Crain’s Chicago Business ran a major story assessing the Daley administration’s track record in Chicago last week. The title, “Mayor Daley runs up big debts building his global city; what about the rest of Chicago?,” implies a negative piece, but it has a lot of positive things to say too. The piece includes a quote from a previous major post of mine on the city, talking about how I want Chicago to be less of a generic world city, and find more of its own niche in the world.

I want to expand on that notion today. Some of these thoughts are the beginnings of a major project I have in mind called “The State of Chicago.”

A friend of mine emailed me after seeing the piece and suggested that most of the negatives identified by Crain’s were not unique to Chicago, but were true of almost any global city, thus Daley really can’t be blamed for them. Richard Longworth takes up the theme, agreeing with this, but seeing it in a less sanguine light, asking, “Can Global Cities Work?”

I agree with this. The guy at the top always, fairly or unfairly, gets the credit or the blame for what happens on his watch. In a sense, the principal role of the executive is simply to be accountable. But if the President of the United States can’t control the economy, why would we believe the mayor of a city can? As I argued in my previous piece, Chicago’s transformation is principally the result of macroeconomic forces and structural changes in the global economy. The fact that its transformation is far from unique and is broadly shared by most global similar global cities argues as much. Like the collapse of the Rust Belt before it, the rise of global Chicago and its attendant downsides is part of a macro-phenomenon. In that light, Daley shouldn’t get as much blame as he’s frequently assigned, but likewise less of the credit.

In assessing Chicago, there are two main distinctions we need to make. The first is the entity we are looking at. In assessing the mayor’s job, Crain’s looked mostly at the city, as that is what is under the mayor’s nominal control. But the real Chicago is a regional, metropolitan economy, as Brookings and others have pointed out. To really evaluate Chicago, the best way to look at it is as a region. Of course, the city is a major part of that and a healthy core is part of how you grade most regions, but fundamentally looking just at the city (or the greater Loop) isn’t enough.

Second, cities fundamentally ought to be measured not just against their own past, but against peers as well. This is just like how a fund manager should have his performance judged not only on an absolute basis, but versus a market benchmark like the S&P 500. You can appear to be doing well while falling behind on a relative basis. So to really judge Chicago, you should compare it against other tier one global cities. My comp list is New York, Boston, San Francisco, Los Angeles, and Washington, DC, the last of which I’ll admit is somewhat debatable.

There are a huge number of broad similarities between those cities in terms of their transformations, but I’d like to focus today on one area where Chicago is very different, one that illustrates what I mean by a niche.

At GE, Jack Welch famously only wanted to be in a business if he could be #1 or #2. He recognized that when you are the top player, you can reap enormous competitive advantage and extract the greatest value. This plays into Michael Porter’s cluster theory. Places that establish themselves as the top location for an industry cluster are able to create what Warren Buffett calls a “wide moat” business, one that is hard to unseat and which can again extract higher returns.

To that end, I’ve suggested that cities should not try to become the next hub of generic super-sectors like high tech, life sciences, or green tech that are being targeted by everybody. Rather look for more focused segments within these areas where you can carve out a dominant position, or find other industry specialties to own. This is the “microcluster” concept of which I’ve given many examples, such as motorsports in Indianapolis.

How does Chicago stack up here? Ok, I think. I haven’t done the full research, but others have suggested it has dominated some specialties. The futures exchanges are an obvious example. Saskia Sassen noted that despite the fact that most global cities have many jobs in financial and producer services, they aren’t necessarily directly competitive. Rather, they specialize in different things. Chicago specializes in these services for industries and areas related to its argo-industrial heritage. As she put it, “A steel factory, a mining firm, or a machine manufacturer that wants to go global will go to São Paulo, Shanghai or Chicago for its legal, accounting, financial, insurance, economic forecasting, and other such specialised services. It will not go to New York or London for this highly particular servicing.”

