[ Buffalo’s Chuck Banas is a great thinker, doer, and writer on urban matters. He graciously allowed me to repost some of his articles, and this is sadly the last one I have on file. It was written in 2009 and so some of it addresses what was going on at that time, but the perspective remains relevant, even if sprawl is not your issue. – Aaron. ]

I’m certainly not the first pundit to comment on the recent economic meltdown, and I sure won’t be the last. But there is a side to this crisis that almost no one is talking about, perhaps because it hits a little too close to home–literally.

The two primary assumptions embedded in our national dialog seem to be that (1) like the dot-com bust of 2000, the problem is a fairly recent phenomenon caused by the latest round of irrational exuberance on Wall Street, and that (2) worst-case, we’ll all be able to go back to the old borrow-and-spend way of life in a couple years. Both are symptoms of denial that make it impossible to address the larger problem.

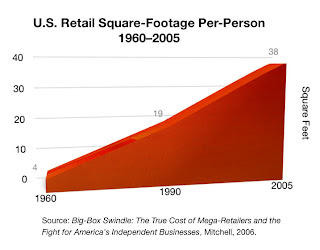

This crisis is not simply about bad suburban housing debt. By some estimates, more than one-eighth of the retail space in the U.S. will be sitting vacant within a few months. The graph at right illustrates that situation very clearly. I’m thinking you’ll be shocked by it. Whether or not that’s the case, kindly indulge me and read on.

This crisis is not simply about bad suburban housing debt. By some estimates, more than one-eighth of the retail space in the U.S. will be sitting vacant within a few months. The graph at right illustrates that situation very clearly. I’m thinking you’ll be shocked by it. Whether or not that’s the case, kindly indulge me and read on.

The proverbial elephant in the room is the amount of sprawling, redundant public and private infrastructure we’ve built since the end of World War II. This exodus to the suburbs quickly resulted in the hollowing-out of major parts of older cities and towns. Furthermore, the overwhelming majority of this development is automobile-based. Places to live, work, shop, and play are intentionally separated by vast distances. Low-density, separated-use zoning has ensured that there is far more infrastructure to maintain per-person than in older village, town, or city neighborhoods.

For this suburban system to function, residents are required to own, operate, and maintain a car. Or two. Or three. Nobody knows this better than the typical suburban family. While car ownership is expensive enough, it is not simply a matter of gasoline and monthly payments. The automobile incurs another immense cost: cars can’t operate without lots of flat, smooth, publicly-funded road infrastructure (read: roads, highways, and the accompanying electric, gas, water, and sewer utilities).

All of this is stupefyingly expensive. These indirect costs constitute the majority of the expense, yet remain invisible to most people–spread-out in the form of local, state, and federal taxes, or camouflaged as municipal bond debt or various other forms of government debt. So in addition to being redundant, this means that suburbia is a doubly expensive living arrangement.

The other point that I’m trying to make is that the migration of wealth to the suburbs has not been a free-market phenomenon. Customer choice is only a small part of the equation, or this wouldn’t have happened in virtually every American city at the exact same time in the exact same way. Which, of course, is exactly how it did happen.

I assert that much of the economic crisis we’re seeing today is simply the end result of decades of bad decisions driven by bad economic, transportation, housing, and land-use policy.

A mercifully short history of sprawl

To understand the sudden suburban migration of the post-WWII period, and what it means for us today, some historical perspective is required. Happily, I’ve done my best to keep it short.

Powerful enablers are required for such a sweeping thing to happen. Post-WWII suburbanization was caused not simply by the availability of the automobile, or postwar housing demand, but by a converging set of public policies that resulted in blighted cities, towns, and villages, as well as an uglified, overdeveloped countryside. Without getting into gory detail, the major enablers included the national highway system, subsidized government loans for new suburban housing, the often intentional withholding of needed capital to renew older neighborhoods, and notoriously destructive urban renewal projects. These policies, and others too, amounted to the most massive outlay of taxpayer subsidies and incentives the world has ever seen. The ’burbs were not built by chance. Or merely by customer choice.

This is not to say that these policies weren’t well intentioned. For the most part they were. But they were also largely naive and shortsighted. However, at the time, they were seen as necessary to address some of the largest concerns of the day. Foremost, this involved the very real possibility of lapsing back into a depression as American industry demobilized. These fears were inflated by the vast problem of re-employing the nine-million-or-so men and women formerly in uniform who suddenly found themselves out of a job.

