in suits. By the 2000 celebrity board, it was more like 75% casual. It flipped almost overnight like dominoes falling.

This established the idea that employers must cater to the whims of fickle employees or they will cross the street to somewhere better. This concept has persisted as an ideal (e.g, in the “creative class”) even though the bargaining power of labor has collapsed since then. It’s no longer seen that workers should have to endure unpleasantness as part of their jobs or conform to employer expectations around dress, location, or hours. They may do it, but again such compromises are seen as defects, and generally in the employer. An enlightened employer, we think, should instead cater to the desires of employees.

Proletarianization of the Middle Class

The truth is, the economy never really recovered from the dotcom crash. The 2000s recovery was anemic, and we are de facto still in the Great Recession. The macro trend of bifurcation has so proceeded that the income and wealth gaps are now major public issues. This has in effect created two labor markets. One is the narrow high end market which still lives in like it’s the dotcom bubble. The other is everybody else, increasingly squeezed and increasingly low wage, a phenomenon Joel Kotkin has labeled the proletarianization of the middle class.

Those at the bottom are increasingly seen as exploited, and in a sense they are, though mostly by the system rather than by individual employers who are only responding to the new marketplace realities, albeit one in part created by those selfsame firms. But what’s more, in effect any job that doesn’t exhibit the self-actualization ethic of the top tier positions is now viewed as a McJob, regardless of pay. The values of the dotcom bubble and the Millennials have become normative. Work that does not live up to those ideals is seen as unworthy and impugning rather than affirming the dignity of the worker. In short, work itself as traditionally understood is now held in a form of contempt.

We see this in various ways. For example, many of those who advocate for more low skill immigration say that immigrants perform “jobs Americans won’t do.” But Americans did those jobs not long ago. What’s changed about those jobs? The jobs actually haven’t changed, just our attitude towards them. What’s more, if that new attitude is valid, is it moral to expect brown skinned foreigners to do work we think is beneath our dignity? I am a big champion of immigration, but not based on this type of logic.

Or consider the reactions of some on the left to the Congressional Budget Office finding that Obamacare will cause the equivalent of two and a half million people to voluntarily stop working. Europhiles have long bemoaned that America’s don’t take the whole month of August off, but the suggestion of the New York Times that this is “a liberating result of the law” seems a bit extreme. It may well be that there are some with such an extreme hardship that this does make sense, but the whole idea that people need to be liberated from unpleasant choices or tradeoffs related to work implies that work itself is not of that much value. To them it’s better to support people indefinitely on benefits of one sort or another than for people to be forced to work at Wal-Mart or something. The New York Times ideal is an aristocratic one; the aim is not to have to work at all, at least not at anything that isn’t inherently attractive to do.

I think there is indeed a serious problem out there with the quality of jobs and the two tier economy. In fact, I myself recently wrote that some people realistically will need to be supported on benefits indefinitely, and that terminating benefits to force them into $9 an hour is building a plantation economy, something too many on the right have no problem with. So I’m in the mix here. But in attacking legitimate problems, I’m concerned that we’ve undermined a core philosophical underpinning of American success, namely the view of the dignity of work and the ontological equality of labor.

We absolutely must focus on upgrading the quality of jobs. But apart from proposals to increase the minimum wage, there’s been precious little in the way of ideas to boost the fortunes of the middle and working classes. And even there the problem in seeing the inherent value of the worker remains. I don’t see those who advocate a higher minimum wage ever saying a kind word about working for McDonald’s or Wal-Mart, no matter how much those firms pay.

I believe the decline in our view of work is a consequence of economic change more than a philosophical movement per se. Yet the problem is not inherently an economic one. Even if we reverted to the status quo ante in our economy, it’s unlikely we’d change in our basic attitudes.

In my view one of the keys to actually working to change the quality of jobs is to see the worker’s performance of them as again having inherent dignity and worth, that workers are dignified in their labor no matter what job they happen to hold. The people who go to work at Wal-Mart or a warehouse every day reliably, who do their best even at a less than exciting jobs, ought to be seen earning a type of honor. This comes not from the work being done, but the person performing it and the idea of work itself. The difficult choice to take a less than self-actualizing job and doing it well ought to be seen as a better path than benefits or drugs or other alternatives. Of course receiving assistance shouldn’t be stigmatized (I’ve had government benefits myself). Many of those on drugs had circumstances that made it difficult to escape, etc. But ought we not see avoiding that and finding work, even difficult or dull work, as the normative path people should aspire to, not something from which we need to be “liberated”? I think we should.

One organization that figured this out is the military. Why do they make soldiers and such show such exacting performance and attention to detail on ridiculous tasks like making a bed, polishing boots, or swabbing decks? Part of it is instilling discipline no doubt. But part of it is teaching that the nobility of the task comes from that of the warrior, not the nobility of the warrior from that of the task. That’s why generally speaking military roles are held in high esteem both by those performing them and by the public at large, even if our military is often deployed for dubious ends.

Heck, even the communists got it, in their elevating the nobility of the farmer and the laborer, in propaganda if not in practice. This is no doubt part of its great appeal, something we might learn from.

The dignity and honor of work itself needs to once again be held in esteem by Americans. We should rediscover our inner Tocqueville. We must again see all honest occupations as inherently honorable, even McJobs. Work must once again be seen as “the necessary, natural, and honest condition of human existence.” Perhaps then we will actually set about the difficult task of making the work worthy of the regard in which we hold the people in their doing of it, not just moan about it.

Post Script

This concept of the decline of work first struck me many years ago when I saw a TV commercial that I believe was urging people to go to college. I can’t find it on You Tube and the details are a bit fuzzy, but I believe it starred Larry Bird working as a clerk in a hardware store paint department, presumably a megastore like Home Depot. While mixing paint he would wad up paper and throw it perfectly in the trash can every time. The moral was that if you don’t develop your talents, you could end up mixing paint, and what a terrible fate that would be. But what’s inherently wrong with being a clerk in a hardware store? There was a day not long ago when nobody would have thought twice about it. It was then that I realized something had fundamentally changed in how we looked at work. Update: A commenter informs me that this was actually a commercial for Prodigy internet service from 1999.