For a city the size of Columbus, Ohio, a collection of microclusters and niches might work. But what about a region of nearly 10 million people like Chicago? The jobs losses in the last decade suggest not. Chicago may have a lock on steel globalization, but how many jobs do this and other similar niches require? The city’s own Central Area Action Plan has a base case scenario of job growth of 3,500 per year, a drop in the bucket for a region with four million jobs. Between 3Q08 and 3Q09 alone, Chicago lost 270,000 jobs. Just that one year loss would take 75 years to recoup at the plan’s growth rate. And the plan says that to hit the number, the central area needs to grow its regional market share.

This gets to the heart of one major difference between Chicago and these other cities. They all have niches. But those peer cities are also the home of one or more of those key 21st century macroindustry super-sectors I mentioned earlier. The reason I advise against trying to compete in those in a generic way is that there are already entrenched competitors, and those competitors are often other tier one global cities.

Consider the following list. It isn’t based on quantitative analysis, but I think foots to conventional wisdom:

CityMacroindustry or EquivalentAtlantaAfrican American CenterBay AreaHigh Technology, BiotechBostonElite Education, #2 Tech HubDetroitAutomobilesHoustonEnergyLos AngelesEntertainment, ArtMiamiLatin American TradeNew YorkFinance, Media, Fashion, Advertising, Art and CultureSan DiegoBiotechWashingtonGovernment

One important difference between Chicago and other US global cities is that Chicago is not the epicenter of any important 21st century macro-industry. This makes Chicago in the global age very different from Chicago in the industrial one.

Some might say, “So what?” and in fact tout this as an advantage. Chicago is one of the most diverse economies in the country, and diversity is often viewed as good. Plus, the fate of Detroit suggests that being a one trick pony isn’t always a good thing. So let’s look at some implications of this.

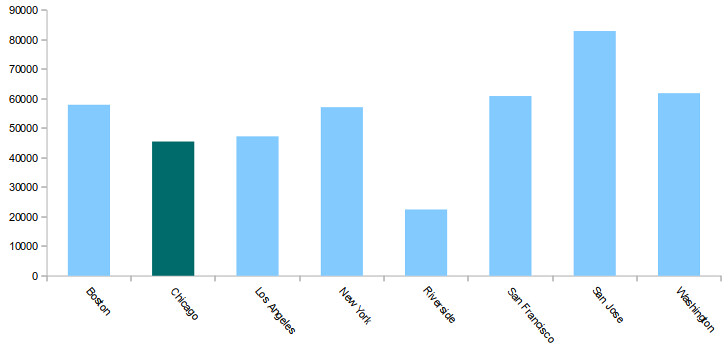

One implication might be that Chicago, since it isn’t the wide moat center of one of these industries, creates and extracts less value than its tier one piers. So let’s see if that’s true. The basic measure of economic activity is gross domestic product. The federal government reports this on a metro area basis, with the most recent release being 2008. Here is how those cities stack up on a real, per capita basis:

Metro Area Real GDP Per Capita in 2008 (in 2001 chained dollars)

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis

As you can see, Chicago’s economic output per person is lower than any of these except the aforementioned Riverside area. In fact, it’s materially lower, except compared to Los Angeles. Even the SF metro, which doesn’t include Silicon Valley, is much higher. Chicago is simply generating less economic output per person than these other places. Now the metro GDP numbers are relatively new, and some people don’t like the data, but this is a real federal statistic.

Let’s also look at the growth in GDP per capita over time. The maximum data series available is 2001-2008. Here’s a plot of these areas over that time, with 2001 set equal to an index of 100:

Real Per Capita GDP 2001-2008, Index with 2001=100

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis, Urbanophile, LLC analysis

This is one clear example of the consequences of being a diversified business center. Chicago will generate less economic value than other tier one global cities because it doesn’t have that calling card industry it dominates and from which it can extract super-normal returns.