Keep in mind also that after an almost 15-year period of depression and/or war, American cities were not in great shape. During that time, there had been little public or private investment, and cities still contained all of the noxious, unpleasant activities of the industrial age, accompanied by virtually none of the environmental protections we take for granted today. Also, during the war, hundreds of thousands of southern blacks had migrated to northern cities hungry for defense labor, adding a racial component to the issue. Finally, the steadily increasing population of cities had created a housing demand, especially among the middle class and the millions of young war veterans newly empowered by the GI Bill.

To avoid the obvious potential mess, the federal government decided to create a large set of subsidies and incentives for new construction and new land development. All at once, this would help alleviate housing demand and instantly create thousands of jobs in the construction trades.

At the same time, cities, perceived as overcrowded, dirty, and dangerous, became the victims of the so-called ‘urban renewal’ programs of the 1950s and 60s, a process by which many otherwise viable neighborhoods (most often minority) were demolished entirely and replaced with a smattering of low-quality publicly-subsidized housing projects. Families, businesses, and other community institutions were uprooted, neighborhood relationships were destroyed, and most residents were forced to relocate to other neighborhoods–many of which were, shall we say, less than welcoming. It is dfficult to overstate the amount of social stress and psychological trauma caused by this. Ever wonder about some of the reasons behind the urban race riots of the 1960s?

At the same time, cities, perceived as overcrowded, dirty, and dangerous, became the victims of the so-called ‘urban renewal’ programs of the 1950s and 60s, a process by which many otherwise viable neighborhoods (most often minority) were demolished entirely and replaced with a smattering of low-quality publicly-subsidized housing projects. Families, businesses, and other community institutions were uprooted, neighborhood relationships were destroyed, and most residents were forced to relocate to other neighborhoods–many of which were, shall we say, less than welcoming. It is dfficult to overstate the amount of social stress and psychological trauma caused by this. Ever wonder about some of the reasons behind the urban race riots of the 1960s?

Also under these programs, downtowns, waterfronts, and other older neighborhoods were mangled or obliterated by expressways and automobile-related transportation projects. It’s no surprise that urban renewal soon became sarcastically (and perhaps more accurately) known as ‘urban removal.’ All of this lowered the value of older cities, towns, and villages, and intensified the suburbanization subsidies already in place.

Primed and sustained by these subsidies, the suburban build-out has continued generally unimpeded in the decades since. It actually accelerated through the 1990s, driven by both cheap oil and a frenzied, anything-goes lending market. The map above remarkably demonstrates this. The red/yellow areas, amounting to at least half of the total colored area, represent the land developed from 1993—2001. The purple/blue is the land developed prior to 1993.

Think about that. At least as much land has been developed in this country in the last 15 years as in the previous 400 years of our history.

Not surprisingly, as people continue to move even further out, older suburbs have been experiencing the same problems of poverty, crime, and blight that city neighborhoods have seen. And so it goes.

The sprawl bubble

Today, the resulting problems are vast, intimidating, and painfully obvious. Yet it’s hard for most Americans to discern the problem, let alone see a way out of the woods. This is not only because we’ve got so much of our collective wealth tied-up in this system, but because suburban sprawl has become so culturally identified with the postwar “American Dream.” Indicting the system that produces sprawl is often seen an indictment of our very way of life.

And dissing the American Way is blasphemy, brother.

It’s therefore no wonder, though no less maddening, that we can’t seem to have an intelligent public discussion about this. It’s hard to broach the topic in public without really pissing someone off–often to the point of violent irrationality. Believe me, this is not a subject you want to bring up with strangers. Or in-laws. I know.

In any case, we’ve now got this glut of public infrastructure, most of which is obscenely expensive and redundant. Much of the older stuff has been in deferred maintenance for decades because we’ve been too busy trying to pay for all the new stuff. Accordingly, public debt is astronomical. In addition, the amount of private debt has never been higher, with average personal savings essentially zero. This is due in part because so many people have taken advantage of exisiting housing subsidies to buy homes they can’t afford and live lifestyles beyond their means. (Of course, there are other things that have contributed to this situation, but I won’t delve into all of them here.) The bottom line is that there’s no financial slack left in the system. State and federal governments, municipalities, banks, businesses, and individuals are all strung out on various forms of credit, because we’ve been collectively attempting to finance a way of life that is unaffordable and ultimately unsustainable.

This brings us back to the chart at the beginning of the article. If you didn’t see the significance the first time, you may want to look at it again. A simple measure of the current financial crisis is evident here: In 1960 the United States had about four square feet of retail per person. As of 2005, that number had risen to 38 square feet.