Great post and interesting thoughts. I agree that the early ’80s “Volcker Recession” was a turning point in the history of American work, particularly in its impact to the Rust Belt. I was in high school at the time, and I think you’re right that the “must go to college to succeed” meme took hold, or at least solidified, then.

However, as I view our current bifurcated economy, I put more of the onus on management and the elite, rather than workers seeking self-actualization. Again, going back to the early ’80s, I see that recession as coinciding with the earliest recognition that there were indeed product quality concerns and inefficiency matters that needed to be rooted out. The result was people who had spent decades doing a mediocre job in a semi-skilled position were told they couldn’t cut it anymore, replaced by a robot or a more productive younger worker. Those workers, and those who did not buy into the “must go to college” meme right away, began to filter into the McJobs you mention.

I don’t ascribe to the view that people don’t value honest work anymore. Work doesn’t value honest people anymore.

A hundred years ago, America was coming out of a long period of economic stagnation kicked off by the Long Depression (1873-1879) that really continued into the early 20th century. The key feature of that era was the automation of agriculture that was casting out farm workers across the nation. The most readily available jobs were in manufacturing in our big cities, and it’s not far-fetched to say early manufacturing jobs held the same low-paying, nowhere jobs stigma that today’s low-wage service jobs do today. Manufacturing jobs were plagued by high turnover and highly variable product quality.

In 1914 Henry Ford decided to address these concerns by introducing the then-unheard-of promise of $5 a day for Ford workers. Doing so more than doubled the average pay of his workers, but it dramatically reduced turnover, dramatically improved product quality, and elevated the profile of the manufacturing worker. This was the start of the modern concept of the middle class.

There’s a lot not to like about Henry Ford, but he got this right. There is a lot of talk about raising the minimum wage nationally, but a better approach would be for the large corporations that employ thousands of low-wage service workers to emulate Henry Ford and offer significant wage increases. I think we’d witness similar results.

Henry Wallace touched on some of this as far back as 1934 in his book, Statesmanship and Religion.

FWIW, the last paint guy I dealt with at a hardware store should be replaced with a robot.

Aaron, a truly thoughtful, insightful piece. I expect nothing less from you.

Like you, Aaron, and pete-rock, I trudged through work dutifully, in my case from the age of thirteen. But in my mind I knew I would go on to the professions, and it somehow made the work seem like a process to something better.

I’m struck now by my peers spending huge sums of money on their kids’ education, and the kids training to be teachers, social workers and nurses. Nothing wrong with that – but at such ridiculous prices!

When I went to college, I believe that in today’s money it was for half of what it costs today. And I’ve ended up, thankfully, with a rewarding professional job. I don’t think that is now a realistic trajectory.

I’ve heard complaints from the right about the “Europeanization” of America. When I lived in England for a year in college, I was struck by the lack of ambition I found among my college mates from there and the Continent. But I’m finding that to be the norm here now as well, although it has taken a generation or two to reach that stage.

Think about the car, and how we Boomers felt about it. It meant INDEPENDENCE. And SELF-SUFFICIENCY. It was worth sacrificing for. How many of our children feel that way?

We are all looking for fulfillment, in our jobs, in our homes. But like my European compadres of a generation ago, I believe we are increasingly finding that outside of the trajectory that has defined America for decades.

“Today I’m amazed how many teenagers and college students don’t work at all, especially not at old school grocery bagging or burger flipping jobs. It seems that you’re better off getting in more extra-curricular activities or doing volunteer work to burnish your resume than actually working, which says something profound.”

I interview a lot of college and law school grads and this (for better or for worse) seems to be where we’re going. Over the past years, it has been increasingly rare for me to see resumes with any type of “McJob” experience from college grads. Granted, we’re most impressed with internship experience in our industry, but we still used to expect at least some type of McJob work during your freshman or sophomore years of school when internships aren’t as readily available. Today, there definitely seems to be more of an emphasis on volunteer work and school activities.

To be sure, volunteer work is excellent and we love seeing it on resumes. Society as a whole needs to be more giving of their time and resources. Some of the volunteer activities that I’ve seen recent college grads perform are way beyond what was “standard” for my own college years. (More on that in a moment.) However, this is a disadvantage to those that come from lower income backgrounds where they need to work in McJobs to support their education costs (or even families) instead of being able to take advantage of a lot of volunteer opportunities that employers are increasingly more impressed with.

On a related note, the Millennials sometimes get a bad rap in the media. I’m a little bit older than the Millennial generation (just turned 36), so I’m kind of in that position of being at the tail end of Generation X while still interacting with a lot of Millennials. One thing about Millennials is that they are NOT lazy. Quite to the contrary, their experiences by the time that they graduate college (much of it due to the volunteer work that they engage in) collectively dwarf what was “normal” for when I graduated college. They’ve started and managed more organizations, traveled to many more places, and have had incredible internships. These kids are completely on the go 24/7.

However, Aaron’s post alludes to something that Millennials (as a general rule) have no patience for: grunt work. They have been exposed to an incredible amount of high level experiences by the time that they have graduated college, but never had to deal with the mundane day-to-day tasks that those of us who grew up working in some type of McJob during our high school or college years understood sometimes come with the territory even in the most exciting work environments on paper (i.e. an Internet startup, international public policy, etc.). “Working your way up” simply isn’t in their mindset – they’re already so used to being at the top at every place that they’ve ever worked or volunteered at that they’re not very good at dealing with incremental steps to their respective careers.