This shouldn’t come as any surprise. There’s an axiom in finance that concentrated positions build wealth, diversified positions preserve it. Chicago’s great boom period, where it became large, wealthy, and important, was the agro-industrial age, and Chicago specialized in that field. Chicago was the epicenter. It was its beating heart. But no more.

Chicago has been transformed by globalization, but it is under-performing in terms of economic output, and probably will indefinitely on its current course.

That’s not to say that the other side is perfect either. Detroit is one example, but perhaps a better one is the San Jose/Silicon Valley area. Their problem is that they are too successful at creating wealth. Four quick stats easily demonstrate. Between 2001 and 2008, San Jose’s: a) real GDP per capita increased by 20.8% b) total real GDP increased by 25.9%, c) real GDP per job increased by 39.6%, BUT d) total employment declined by 9.4%.

San Jose/Silicon Valley is like a gigantic tower that keeps growing higher and higher into the sky while its base shrinks. As we all know, that’s not a stable situation to be in. San Jose is caught in a cycle that is long term unhealthy. It is in progress a modern manifestation of what Jane Jacobs called the “self-destruction of diversity.”

Of course, Chicago is not immune from this just because it isn’t the epicenter of a major super-sector. It exhibits the exact same phenomenon, albeit on a smaller scale. There is actually a certain logic in this. In the Crain’s piece, Tracy Cross says that Chicago fundamentally had no choice but to go upscale and focus on upscale businesses and consumers. I agree that was the logical choice, a point I made in my article that I linked earlier and elsewhere.

But just because it’s logical doesn’t mean it takes you in a long term good direction. I’m reminded of a piece Ryan Avent wrote on disruptive technologies and how that dynamic applies to cities. In it he quotes Clayton Christensen via Tim Berners-Lee talking about how incumbent firms react to disruptive innovations:

Generally, they found it difficult to improve profitability by hacking out cost while steadfastly standing in their mainstream market: The research, development, marketing, and administrative costs they were incurring were critical to remaining competitive in their mainstream business. Moving upmarket toward higher-performance products that promised higher gross margins was usually a more straightforward path to profit improvement. Moving downmarket was anathema to that objective.

There’s an obvious analogies to cities. Avent takes it in a different direction, but you can also see how it applies to global cities. Rather than trying to beat Dallas and such at their own game – a daunting proposition – they go upscale. This works for a while, but generally in industry the incumbents end up totally displaced as their market asymptotically evaporates to nothing as it narrows. The specific example in this case was Digital Equipment Corporation – and we all know where they and pretty much every other microcomputer manufacturer ended up. Only IBM – the New York or London of incumbents – survived.

I won’t pretend I’ve thought through every implication and come up with a preferred course of action for Chicago. But neither has anyone else. My own sense of civic pride wants to see Chicago at the top of the league tables, not the bottom. My gut sense is that it requires not a choice of specialization or diversity, but rather diversity of specializations. Chicago will need to both maintain and enhance its diverse mix of headquarters, general business services, and niche industries, but also complement that with a new 21st century calling card to replace heavy industry. It needs to be a city that is known for something again.

Chicago is clearly in a situation where it both is trailing other tier one global cities in generating economic output, and is to some extent exhibiting the taller but narrower syndrome. Right now, that’s been the outcome by default. I will state again that Chicago has been transformed by outside forces. It is the artifact, not the architect. It’s a passenger, not the driver. It might have a first class ticket in many respects, but that doesn’t mean it’s controlling where it is going.

I think it’s time for Chicago to step up and take a hard a realistic look at itself and its aspirations as a city. It’s time to get out of the back seat, and step up and grab the wheel and try to take charge of its own destiny. But I’m not seeing that happen.