Yep, that’s right. This number includes not only the underutilized retail square-footage in older neighborhoods, but also the speculative, overvalued glut of strip malls and big-box stores of suburbia. The ‘dead mall’ has been a familiar sight across the country for a while now. Dead subdivisions are now common in suburban areas hardest hit by the housing crisis.

For a current comparison to other industrialized nations, see the second chart at right. While the U.S. number reported by this research is lower than the first chart (20.2 square feet vs. 38), it’s the relative difference between the U.S. and other nations that’s pertinent here. Note that other countries are still down where we were 50 years ago. You must then ask yourself these rhetorical questions: Do the Germans, French, or English live in some third-world consumer backwater? Are there overseas shortages of bread or iPods?

For a current comparison to other industrialized nations, see the second chart at right. While the U.S. number reported by this research is lower than the first chart (20.2 square feet vs. 38), it’s the relative difference between the U.S. and other nations that’s pertinent here. Note that other countries are still down where we were 50 years ago. You must then ask yourself these rhetorical questions: Do the Germans, French, or English live in some third-world consumer backwater? Are there overseas shortages of bread or iPods?

In any case, back to U.S. retail: As retail development follows residential, and both follow public infrastructure investment, one can infer that we’ve been sitting on a massive real-estate bubble for decades, propped-up by massive public subsidies. This is what I call the ‘sprawl bubble.’ In large part, this is the bubble that is currently bursting. This has implications for all Americans, not simply those of us living in far-flung suburbia.

Overdeveloped suburbs aren’t the only areas in bad shape. As we’ve seen, American cities, depopulated, disinvested, and impoverished, are not the mighty manufacturing centers they used to be. We’ve exported most of that activity to places like China, Mexico, Korea, and India. We’ve essentially become a country that doesn’t make things, simply existing as a market for other countries’ products. That’s why China holds a staggering–and ever increasing–amount of our debt. The Chinese must guarantee a market for all of their manufactured goods by propping up the value of our currency. Setting aside for a moment the irony that we’re now economically beholden to the world’s largest communist country, at least for now the relationship is a sort-of mutually-assured economic destruction.

Internally, much of our domestic economy is now tied to the construction and real estate finance industry which, using the capital provided by a runaway lending market, has been going gangbusters producing new suburban McMansions and strip malls–until quite recently, that is. It’s all come to a screeching halt, with the financial hucksters no longer able to hide the fact that much of this stuff has little or no value.

I’ve often wondered how long we’d be able to keep up this shell game. More and more, it’s obvious that this is a pattern of living guaranteed to bankrupt our country.

I may be wrong, but I’m thinking the piper finally needs to be paid. The scary thing is, for the most part, Americans won’t even admit the problem. I’m not an alarmist, but my fear is that we’re so pathologically attached to our system and its hallowed cultural myths that we’ll fight to the bitter end to sustain the unsustainable.

This post originally appeared in Joe the Planner on February 10, 2009.

Masterful. Take that, Joel Kotkin & Wendell Cox.

Andy, thanks.

I think this is a useful perspective to bring. But don’t sell Joel and Wendell short. Those guys have important if sometimes unpleasant to urbanist ears things to say. I think urbanists would be well-served to listen to them more seriously.

In any event, one thing I always want to bring here is a diversity of seriously argued perspectives. I don’t want only one viewpoint. That’s one reason I supplement my own writings with those of other people like Chuck who bring different points of view to the table.

Brilliant. Light that splits the darkness.

Mr. Banas ignores one HUGE factor in positing that “it didn’t just happen by choice all at once” mid-century: the end of WW2.

At the end of the war, there were millions of new families formed as “The Greatest Generation” came home from the service. There were, in fact, housing shortages in central cities and new units had to be built somewhere. Many of those men took advantage of both GI Bill and VA loan benefits.

Suburbanization had started in earnest in the US 40 or 50 years before that, and the massive postwar buying simply put the movement on steroids. The new houses weren’t in the cities.

I think it’s a lot less than clear that government policy “caused” these changes. Redlining and urban renewal schemes didn’t help, but neither factor was enough of a cause to explain it all. Likewise the Interstate system, as it didn’t start until the end of the Eisenhower years.

A separate issue is that the US is clearly over-retailed. That has the makings of another real estate disaster. We can’t fill every underutilized suburban space with an immigrant ethnic restaurant.

Urbanophile is a true marketplace of ideas. And the market is healthiest when participants take a position and boldly defend it.

It is my full intention, as William Strunk put it, to “make definite assertions.” I expect guys like Kotkin and Cox feel the same way.