Now, this mindset is very good for entrepreneurship. Those years right after college when people are much more free to move (both geographically and career-wise) without having to take care of families are the prime time for starting up companies for aggressive, creative and restless people, and the Millennials are full of those types. So, I expect the Millennials to outpace previous generations on that front. The issue, of course, is that only a small tiny sliver of the population will ever be successful entrepreneurs, so the vast majority of Millennials are going to end up in jobs where they can’t just skyrocket their way to success. Since they never worked at a fast food restaurant or grocery store like previous generations of teenagers did, they have no basis to compare what a “mundane job” truly is, and so I can foresee a ton of job dissatisfaction coming down the pike far beyond even what our Prozac-fueled older generations have experienced (if it isn’t happening down already).

pete-rock and Frank the Tank touched on what I think is a big reason McJobs or grunt work don’t get “dignity or honor” anymore. It’s because those jobs don’t pay enough for anyone to be invested in them.

What pride can you have in your work if you slave away at two jobs (because neither will hire you on full-time to avoid benefits) and can barely keep your head above water? The coal miner, meat packer, or railroad worker of 100 years ago may have had a horribly unpleasant and dangerous job, coming home smelly and dirty, but he could still support his family and even afford a modest house. Can the Wal Mart cashier, burger flipper, or janitor of today do that? Not so much.

A crappy job for decent pay is one thing, but a crappy job for crappy pay is nothing anyone can really be proud of.

The street peddler, cobbler or farmer on the plains could barely keep his head above water- but that struggle was honored. Today one is seen as a sucker.

The biggest reason no one working for companies like Wal-Mart has any sense of pride because they’re never rewarded for your work. You can come in with your held high every day, do amazing work for a company, and never see a raise. Or, if you’re lucky, one 25 cent raise. After a year or two, it’s really hard to care, especially when it turns out your big reward is getting scheduled 35 hours a week instead of 20 (and believe me, they WILL hold that over your head).

The only way to get ahead at Wal-Mart of McDonald’s is through management, which means signing your life away for a salary. Because once those companies don’t have to pay you by the hour, they view your soul as there’s. For 6-7 days a week, they’ll own almost every waking moment of your life for a cool $30,000 (or less). In the end, as salary, you’ll barely be making more on a per hour basis 0 but hey, if you drive your workers into the ground to make some crazy metric, they might throw an extra $500 your way!

I’ve worked in office settings, and honestly, the work at Wal-Mart is just as demanding. While an office job requires more specialized skills, even the most frantic professional environment is generally leaps and bounds better than the daily grind in the service industry. You literally get worked like a slave – just because you don’t have to fill out Excel spreadsheets, that doesn’t mean it’s not hard.

Granted, you probably have a negative opinion of Wal-Mart workers because you’ve had bad experiences with the slackers. But what you didn’t realize is that the slackers get maybe 10-15 hours a week and are fired and rehired all the time. They aren’t getting rewarded for their laziness, but driven into abject poverty.

For every slacker, there are several people working their asses off with no light at the end of the tunnel.

Somewhere, instinctively, all those kids at college no it. That’s why they’re studying 50 hours a week in the hopes that they’ll be admitted into the pearly gates of the upper middle class, where the brutal reality of most the rest of America is hidden. Even still, more of them wind up in Starbucks than you’d ever guess.

…and a crappy job for crappy pay for a person who has an undergraduate degree seems to be “the new normal”.

Forgive a personal excursion here.

My generation of my family is virtually all Midwestern-origin Boomers (siblings and their spouses and my cousins). I understand that we may be a bit unusual; my siblings and I grew up with two college educated parents in the 60s and 70s.

I attended a reunion of my siblings’ families over the weekend. All the 10 “kids” in the next generation are Millenials, aged 16-30. Four of the five oldest have graduated college, and among them, they have six degrees. Three more are in school now, with two more about to start.

Of the five past college age: One landed a job as a contract/temp. The oldest is still searching for a professional job while working at a part-time gig 18 months after graduation; she fights bias against her non-professional work experience and liberal arts degrees. One started his own low-tech business. Two looked for months after graduation (while living with parents) before snagging decent middle-income entry level jobs.

All of them, like their parents, worked “McJobs” during high school and college. Two served in the military reserves (one is a combat veteran). These are not slackers, nor entitled kids of helicopter parents who think they’ll start at the top.

The economy is just way different today than it was 30+ years ago…even for smart, hard working people with the values and attitudes Aaron has highlighted. I must admit to some worry about “the kids” and their kids if they do not become another “greatest generation.

“A crappy job for decent pay is one thing, but a crappy job for crappy pay is nothing anyone can really be proud of.”

If you don’t find dignity in your work where do you look?

What price do you put on your dignity?

I actually have quite a lot of family from the coal, steel, rail areas of America. They all were subsistence farmers first and foremost. My GGFather worked for the railroad. It paid well for the day but they still produced all their own food. My Grandfather was a steel worker from the 30’s-1970 and he still to the end produced more food than he ever consumed.

Based on your comment I would have to consider my Grandfather a little crazy as he was obviously engaging in unnecessary/backbreaking work for crappy pay when he tended his garden but there is a payback you get in the ‘doing’.

If you think you are going to be happy doing the same job when you are ‘paid enough’ I fear you are only kidding yourself.

“The only lifelong, reliable motivations are those that come from within, and one of the strongest of those is the joy and pride that grow from knowing that you’ve just done something as well as you can do it.” –Lloyd Dobens and Clare Crawford-Mason

You can’t work your way up in an organization where the business model is attrition. I’m not going to surprise anyone by pointing the finger at Walmart, which has insanely high turnover rates and likes it that way. But I’ve also gone through job hell and had to be wary of burner sales positions with intentionally nigh-unreachable quotas, and worked at a real estate rental firm where they paid us only in commission and didn’t expect us to last long or make a living at it. Transactional sales have no career traction if they don’t need you to maintain the relationship with the client.