And this is another way Chicago differs from these other global cities. It is in its smug complacency about its transformation and how great it is. Perhaps that’s because it is in a region where so many cities have been all but destroyed, hundreds of miles from next nearest peer, Chicago looks around and feels like it is the big winner. I talk to people in lots of cities, and generally they will admit to quite a few of their shortcomings. I may not see eye to eye with them on everything, but they are at least thinking about what they need to do different. I don’t get that sense in Chicago, outside a handful of areas like reducing corruption and fixing the state’s fiscal situation. The people I talk to in Chicago, often outsiders who don’t have positions that require them to be boosters, are nevertheless almost total cheerleaders for the city. Its challenges and deficiencies are blown off or even celebrated. Like a lot of lakefront types many of them hate Daley – who again is not responsible for where Chicago is today economically – but they sure don’t see many serious problems with Chicago.

Other global cities aren’t taking anything for granted. Andy Grove wrote a famous book called Only the Paranoid Survive. Other cities seem a lot more paranoid than Chicago. Silicon Valley knows it has problems. As a report by their leaders put it, “Silicon Valley has entered a new era of uncertainty, with a set of vulnerabilities that could compromise our long-term prosperity. Our continued ability to import and develop talent, fund innovation, and rely on state government for overall support are seriously in question. We are a region at risk.” Concerned about losing ground to London and other global financial centers, New York City commissioned McKinsey to help it figure out how to retain its leadership position.

But Chicago? Other than Longworth and a handful of others, I’m not seeing anything along these lines. In an every more complex, rapidly changing, globalized, competitive world, not only is Chicago not seeking the answers, it isn’t even asking the big questions.

For an index to my Chicago-related postings, click here.

To download the data behind these charts in Excel format, click here.

There’s a tension here between the macro- and micro, particularly when it comes to job formation. Seems like every city I know talks about “clean” tech, “green” tech and bio tech as sectors they want to be strong in. That’s like saying you are going to be a successful doctor when you grow up, when all the while you need to have at least some people skills, have proficiency in biology, and study hard to get into medical school. The devil is in those traits and hard work. And I don’t see that many place struggling with the details of how to get ready and get started.

Chicago can be and is a strong place, but it’s real strength lies in talented young people it draws and the energy that it gets from combining them with people and businesses that are already there. It won’t grow a new Motorola over night. That kind of old “statism” won’t work and never will. We don’t know what the industries of the future are. We just need to make sure that we can create the kind of place that will draw the people who start and grow them. If Chicago has an advantage, it is having that talent pool of middle- and upper level managers who know how to manage businesses once they get through the start-up phase, but they need to incubate the new companies to get to that mid-growth stage.

The most interesting comments I’ve read lately deal with variations on Richard Florida’s “creative places” and “creative class”. These places aren’t necessary arts and design centers, but they are “creative” in being open to doing new things. I sing the refrain of the West Coast here again, but the reason that Portland, Seattle and Vancouver have at least laid the basis for a new economy of the future is that the people in these places, especially the young people who move to them, question and are open to new ways of doing old things. We’ve had coffee for 500 years now. (Starbucks is simply a new way of delivering it. Baby boomers grew up in Converse All Stars. Nike simply created the next generation of shoes.). Back to Chicago: the genius of the place lies in the energy there, its attraction for young people, the fact that it draws interesting and creative thinkers together in tight circles where they can meet one another and work together. What comes out of that is anybody’s guess, but it is not very likely to be something that the formal institutions think up.

P.S. A little known footnote about it’s political history. Part of its grass roots neighbhood thinking comes from the fact that after the 1970s, the neighborhoods pushed for an got city funding for neighborhood coordinators hired by the neighborhood associations themselves. This was part of the peace settlement that came out of stopping a freeway. The payments from the city gave the neighborhood associations continuity of administration; the independent hiring kept those administrators independent of top-down decisions. The neighborhoods did well. Then, a couple of decades later, the institution of City Hall reabsorbed these people and functions, all under the guise of budgetary constraints. I suspect we have not yet seen the cost of this re-absorption. Imagine what could happen in Chicago if things were really more grass roots. What if Daley took some of all that spending and sent it back to the neighborhoods? He might get a really diversified and vibrant. The problem, politically, is that it takes a lot longer to grow such diversified, organic crops, than to do monoculture crops that are fertilized with conventional chemicals.