When I rented my first apartment in Chicago’s Taylor street area I often told the owner of the 6 flat, who lived next door how cool his buildings were. We often discussed the rebound of the neighborhood and the near death experience of the 60’s and 70’s. Although He enjoyed how the neighborhood turned out by the late 90’s He could still not understand people from the suburbs’ fascination with city living, like it was a new discovery. As He put it, back then you had grandma, an aunt and uncle and siblings all living in a dingy crowded apartment with one toilet, one bathtub and nowhere to f**k (his words not mine). He said the neighborhoods were crowded, in disrepair, poor and often dangerous. There weren’t as many trees as there were by the 1990s and many alleys and sidewalks were dirt or broken pavers. So in that context, I could see where an 1800 SF cape cod in the burbs must have seemed like heaven on Earth to these people. There was a stigma, an embarrassment to living in these neighborhoods, especially for 2nd generation immigrant families who still had yet to prove they “made it”. The tract homes validated that yes indeed they had made it.

Chris: as I stated, there is no single cause of sprawl. But such a large phenomenon requires large enablers, and I attempt to lay them out here.

And yes, suburbanization did start in the early 20th century, but it wasn’t the kind of suburbanization we now know. It is entirely clear, and the accepted view, that post-World-War-II suburbanization was entirely different in scale and character than 1920s suburbia. And it was massively subsidized. Although the two eras are somewhat related, we really need to define the two differently.

So, as I put it in the post, sprawl was indeed caused by a perfect storm of public policy and other social and economic factors.

The main point of this article is the sprawl of the last twenty years, not before. The post-war concerns about over crowding were all addressed long before 1993. A real estate/highway/mortgage finance industrial complex took on a life of its own and allowed the tail to wave the dog by putting their interests before that of the overall economy. This is my understanding of Chuck’s point.

Marko: Yes, at the end of WWII there was an overcrowding problem in many of our cities, as well as industrial blight and a lack of investment — all items I covered in the article.

At the risk of oversimplification, the prevailing attitude after the war was this: one of the main problems with cities was all the people. If we could spread the population out, so the theory went, the problem would be solved. Thus was born our national de-densification program.

But even today, many decades after cities have been hollowed-out, we are still living under the influence of much of this policy, long after the end of its useful life. That’s the perniciously stubborn nature of laws and regulations.

Your example of Chicago’s Taylor Street is now the exception to most of urban America. Most areas of U.S. cities are far worse-off than Taylor Street. Heck, most are far-worse than Taylor Street was in 1945, with poorer and smaller populations, crumbling infrastructure, and collapsed economies.

But we got rid of all those pesky people. How long did we have to keep solving that problem?

“And yes, suburbanization did start in the early 20th century, but it wasn’t the kind of suburbanization we now know. It is entirely clear, and the accepted view, that post-World-War-II suburbanization was entirely different in scale and character than 1920s suburbia. And it was massively subsidized. Although the two eras are somewhat related, we really need to define the two differently.”

That’s my impression. I grew up in Forest Hills, NY which has at it’s core an early planned suburb of the early 1900’s.

Still, the deep pool of anti urban attitudes went way further back, laying the ground for what happened. I agree that without massive government involvement, these attitudes alone could not have cause the problem we have now.

My family is part Polish, where rural idealism still runs deep. In Eastern Europe, when you can, you get a little second house in the country and go on the weekend to tend the garden and pick mushrooms. Even so, the old cities survive.

What ever happened to living in the city and then buying a country house when one can, which if we didn’t have the sprawl, would be nearby?

“Suburbanization had started in earnest in the US 40 or 50 years before that, and the massive postwar buying simply put the movement on steroids. The new houses weren’t in the cities.”

There’s truth in that, but also a history of government involvement that goes further back.For example, the housing shortages in the cities not helped by the imposition of rent control. Robert Moses’s career started before the 1950’s and the goundwork was being laid.

Even the issue of “redlining” is a complex, chicken and egg problem. Dense minority areas like the Hill were victims of a lack of bank lending but was this because, these areas were black or because, there were already plans to “fix them.” It’s the same way today, in Pittsburgh where historic areas like the Hill and North Side are risky to invest in because of continuing threats of eminent domain takings.

It didn’t take a genius to know that areas that were dense and old were widely considered bad, not worth investing in and would be slated for removal.

Matthew Hall: I completely agree with your take on my take.