Rick Smith: Your analogy makes no sense. If your Grandfather was, indeed, paid relatively well as a steelworker, then he did not need to grow his own food. He chose to do so because he enjoyed the work. Many people do work, even backbreaking work, because they enjoy it – but that doesn’t mean they can always make a living at it. I’m sure your grandfather’s quality of life, as well-compensated steelworker who grew food on the side, was immeasurably better then a subsistence farmer’s. This has nothing to do with the nature of work today.

To Aaron’s original piece: There’s a lot of interesting stuff in there. But the elephant in in the room – that today’s “McJobs” do not pay well enough to support a middle-class lifestyle, or even a family – goes unremarked upon. If Wal-Mart in 2014 paid like US Steel in 1948, we wouldn’t be having this conversation. I don’t know that such a thing is even economically feasible, but you simply cannot comment on the decline in the value of work without commenting on the decline in the value of the worker.

The piece also makes some frankly bizarre statements about millennials. I’m 29, and I am one, and I can tell you that Strauss and Howe’s “Generations” theory had no impact whatsoever on my upbringing. I wasn’t even aware of it until a few years ago, and I sort of regard it the way I regard astrology: interesting to think about, but basically bunk.

What IS true about millennials, and which Aaron does discuss, is that we were raised with the idea that we should find our work personally fulfilling. Youthful dreaminess was not invented in the 1990s, but many of our parents did give us the idea that we should pursue goals for personal, intellectual and emotional fulfillment and that meaningful work would follow. This was by no means universally true, but for people whose parents are American baby boomers, it was certainly the norm.

So, now that my friends and I have been out in the working world for some time, how’s that going? Not so well, as the media loves to point out. But what the media doesn’t seem to like pointing out is, most of us are adjusting. The millenial attitude toward work that I read about mirrors how my friends felt about work when we were college students, not now, as we are entering our thirties. Most folks I know take pride in the work and try to use their talents to make a buck, but were long ago disabused of any notion that work does not involve trade-offs, and tediousness, and annoying supervisors, and stuff that you would never do if they weren’t paying you.

The millenial generation saw our parents’ outsize expectations for us crumble (due to the economy and due to the fact that, well, not everyone can be Mark Zuckerberg), shrugged, and said “well, we’ll do what we gotta do.” Unfortunately, this doesn’t make for very good alarmist trend pieces in The Atlantic, so you mostly hear about the small minority that was privileged (or misguided) enough to keep the delusion alive.

Aaron, I appreciate your thoughtful perspective on the inherent value of work. BTW that Larry Bird ad was for Prodigy, the defunct online service provider. I couldn’t find the video online, but the companion ad featuring Aretha Franklin is on YouTube. See a critical review of the spots by Advertising Age at http://adage.com/article/snapshot/prodigy-ads-warm-deliver-pitch/60344/.

Vin – maybe I wasn’t clear enough. My apologies if that is the case.

I wasn’t trying to make anyone wrong only to show that the simple tasks that give our lives meaning should not be based on accepting the premise the only value we get from the work itself is the wage.

That side of my family were subsistence farmers 100 years ago and for the ones that didn’t leave Appalachia since the steel mill is gone and the coal depleted and the railroad has automated operations they are subsistence farmers again.

But now they get a check or two. Self-esteem wise I don’t think they feel better about themselves than their ancestors though they have MUCH more stuff in almost any way you would measure it.

You end your note with : so you mostly hear about the small minority that was privileged (or misguided) enough to keep the delusion alive.

Curious which did you think applied to me?

Great article. It may rival one of your Chicago articles for comments.

Re the Millennials: What you and the two authors of the book say of them is no doubt true. But I think you/they are addressing a sub-set of the generation. The author’s conclusions are based on evidence that is mostly anecdotal. They lived in a suburban Washington “super zip”. These kids are exceptional — no doubt about it. However, they (the authors) are blind to a segment that is at least if large, if not significantly larger. This is a rapidly growing white underclass. There has always been a white underclass; but traditionally it was a rural phenomenon. It has now invaded urban and suburban America. Charles Murray, in a book I highly recommend, “Coming Apart”, estimated the size of this class to be approximately 20 percent of the white population. This population will be just as exceptional in its abject dysfunction.

Being an early boomer, I can relate to a lot about what you say about working as a teenager. I often ask guys “when can you remember not working?” The usual answer is something like 14 or 15. The “greatest generation” considered providing anything beyond food, clothing and shelter as purely optional. An entertaining follow-up is: “tell me about the jobs you’ve had?” Mine include boat bailer, fish cleaner, and donut maker. I guess “swabby” for the USN was a job too.

Rick – no worries. Your original comment just read a little “kids these days, they don’t want to work!” to me, but I now see that that’s not what you meant.

Regarding your question, I suppose I wasn’t clear in that my first paragraph was a response to your comment, and the rest was a response to Aaron’s original post. So I wasn’t thinking of you when I wrote that, and, frankly, I couldn’t say which group you’d be in seeing as I don’t know you. I will say, though, that the “groups” I reference are permeable. I’m not a fan of dividing people up into all-encompassing categories.

Hope this clears it up!

Interesting thoughts. I have several reactions:

1. The generational theory is one that has struck a chord with me. I’m not as predeterministic as Howard & Strauss, but there’s something to be said about a cultural pendulum functioning somewhat like an economic one-where generations cycle from more communal to more individualistic

2. Ironically, you kind of argued Howard & Strauss’ theory in your post. You state that parents became “helicopter parents” and changed they way they parented their young. I don’t think this was a direct result of Howard & Strauss-I only myself heard of them a few years ago-but more of the cultural pendulum swing. But this cultural change is exactly what they were referring to.