P.S.

The P.S. refers to Portland’s history.

P.P.S. I didn’t mean to underplay all the hard work that community development groups and non-profits and even economic development organizations are doing to create incubator centers and fund start-ups, but I do hear a lot of high-level decision makers talking about spending money on “clean tech” and other stereotypical solutions, when the really hard thinking involves tailoring a niche to local assets. It is indeed refreshing when a community identifies what makes it uniquely strong and embraces the long-term traits that distinguish it, even if these are the flashy ones that characterize the “in crowd” (to use a phrase that the Urbanophile used or alluded to several months ago.)

Rod, thanks for the comments. These are the types of discussions and debates Chicago needs to be having.

The comparison is apt between Silicon Valley and Detroit, as both illustrate the downside of an economic sector generating too much wealth. (The problem is that the value extracted can be redeployed anywhere, and the wealth-generating process has become so successful that it can be replicated elsewhere without being bound to the land where the success started).

Silicon Valley is in a far better position than Detroit because it has so many economic hedges. Don’t forget, the Silicon Valley/San Francisco/East Bay divide is only one of political borders, not physical barriers.

Its network of highways and public transit has really flattened the region, making the population highly mobile. Because of this, the mega-region stretches from Santa Rosa to the north, Santa Cruz to the south, and to the east, Sacramento and the northern San Joaquin Valley.

Within this area, you have San Francisco and its importance in FIRE, white-collar commerce and tourism; you have productive industrial and maritime trade in the East Bay; you have a thriving agricultural hinterland all within a two-hour drive; plus you are also attracting a young, aspirational class of artists and students.

All Detroit had was cars, and its city region all had factories. The wealth it generated was used to redeploy wealth and synthesize processes that only had the effect of making Detroit and Detroiters obsolete.

The biggest modern example of the Detroit danger would be Las Vegas. Sin City is a world capital of gambling-based tourism. However, Las Vegas is as extremely dependent on gaming wealth as Detroit was to automobiles. Las Vegas is likely to suffer the same fate.

Gambling-tourism is increasingly becoming a commodity industry. Las Vegas’ moat is about to run dry because over time, every metropolitan area will come to want the relatively high-wage to relatively low-skill jobs they provide. First it was the Indian reservations. Then it was severely distressed cities (Detroit, New Orleans). Then it was California liberalizing casino gambling.

Gradually, every metropolitan area will have a casino within easy driving distance. Las Vegas casinos will be more than happy to let these areas pick the fruits from its knowledge tree. Eventually, Las Vegas won’t be needed.

Silicon Valley was smarter, but perhaps more luckier. Yet there’s a mind-set that is still very pervasive among the Bay Area as a whole, and its holding the region back.

The Bay Area is trapped in a “double bubble”. The first bubble was the late-1990s tech bubble. The second bubble: the Bay Area has made the late-1990s bubble the reference point to which all economic progress is measured against. The Bay Area has more subdued growth, but because the new wave of tech or biotech has not produced a frenzy like it did a decade ago, it’s seen as a sign of doom — rather than an extreme outlier as opposed to the mean.

Just a point of clarification: is the statistic of 270,000 jobs lost in one year for the city or the metro area?

ed, metro area. It is the most recently released data from the Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages. There are other data sets with more recent info, but I don’t have them handy. But I can’t believe Chicago has gained any jobs since then.

San Jose is a one-good region, just like Detroit. It’s just that its one good is something in high demand right now. The reduced employment over the last decade is just a reflex of the collapse of the tech bubble, and should be taken as yet another indication that over-specialized regions don’t survive too well.