Residential real estate is grossly overbuilt, but commercial real estate is even worse. The United States now has “stillborn malls” to go with all the dead malls. Stillborn malls are shopping centers that have never been more than half-occupied, and have several storefronts that have never been occupied at all. (Atlanta is riddled with them.)

It’s time to stop subsidizing exurban crap and new infrastructure, and direct more money at renovating existing crap, and upgrading existing infrastructure.

Genius post, but I find Chuck’s responses to people’s posts herein a bit annoying-similar to going to an AA meeting when someone cross-talks. Nonetheless, a brilliant and provocative piece.

John: Thanks for the perspective. My family is Polish as well (both sides immigrated to Buffalo in the 1870s and 1880s) and the romanticization of rural culture is indeed deeply-rooted. It also helped that many immigrant Poles were poor agrarian peasants, and many of them intended (and even longed) to return to the family farms of the Motherland after conditions improved.

As for redlining “old” neighborhoods: many city districts were demolished almost solely because of high population density, and often for almost no other reason. In addition to poverty, mixed ethnicities and large minority populations were also considered evils, and these factors largely determined whether or not a neighborhood survived “urban removal.”

Demolition was often self-justified. An urban renewal district was so-designated years before actual demolition began. During this time, many residents resettled elsewhere, vacancies proliferated, and bankers were naturally unwilling to lend to those property owners that remained.

Tragically as a result, in Buffalo and many other cities, quite a few healthy neighborhoods (healthy especially by today’s standards) were obliterated.

The real estate bubble and its collapse, for residential and commercial/industrial space, is America’s financial Chernobyl. It will take at least one generation to sort out.

There’s the problem of surplus square footage. There’s also the problem of the development and construction industries bringing even more supply online. Third, there’s also the threat of more distressed real estate hitting the market.

Real estate poses a unique problem. Unlike an agricultural collapse brought on by a glut of crops, real estate doesn’t go bad. Plus, since the demand would have to be equal to or more than the 2000s bubble in order for prices to break even, there will be a glut of vacant buildings and sagging prices for years to come.

New construction is labor intensive, and being more standardized than reconstruction of existing buildings, an easy way to absorb relatively less skilled labor. Every recession I can remember has been met with calls to “revive” construction as a quick fix to unemployment. I’d ask if every recession since WW II led to an acceleration of sprawl in its aftermath?

Wad, real estate does “go bad.” The issue is that the only way to get rid of “bad” real estate is to spend even more on it.

Consider four types of “bad” real estate that have resulted from sprawl: the decrepit 100-year-old house in a near-downtown neighborhood, the decrepit 1st-ring suburban house, the run-down 1st-ring suburban shopping center, and the unsold lot in a suburban/exurban development.

There are several ways to deal with the 100-year old decrepit house. Demolition is cheapest. In a deteriorated neighborhood, the next-cheapest is demolition with a new build. Most expensive is bringing the house’s hidden infrastructure up to modern standards, which requires a “back to the framing” rehab. (Depending on the overally quality, desirability, and market in a neighborhood, these last two may reverse. But a frame-rehab will probably never be as resource-efficient as a new build, nor will it last as long.)

The second type of “bad” real-estate is the cheaply built plywood-sheathed house on a slab in the first-ring suburbs. When they become deteriorated (plumbing, heating, wiring, deck and sidewall delamination) there is no economical way to rehab them. Demolition is the only choice.

The third type is the old, original strip malls. These often find adaptive (and entrepreneurial) re-use because of their flexible nature, lower cost to rehab, and relatively low rent. They are typically well-located on major thoroughfares and intersections. They can adapt to a wide range of commercial uses, from storefront offices to restaurants to social service agencies to churches. This is the type of real estate for which the market still typically provides a workout.

The fourth type, the unsold lot in the suburban development, will require construction of a new home to be worth what a developer put into it. Until then it will require some upkeep…which costs money.

Real estate is “perishable” in the same sense as food. It can “rot” past the point of no return, it can lose its utility value, and it can lose its monetary value just the same as rotting food. Like less-perishable foodstocks (grain), it can be “warehoused” until the market comes back. And like some subsidized food (excess milk and cheese), it can be given away to low-moderate income people just to get it off the books.

“I assert that much of the economic crisis we’re seeing today is simply the end result of decades of bad decisions driven by bad economic, transportation, housing, and land-use policy.

A mercifully short history of sprawl

To understand the sudden suburban migration of the post-WWII period, and what it means for us today, some historical perspective is required. Happily, I’ve done my best to keep it short.