3. I also think that the advancement of technology and lifestyle has something to do with it. WW II and the automobile changes this nation forever. After a while, the solutions to the old crises-global war, depression, economic isolation- don’t work for new ones-global terrorism, climate change, income stratification. When that happens, things get mixed up. I think the whole Tea Party battle is a direct result of this-people tend to fall back on what they were raised to think works, especially in times of stress. Boomers fall to rugged individualism-ironically incubated on the street of San Francisco in the 60’s-now transposed onto our current problems-i.e. get that “collective government” that caused Vietnam and then Iraq and the financial meltdown out of the way and everything will work better. Millennials, raised with current problems, are looking at it through twitter-fed eyes-they see different solutions. Theirs is a strange sort of blend-exalting the individual amidst a communal world that can band together to solve any problem. The Millennials will end up winning that battle just by virtue that they will outlive the Boomers.

4. I do think that our culture is becoming a bit more European, slowly. More renters of choice, more thought to what a person is outside of work. The Protestant Work Ethic is being slowly replaced with a “Holistic Person Ethic”. There are a ton of good and bad things about this, which would be too lengthy to get into here.

5. I wonder if this view of work isn’t starting to change-given that we have a great shortage of jobs. I don’t know that defining yourself as more than work is bad. I do however, think that demeaning certain jobs IS bad. But when all of your friends have “McJobs”, that changes your view quickly. I have to admit-I once applied to work at McDonalds when I thought my regular summer college job in an office was going to fall though. I think I cringed so much that they never even bothered to call me back. Today, if I had to, I would be much more willing to do that job without a hit to my ego, given how many people don’t have jobs at all.

Very well said Vin!

I appreciate your efforts to avoid segmenting/labeling.

I think so often we miss each others point because we don’t try to bridge the unique individual experiences that have brought us to this place where we now stand.

Hope that makes sense, not at my sharpest today!

BTW this blog could be considered a “self-actualization” of sorts beyond work for you Aaron and those that post regularly.

Aaron,

Do you honestly believe “Millennials began to be told from nearly birth that they were destined to be nothing less than the salvation of America…leading us forward into a better brighter future” is even remotely reflective of their upbringing? How many Boomer parents do you think ever even heard of Howe and Strauss?

You’re mischaracterizing Tocqueville’s preindustrial America. In that era, few Americans were employees; most were yeoman farmers or independent farm laborers. It’s true that such grueling labor was respected, but self-rule was highly-valued. That sort of “self-actualization” was also apparent in the inventors and businessmen of the industrial era, who were notoriously difficult to hold onto. For the less-skilled, industrial employment compensated for the lack of self-rule by enormously out-paying self-employment; even then you constantly read of the difficulty of domesticating the industrial workforce. Now that large-scale employment no longer offers much of a wage premium, it shouldn’t shock us that people have shifted somewhat back towards self-actualization. Employment that continues to carry a large wage premium is either fairly new on the scene (tech) so the culture is still adapting to its availability or it’s defacto positional and most Millenials know they won’t make the cut (employment in medicine is artifically capped and big law/finance/mgmt/consulting are just positional naturally).

Combined with those shifts, you’ve already mentioned the snapping of career leaders and the growing college premium. Is it any wonder that Millenials with options avoid McJobs like the plague? They’re obviously dead-end and won’t support the normative lifestyle; that wasn’t true for prior eras’ unskilled work. Why wouldn’t that be sufficient to lower such jobs’ perceived status? I don’t understand why you believe that “the problem is not inherently an economic one.” It’s most certainly not the nature of the work that has Millenials avoiding McJobs, considering they do work of that nature for free in volunteering or internships.

I see a strong parallel between this and your Rustbelt analyses, where I see powerful external economic changes as both the obvious and sufficient explanation for resulting cultural shifts, and don’t really understand why you clearly understand the economic changes but then choose to dismiss them and treat the cultural reaction as causal. Occam’s Razor, Aaron!

Finally, “the sacralization of their own personal desires” long pre-dated Millenials, it was really about the Boomers (see divorce rates, Bowling Alone, Wall St, the Reagan Revolution, or your very own reference to hippiedom). I see very little reason to think Boomers/X/Millenials are any different in their emphasis on personal desire; the main novelty is that Millenials were taught that their personal desires shouldn’t be limited to the financial and should include a desire to contribute to general welfare. Sure, those “shoulds” are only superficial for some people, but it’s strange to implicitly criticize the shift, which is probably just a healthy Boomer response to their own regrets about selling-out.

I should add that I see the Xers as never having been quite so indoctrinated as to what to desire in the first place (your latch-key stereotype)- in my experience Xers don’t focus on finances as much as Boomers nor on social welfare as much as Millenials.

This may seem a minor point but the incredible rise in interest rates at that time lead to a significant shrinkage in inventory in many areas. The auto or hardware parts store that prided itself on a complete inventory quickly realized that the move to limited stock to reduce investment was the wave of the future. Thus, multiple radiator hoses were replaced by one with “cut here” marks for multiple fits, slow moving stock numbers were cancelled, clothing sizes reduced, etc. Fortunately the internet has lead to a replenishment of odd sizes, special SKU’s, and other now “special order” parts.

Really, the old tropes about Boomers are, well, old.

Since I took a swing at the “Millenials lack a work ethic” (since the ones related to me don’t), I’ll take a swing at the Boomer generalizations too.

Note that a higher percentage of Xers and Millenials are suburban residents than Boomers. This, in a nation where “suburban McMansion dwellers” is code for “money-focused, self-absorbed people”.

Boomers created the huge boom in the social welfare non-profit world, and mis-characterizing the whole generation as individualistic and self-centered is a huge overstatement.

Note that the US’ richest Boomer is also its biggest philanthropist, and that he has encouraged others similarly situated to “take the pledge” to give their fortunes away.

Perhaps a minor point, but isn’t it a key feature of the McJob that you have to clothe yourself, often literally, in an undignified and oppressive corporate culture while you are working it? The uniform/hat/name tag, the wrappers, the logos, the silly names for the products (“Whopper”), the shoddy quality of the products themselves (“Where’s the beef?”). There’s a qualitative difference between working a menial job in a “real” restaurant and flipping a McBurger.