Powerful enablers are required for such a sweeping thing to happen. Post-WWII suburbanization was caused not simply by the availability of the automobile, or postwar housing demand, but by a converging set of public policies that resulted in blighted cities, towns, and villages, as well as an uglified, overdeveloped countryside.”

—

This hardly qualifies as a focus on the last 20 years; it presents the last 20 years of sprawl as an inevitable culmination of misguided policy. I don’t think the weight falls as heavily on policy as the author seems to suggest.

The repeated choices of most folks in the last 20 years to live in the suburbs instead of fixing up the city means that suburbanization and “owning a piece of the American Dream” are not “myths” but facts. In the preceding posts, I’ve presented some of the microeconomic arguments that mitigate in favor of continued new development: it’s the cheapest way forward in many cases.

My argument boils down to this: housing/development policy didn’t create the mess, and housing/development policy won’t fix it. There are real and serious economic fundamentals at work.

The biggest is this: A massive number of people will have to change their preference and their choices.

The finance, real estate and energy markets are now signaling that more-dense living might be a good choice economically for many folks.

The cost of energy, prevalence of online retailing, lack of growth in retail sales generally and changes in housing finance may finally force financiers to reconsider unabated “suburban with new retail” (i.e. sprawl) development patterns.

So the seeds are present. But changing the American psyche takes a generation, at least.

Chuck I actually agree with most of your assessment, I was just commenting on the mindset and phsycology of the group post WW2 that really kicked off the sprawl in earnest.

Since 1993 however, I have one question concerning the square footage calculation: The trend in mass retailing architecturally was towards stores that doubled as warehouses, or warehouses where one could shop, think Best Buy or Walmart. Could the marriage of warehouse and store skew the American numbers higher? Theres no doubt we are built out, but I cant imagine we are so overbuilt that we have 800% more retail per person than Western Europe.

Marko: The numbers are certainly shocking, which led me to the same question. The typical suburban big-box store is a combination of warehouse and retail, and this presents an obvious issue when trying to compare the U.S. with retail in other countries. I’ve not yet found a study who’s methodology attempts to parse the big-box into its warehouse and retail components. I’d assume that any intelligent study would at least try to do so.

However, an interesting comparison is Canada, which has a remarkably similar development pattern to the United States. By most accounts, Canada today has 13-15 square feet of retail per person, one-half to one-third that of the U.S., depending on what study you believe.

Also, it should be noted that every square-foot of big-box retail in the U.S. requires 3-4 additional square feet of parking, plus an extensive network of arterial roads and expressways, so the land area consumed by suburban retail is considerable.

Indeed, if the U.S. had not opted so strongly for an automobile-oriented development pattern starting in the 1950s, the economic conditions supporting the unchecked suburban big-box arms-race would not exist. Sure, we’d have the occasional mega-subdivision or big-box store, but we’d have a lot less suburbia as we know it.

Perhaps it’s more accurate to say that it’s not sprawl itself that’s the problem, but the overwhelming scale of it.

@ Chuck:

Real estate does go bad, but the difference is that when crops go bad, the producer loses money. When cities go bad, the whole entire society loses. There’s much more colateral damage, and it lasts much longer and is much more expensive to remedy.

I believe that suburbanization would have happened to a degree without the government, but not to the degree it has. There is a strong ethos, probably rooted in our ancestral drive to live in small villages, that pushes many people out of cities. I am an urban booster, but believe that sprawl is not all bad to a degree.

However, this is the one thing that jumped out at me:

“Think about that. At least as much land has been developed in this country in the last 15 years as in the previous 400 years of our history.”

WOW. Thete’s not much arguing against that. Whether you like “sprawl” or not, the fact is that we built too much, regardless of the form it took.

One of the saddest developments Ive witnessed is the sprawl thats occurred in Northern Illinois outside Chicago. 10 years ago it seemed the back to the city movement and rehabilitation of inner ring suburbs was in full gear and the scales had tipped towards density settlement patterns. Myself was working on transit dense townhome developments in the suburbs along rail lines. I dont know how it went unnoticed but it appears the entire Will County farmland was turned over and that the last decade may have indeed been the most brutal, extreme sprawl this region has ever seen, sucking many Latino and Eastern European families right out of the city neighborhoods for the tract homes. The press likes to talk about Chicago’s black population decline but look at Mexican neighborhoods, some had drops of 40%. This financial collapse may finally be the real tipping point towards transit oriented and density standards we should have been following all along. Most of the suburban homebuilders are out of business, the homeowners underwater with their vinyl siding peeling off and the state is finally waking up to the fact that short term gain in property taxes and sales taxes do little to offset future infrastructure upkeep.

When will city planners begin to recognize their own contributions to sprawl? The zoning system is just one gigantic mistake. It might have been an easy way to deal with the problem of public health externalities in the middle of the industrial revolution, but it is a terrible legacy that is not only no longer needed, but contributing massively to sprawl.

Think about it…subsidized loans do damage but there is nothing more sprawl inducing than prohibiting construction in the city. If they can’t build in the city, where are they supposed to go?

Oh, and rent control. But I’m not even gonna start with that one.

Chris and George, the reason why I said that real estate doesn’t go bad is because a property is composed of two important parts: land and the built environment on it.

All land, except in some extreme circumstances, has some intrinsic value. It will have a bounty of natural resources (fertile soil, water, minerals, etc.) or it will have a locational value. Even land left alone has value; either potential value when activated or a catalyst for nearby urbanized land (ask any resident of the Bay Area).

Then you have what’s above the land. Even here, it’s hard to quantify when a building goes bad, and to what degree.

Buildings exhibit entropy, but there’s a big difference between outmoded and uninhabitable. Many buildings fall into this category where they are declining and decaying assets but still functional.

This is why it’s hard to say that a building goes bad.

Consider the well-established economic phenomenon of filtering. After one or two generations, a formerly new building is showing its age and a neighborhood begins to turn over. The building that attracted middle-class or higher residents now turns into a low-income neighborhood.

Is the filtering down of a neighborhood a symptom of breakdown or the evolution of a city? On the one hand, a poorer population takes over lower-quality housing stock. On the other, the filtering represents upward mobility for the new residents who may be leaving even worse housing.

This is one reason why you can’t put an expiration date on a dwelling the way you can on, say, milk or eggs.

Another reason is that age can have a value. A building tied to a famous architect, or a favored architectural fashion, will command a premium beyond its utility. It will also create economic benefits by bearing fruit of a preservation-based knowledge tree.

You may even have neighborhoods — in some extreme cases, whole cities such as San Francisco, Santa Barbara or Santa Fe — where buildings can’t go bad because there’s a local architectural religion. These tend to be fabulously wealthy areas to begin with, and what is a matter of architectural taste in a less well-off community is a matter of shalts and shalt-nots when it comes to private property.

Danny says:

“When will city planners begin to recognize their own contributions to sprawl? The zoning system is just one gigantic mistake. It might have been an easy way to deal with the problem of public health externalities in the middle of the industrial revolution, but it is a terrible legacy that is not only no longer needed, but contributing massively to sprawl.”

This could stand some further elucidation, as I’m confident most would not see this is as anything remotely obvious.

A visceral response I could make is that cities would be very unlivable on many levels without zoning. But I won’t defend this until you defend your position.

Chris Barnett says:

“There are several ways to deal with the 100-year old decrepit house. Demolition is cheapest.”

In all cases? How is ‘decrepit’ defined?

“Also, during the war, hundreds of thousands of southern blacks had migrated to northern cities hungry for defense labor, adding a racial component to the issue.”

The migration happened during the first World War and the 1920s in addition to the WWII which is the reason for little public or private investment in the 1920s to 1940s inner cities. And always intentional redlining was based on race not density. Although you could argue that density followed race. But this article completely sugarcoats the racial component of suburbanization that began with racial covenants in the 1920s and continued through home owner associations in the 1960s to the security cameras and criminalization of urban spaces in conjunction with the mass incarceration of black youth that we see today. To blame white flight and suburbanization purely on policy decisions and economics at the expense of the historical social and racial attitudes is revisionist and patently wrong.

Steve,

Zoning is something that happened in response to poor living conditions caused by dirty industrial pollution intermixing with residential areas. There were no effective means to measure and regulate that pollution, zoning was used fairly effectively to improve public health.

Now the zoning system is no longer needed for that purpose, and the common arguments for keeping the system often revolve around imaginary scenarios that take elementary school level understandings of economics to be able to believe in. The experience of several cities that have either never instituted zoning regulations or have abandoned them disprove the notion that they become unlivable without them.

I won’t bother elaborating any empirical evidence. You can find some of that at this link:

http://www.law.fsu.edu/journals/landuse/Vol101/karkkain.html

I will give you a personal example. In 2004 I was in the middle of a location search for a suitable building to convert into an indoor soccer facility. I had the demand (almost eighty teams with their first 6 weeks prepaid), and it was a sure proposition as soon as the facility was ready. I found an amazing older building that was in an incredible location exactly 1 block between the two busiest bus stops in the city. I had the money to lease it, I had the money to renovate it, but I couldn’t get it to work with the zoning laws. The city planners wouldn’t budge on rezoning the building either, because part of their master plan was to turn that entire block into upscale retail. With all of the other suitable locations within the city either out of our price range or under similar siege by city planners, we moved into a suburban industrial park 15 minutes out of the city center. We lost about 15% of our demand because many of our customers didn’t have cars or had parents that refused to drive them.