Not sure that people feel low-level jobs per se lack dignity; it is the corporate culture or branding element that often removes the dignity from the job.

Excellent post, Joel. The dignity of work is something that Dirty Jobs’ Mike Rowe espouses. Forget self-actualization; do something challenging and well appreciated instead.

I often think of the two women in England who recently quit being lawyers and have become plumbers, and love it.

The book Boys Adrift argues that you can’t entice today’s young into the trades. The notion of going to college is too ingrained as a path to a successful life.

I’m with Julie on the idea that it’s the type of work, not the pay, that can make McJobs so unpleasant.

The difficulty of getting the young to be attracted to the trades may be summarized by this observation I’ve made in the Chicago metro area: in the more upscale higher income regions, the trades tend to be highly bifurcated.

On one hand, you have the upper-skill groups like electricians, operating engineers, ironworkers, pipefitters who can earn well over 6 figures with enough overtime. However, apprenticeships seemed to available only to those who know somebody. Thus, if you are Joe on the street, maybe even Easy Street with high-earner professional parents, you are probably not going to have a familial or peer connection to the trade of your interest – a variation of the all-too-familiar “we dont want nobody nobody sent” connundrum. Then you have the lower-skill trades – drywall, painting, road markings – who to the common observer have looked to be taken over by illegals/hispanics (depending on the extent to which said observer makes assumptions based on stereotypes). These can be cliquish as well (for example immigrants and American-born descendants from one particular Mexican state, Nuevo Leon, tend to dominate the laborers local in Lake County, IL) , and are probably the only employment subcategory with blatant discrimination based on ethnicity and language.

I think the youth of today are indeed looking with skepticism at the “college is necessary” meme, but real and perceived barriers probably keep them at arms length from the trades. Tech and entertainment seem to be the only truly open avenues which may not need such a high degree of credentialization enabled by traditional college education.

@urbanleftbehind’s point rings true. Many millenials are flocking into “dirty jobs” like urban farming and or butchering- even when profit prospects are low.

This generation seems keenly aware of how transient traditional corporate “career paths” are. My guess is quite a few would “sell their souls if they thought it was a realistic plan.

I agree with the comments above pointing out the economic drivers of this broader phenomenon (general devaluation of unskilled work in American society) but will comment a bit more narrowly on the cultural side.

I’m 28 and so solidly in the Millenial bracket, and reading the section about how we’ve been raised left me scratching my head. To the extent that Aaron is right about how Millenials view work and what their parents emphasized, I have to wonder if this isn’t a regional or big-city phenomenon or something.

I’ll start by saying I grew up in Kalamazoo, MI. My parents were both professionals in education administration with MAs, born 1950-1951.

When I was 15 my parents told me it was time to have a job. They knew somebody who ran a home inspections business and needed someone to do the menial task of typing up report forms on carbon triplicate using a physical typewriter. So I went there every day after school and every day during the summer for a few years and did that. Going down my list of friends in late high school, they spent collective decades taking orders at Starbucks, cleaning up and manning the pro shop at a golf course, working as a clerk at a local scrapbook supply store, delivering burritos, roofing houses, filling in excel sheets of data at an engineering firm, and even the stereotypical serving hamburgers (Burger King and Culver’s) or bagging groceries (Meijer). And I’m sure I’ve forgotten many other people and their odd jobs since then.

In other words, the line about “…the notion of work as something you just have to do, something that is part and parcel of being a fully formed adult, no longer exists.” rings completely false. My entire peer group was raised with the impression that unless you worked, no matter what the work was, you were lazy and/or a failure, and that part of growing up was having a job. And we all worked and continue to work. Admittedly, I didn’t become a home inspector.

So, maybe Kalamazoo is special in some way I don’t know about, and I’d be very interested to hear if anyone thinks there’s reason to believe that’s the case. But in my personal experience, there’s been little loss of the emphasis on work as inherently valuable, character-building, worth doing even if it’s tedious etc. It’s certainly accompanied by the sense that one should aim higher, and that it would be unwise to plan on supporting and raising a family by serving lattes. But I doubt my generation invented that.

Since this whole thread paints with a broad brush, I do see a trend among millenials to want to go it alone, avoid working for the “man” etc. But I don’t see a trend towards slacking. If anything this group is more realistic about effort and sacrifice- more willing to live in small apartments, ride a bike, have roommates & and delay gratification to reach their goals.

Look how badly retailers targeting this group are doing. Student debt and underemployment are a huge factor, but something deeper may be happening.

Aaron,

I find your analysis of how what unions built for workers in the mid-20th Century interesting, because I do think a lot of what we consider “the American Dream” of the “middle class” is ultimately unsustainable in both an economic sense and an ecological one. Unions certainly deserve a lot of blame for many things that are wrong with our society, from the over-building of highways, to the ideal that everyone should own a car and live in the suburbs on their middle-class income, to the expansion of military industrial or prison industrial jobs out of political deal-making between politicians and union leaders (I grew up around Philadelphia, so I know that the local Republican who was very pro-war and not progressive at all drew a lot of union support from Boeing workers, and I’ve heard that the Portland, Oregon efforts to limit highway expansion and build bikes and transit very much came up against union leaders there that wanted highways as a jobs program).

That said though, do you really think it’s fair to say that there was nothing for workers to gain in the ’60s or ’70s? Dissident union groups helped to fight for racial equality at the workplace and off, for gender equity, job safety issues, and so on. As much as I feel like the average UAW worker living in a detached suburban Detroit house with two cars might not have really gotten what was right for the country, I also really value groups like DRUM that were self-organized by black workers to fight having to be the ones who were stuck doing the dirtiest and most dangerous jobs in factories. And as someone who’s worked quite a few low wage jobs, I can say also that I think today we have a real need to expand on the worker protections found in the NRLA and so on, because those protections on paper don’t always amount to workers being able to make free choices about representation (I also think workers should be free to choose among a variety of unions instead of just one, like in Europe, and I would support being able to “opt out” if it were made easier to “opt in” through card check, faster elections, etc.).