Even before the real estate crash and recession, every single business on that street had left. The owner of the building we wanted to lease out had seven perfectly legitemate offers to occupy the building that fell through because of the city planners’ refusal to rezone the block. City planners were still waiting for upscale retail to move in. Today, the entire block is empty and boarded up. But don’t worry, the suburban business park is doing just fine.

Steve,

The city planners are neither planners, nor urban experts. They are hired mouthpieces to give an air of legitimacy to city council members’ visions, which oft include the middle class dreamscapes of latte sipping cafes nestled between bebe and prada shops. I have worked with planners, traffic consultants and commercial property development consultants and my final conclusion is they are paid to say whatever it is they where asked to say, much like an attorney has to defend you no matter your guilt or innocence. Your proposal for a downtown soccer facility is exactly the type of use that makes central cities dynamic, engaging, exciting and unpredictable. And unpredictable may be that mysterious quality that makes successful cities so much fun to inhabit. Now that everyone is an expert at urban planning, it is getting much worse, as you state, we have planned ourselves a few hundred million square feet of empty storefronts with ridiculously high rents.

Rory: Thanks for elaborating on the issue of race, a very important part of the story. But I never stated that sprawl was caused solely by policy decisions or the attendant economics; you should pay more careful attention to my wording.

I did mention racism several times — and quite strongly, I might add. If I happenned to give racism short shrift, I apologize. But this was intentional. The story of sprawl, as it is always told, focuses almost solely on the racial component. This widely-accepted view is simplistic, inaccurate, and perhaps even more revisionist than claiming that race played no part. Which, of course, I never stated.

My intent was to illuminate all of the reasons for sprawl, especially the large enablers. Yes, intense racism did exist well before the 1950s. Yes, it certainly played a critical part in American history and culture. But prior to WWII, the automobile had also been around for a while. For that matter, so was the suburban development pattern. However, without the big policy shifts after WWII, sprawl as we know it wouldn’t have happened.

One more note about pre-WWII black migration: this was a peripheral phenomenon prior to the mid-1930s. Before WWII, there were African-American neighborhoods in most northern cities, and though often vibrant, these enclaves were still rather small.

Steve Magruder, a “decrepit” 100-year-old house is one with several of the following deficits, usually the result of decades of deferred maintenance and neglect:

–serious structural issues, usually related to inadequate or compromised foundation, termite damage, balloon-framing, excessive deck spans, prior “renovations” that removed structural supports;

–a seriously compromised or collapsed roof system and attendant internal water damage;

–seriously deteriorated masonry or wood siding and the sheathing behind it;

–obsolete mechanicals such as knob-and-tube wiring, galvanized iron water pipe, broken clay-tile sewer lateral, boiler or inefficient gravity-heat system;

–single-pane windows, no vapor barriers, no exterior wall insulation, no attic insulation.

–location in a neighborhood with a significant number of houses in similar condition and a median sale price considerably below the cost (even with HOME or NSP subsidy) to remedy the significant deficits.

A decrepit house is usually also vacant or abandoned, boarded, and considered a blight by neighbors because of its deteriorated condition.

Also, forgot to add: demolition usually costs $10-15,000 in my market, far below the cost of a building-code-compliant rehab.

I would propose to move this discussion to the “Greenfield Economics” post, as it’s more related to that post.

@ WAD, I somewhat disagree. Land can have no economic value in today’s market.

Take Detroit. There’s so much land there that would cost money to do anything with, but is worth nothing. You can’t even grow crops on much of it without putting money in it first, because of pollution, or debris, etc. There are examples all over the nation of sites that can receive any amount of investment and just won’t ever produce a profit.

Why? We overbuilt. There’s an aggregate value of all real estate in an area. This aggregate value doesn’t distribute evenly. It concentrates in certain areas, and especially tends to when there is an excess in supply (Real estate is very different from most products in this manner). So in a given area, there is always value to some real estate somewhere for some purpose. But for a specific site, not so much.

Chuck’s arguments strike me as correct, but where can I get some numbers to back up them up, especially about the actual cost of infrastructure in sprawling suburban areas? Has anyone studied this and published some figures?