So I think your point that unions can be a detrimental force in the American economy is well taken, it’s just a question of whether that critique is attached to the right solutions.

James I agree and it is all a question of balance. I worked for a union company for nearly 30 years. By and large our employees are highly regarded. But the fact was regulation created a virtual goldmine for us. The early opportunities deregulation brought helped cover some of the internal mistakes we made in the rapid growth we saw. Today we are now basically a commodity. Tough to differentiate in a plain brown wrapper.

Customer is king and queen and when you have a union / management group you tend to have a buffer between you and the customer. My experience was it works to the detriment of all 3 parties. But you are correct it can work not sure it is optimal relationship but I don’t have an optimal one to offer either.

In my book it really comes down to everyone getting more or all parties get less. You either make the pie bigger or you spend increasing amounts of time and energy trying to figure out how to precisely divide that finite pie.

Doesn’t sound sustainable. Almost definitely not self-actualizing.

btw – I know the lack of dignity comments are not meant to be funny but I can assure you that things weren’t all warm and fuzzy in our days as boomers. I did ‘something’ most of my life. Papers till I was 16 then a busboy. They weren’t real interested in our feelings or self esteem then either.

Nice post, but you spent pages pretty much saying what many people have more succinctly been saying for a long time:

Americans have gotten lazy.

While I appreciate your use of Tocqueville as a springboard, it doesn’t entirely acknowledge that his trip along the Ohio River, where he compared industrialized Cincinnati to agrarian Kentucky. He was highly critical of what he saw as an almost landed gentry in the slave-owning class of the antebellum south, where he believed that, through forced labor, the southern gentry developed a stigmatization of work not unlike the European aristocracy. The result, as Tocqueville saw it, was that the “Union” (where hard work yielded clear monetary rewards) absorbed virtually all of the economic growth that accompanied industrialization. This by no means degrades your observations of what might the emergent and prevailing ethos among Millennials.

Great article, and great comments.

A few reflections:

1. Tocqueville, bless him, got many, but not all things right. Contemporary accounts from pre- and post-Revolutionary times up through Civil War reflect a strong class bias that was to a material effect based on one’s occupation, especially once you set aside farming. I’m not sure Tocqueville’s observations are the right basis for comparisons.

2. If you’re a fan of 1930’s-40s movies, you can see in a heartbeat a significant class distinction, recognized by all, between judges, professors, lawyers, doctors and “tycoons” on the one hand and blue collar workers on the other. These were not jobs that were created equal. In this respect, Hollywood was reflecting, not, directing, American perceptions.

3. It’s difficult to make sense out of any inter-generational analysis without factoring in the biggest demographic shift in the last 100 years — the entry of women into the work place. This is a book, not an essay, and, I suggest, would affect this analysis in all kinds of surprising ways, right down to what it means to “be a man,” and the centrality of work — any type of work — to that concept. (That’s not the heart of it, just an example of probably a dozen ways that women’s large-scale entry into the workforce changed the meaning of work.)

4. Aaron, if you haven’t read it lately, I urge you to reread Studs Terkel’s “Working,” and write a post-script to this article based on your reactions. Terkel’s book came out during part of the period you’re talking about, and, at least to me, still provides some of the best insights of the watershed years of the 60s-70s.

5. As an early boomer, I wasn’t that different from my millennial nieces and nephews. I hated the idea of going to work, at 16 (Burger King). My parents told me I was lazy, that this was Life — welcome to it — that all work is noble; that my father worked in a root beer stand when he was 11, etc., etc. They said that Burger King (and the follow-up jobs house painting, loading trucks at UPS, landscaping at a cemetery) would teach me about life and “real people.” They also told me that I had no choice about college. If I didn’t go to college I’d end up in a dead-end job like Burger King. And all the guys I met doing the McJobs of the 60s called me “college boy,” … BUT they also told me to finish college or I’d end up like them. This doesn’t resonate to me as being that foreign to what my nieces and nephews have heard and experienced. I’ve forwarded your essay to them, and am eager to hear their reactions.

6. I’m suspicious of intergenerational comparisons if anyone involved is still living. The “Greatest Generation” didn’t get that characterization until 1998 — a lot of ’em were in their 80s by then, and their kids were in their late 40s/early 50s. Right up until they were redeemed, the Greatest Generation was the generation of the atom bomb, 3-martini lunches, segregation, air pollution, materialism, conformity, suburban flight and pro-war. Based on the swift about-turn, I’d suggest it’s a little early for the kids of boomers to be writing the definitive characterization of the boomers. AND vice versa.

In any event, great article, great comments!

Thanks!

Ironwood

Great article, thank you! You have a new follower.

I’m not sure about the quick and simple characterization of “the good old days” when most work was considered honorable and everyone could earn a living wage. I don’t really think the thesis is well supported by just making the statement that it always _seems_ like CEOs used to start out in mail rooms.

I feel like this shortcutting might miscategorize the social change you are discussing as a new thing rather than a lateral shift from the prior status quo, because the previously stigmatized jobs are ignored in the original premise.

I’m not sure, but it feels more to me that our definition of honorable has shifted than that our desire to work an honorable job has changed.

Great, thought-provoking article. I just discovered your blog and look forward to following it regularly.

To pick up on some of the previous comments – Tocqueville was writing at the beginning of the Industrial Revolution. It seems unlikely that the dehumanizing effects of working a rote, repetitive and often mindless job in a factory had become fully evident. I haven’t studied it but in reading Walter Isaacson’s biography of Benjamin Franklin, and more recently the book Founding Brothers, that prior to the Industrial Revolution the nature of work itself was much different.

I’ll echo Ty Fujimara – I think people’s desire to work an honorable job hasn’t changed so much as that jobs that actually acknowledge the humanity of the worker have largely disappeared. Whether it is working in a factory or a call center or as midlevel management in a huge insurance company, most available “jobs” these days seem to be rote, repetitive and thankless, offering little in the way of career advancement or any measure of personal satisfaction.

The pervasive notion that the so-called “Free Market” can solve all ills and a relentless focus on short term ROI has completely devalued anything that isn’t outcome based and demonstrating immediate results. While this has practical effects on any type of work that happens in a “human economy” that depends on human interaction – the corporatization of the university system, the dismantling of public education, a dysfunctional health care system and the decimation of arts, humanities and scientific research – it has the larger effect of demeaning the entire notion that the quality of one’s life is improved through meaningful work, not merely material gain.

This past year I started a project about the economics of cultural production in the performing arts (www.brooklyncommune.org) where we discovered a text from 1965 by two Princeton economists, William Baumol and Bill Bowen, called “Performing Arts: The Economic Dilemma”. It was startling how much was still relevant and how little had changed. The key insight relevant to this issue is the idea of “psychic income”. Baumol and Bowen argue that in a healthy economy people will take work with less real income in exchange for “psychic income” – the emotional and psychological satisfaction of doing something that engages you more deeply than repetitive labor, or a so-called “day job”. For most Americans these days that is not an option, because wages in the arts are so spectacularly low – and artificially depressed because of the disproportionate amount of workers who receive subsidy through wealthy family or spouses.

The point being that I am around a lot of millennials who are just entering the workforce and some of what you say is true – they’re often reluctant to do grunt work, they want to skip to the fun, high-reward part. But I wonder how much of that is a function of their age (I was pretty job-averse at that age, though I loved to work hard on my own projects), their “generation” or the economic privilege that enables them to deliberately enter a low-wage field.

Still, the desire for work that provides psychic income is not a rejection of work per se, so much as it is a deep yearning for something all too often absent in our cultural discourse: meaning.

We are have moved from a “job” economy to an “independent contractor” economy, but our legacy systems are still designed for an Industrial world where people will have only one employer – maybe 2 or 3 – over the course of their lives. Millennials will have something like 20 or more “jobs” over the course of their careers. More likely they will spend most of their time freelancing, going from project to project. The future of work looks far different than it has been for the past 200 or so years.

I think essays like yours can help spark some great conversations about what we want that future to look like.

Thanks for the great comments.

I do want to stress again that from my perspective the changes in attitudes are a result of economic change, not a cause of it. So I agree with many commenters on that point. But my hypothesis is that producing the will to change the current trend that is eviscerating the middle class, we need to first change our attitudes. If we don’t see certain jobs as worth doing, we will never muster the will to upgrade their pay, working conditions, etc.

@Andrew Horowitz,

Your statement that, “We are have moved from a ‘job’ economy to an ‘independent contractor’ economy, but our legacy systems are still designed for an Industrial world where people will have only one employer – maybe 2 or 3 – over the course of their lives. Millennials will have something like 20 or more ‘jobs over the course of their careers. More likely they will spend most of their time freelancing, going from project to project. The future of work looks far different than it has been for the past 200 or so years” is dead on.

Companies are looking to “just in time” labor the way the looked for “just in time” materials. Our institutions are woefully set up for this. Obamacare was a game try at de-linking insurance from a job (a necessary thing to do), but seems to have gone badly wrong. This was part of my call to unions to reinvent themselves. Unions as they were conceived were mostly linked to stable employment relationships. The trade unions and their hiring halls were an exception. That’s actually a model that’s already been set up for the contractor economy for decades now. There’s no reason it can’t be adapted to really create some type of a stable structure under which workers can navigate this new reality. That would put organized labor on offense instead of defense. Technology, with its existing tradition of contractors, might be a good place to start with that.

not to promote McD and similar but the view that McD is really an effective and very cost effective job training program is essentially correct. They teach people the basics of work, i.e. show up, sober, on time, prepared to work, satisfying customers, getting supervision, and a minor monetary award. Then move up to a real job as opportunity and capability permit. I wish the proposed Obama job training programs could deliver that. The fact that the coffee and biscuit I will get at 0330 tonight is not my favorite product is not as important as the fact it will be readily accessable at a low price and adequate quality.I PAY FOR THE BISCUIT, NOT THE TRAINING.

Hope I’m not to far off topic here but I believe it relates to the issue of ‘jobs without dignity or respect’.

One of the things I would like to see is associations of small local businesses. A small business exchange as it were to give local businesses some economy of scale to improve their growth rates and profitability.

They will never be on an equal footing with the big Corporate boys but through association and combined purchasing should have the buying power to leverage.

I think people find it easier to work for small businesses because they tend to not be so bureaucratic and top heavy. Small business the owner is likely out working the floor.

These could also become incubators for aspiring entrepreneurs. I have to agree with the comment about McD that they do teach you the basics of what you need to add value to a position. If you aren’t adding value you are not sustainable economically.

The beauty of small business is it returns more to the community in wages and retained profits than chains contribute in total. Strong small business means jobs with greater appreciation on the part of the employer and employee. It is true large corporations engineer all of the spontaneity and creativity right out of people. In effect leaving you with the lowest return on your labor, financially and psychologically, and the dollars captured by the corporation flee the community.

A job with dignity is one where you feel like you make a difference. In Small Businesses everyone makes a difference.

Aaron,

Completely agree about unions being able to offer many services that used to be provided by lifetime employers.

But saying that you agree, economic changes caused a cultural reaction but now we need to change our cultural reaction to undo the economic changes seems exactly backwards. The cultural reactions are perfectly rational given the economic context we’ve created.