The example of Dallas suggests that even for a large city, “a collection of microclusters and niches might work.” For larger examples, consider Paris and Seoul. Paris may have a global brand name, and has a ton of internationally recognizable companies headquartered in its region, but isn’t number one in any major industry. The same is true for Seoul.

That’s not to say that specialties don’t work. They do, but it’s best if you have several of them. Even Boston has more than one specialty; everything it does is related to the high-tech sector, but it doesn’t just do software, unlike Silicon Valley. If San Jose is like Detroit or Pittsburgh, then Boston is like diverse manufacturing centers, for example Birmingham. Even better would be specializing in multiple industries that aren’t as related to one another – for examples, Tokyo does finance, electronics, some heavy industry, and academics; and Singapore does biotech, port-related activities, heavy industry, and some finance. Tokyo and Singapore don’t do everything; Tokyo is fairly specialized, Singapore even more so. But they specialize across the board.

Poorly written post.

The facts and the analysis in the first half of this post were great, but you fell apart at the end.

Your argument that Chicago has somehow become complacent, has failed to take a “hard realistic look at itself”, and doesn’t have the “paranoia” that it should is so far from the truth that I honestly wonder if you even bother to read the local media.

For the past several years, Chicago’s local media has been nothing BUT critical of the city’s ability to grow new industries, attract talent & businesses, stem manufacturing losses, tackle corruption, and deal appropriately with headquarters losses. Every potential loss (see Sanjay Jha potentially moving Moto’s handset unit out of state) is seen (somewhat hyperbolically) as an outright devastating blow for the region, while positive news is usually given much less press.

Insofar as I’ve seen, I honestly can say with good confidence that there is not a local media that is harsher on its hometown, more paranoid, and more fearful of every possible bit of potential negative news than Chicago’s.

In addition, I could not disagree more with your argument that Chicago has let macroeconomics go on autopilot and has not attempted to seize the reins on its own fate. OHare expansion, CREATE, a tech venture-capital seeding culture that is finally starting to gain momentum, World Business Chicago, Fashion Focus, recently proposed legislation to attract financial trading firms, a recent bill to cut union costs and once again attract/retain conventions at McCormick center are obvious examples stemming from both the private and public centers that come to mind.

Your facts are good, but I couldn’t disagree with your conclusions more. Reality is, Chicago’s paranoia is what has kept that region on its toes and what has prevented it from sinking when it perhaps otherwise should have.

Alon, the interesting thing about Silicon Valley is that “employment” is a very elastic term.

Silicon Valley, much like the entertainment industry in Southern California, created a sector that is both very high-paying and itinerant at the same time.

There’s a very large reserve army of code monkeys who work by the project, then must find a new project or use the idle time to pick up a new computer language. They know this is the nature of the industry and orient their lives around this erratic work schedule. This probably better prepared them for lean times and weaned them from job dependency than the factory workers who had always counted on a career at the plant.

The Silicon Valley cities are more dependent on the largesse of the tech companies than their residents. The larger San Jose and Santa Clara at least have major universities and an airport that provide an economic bedrock should the technology sector decide to pull up stakes. The Sunnyvales and Cupertinos are more dependent on the fortunes of their major tech firms.

The key difference between the cities and the residents are that the residents will go to where the jobs are. County lines and even the bay are not barriers to movement. The Bay megaregion is diversified while at the same time its subregions are highly overspecialized.

Aaron, I am curious as to why Washington D.C. would be debatable as a Tier 1 global city.

Is it because having a preponderance of workers dependent on government paychecks is cheating, economics-wise? By most other measures, DC has the makings of a global city.

A large private sector exists to service the government. As a strong national capital, it forges ties with every nation in the world. It is surrounded by major educational institutions within DC, Maryland and Virginia. It has a port for some maritime trade, and is a major center of arts and learning.

This would suggest that government is more of an entree than the entire meal. A downsizing or devolution of government functions would hurt Washington less than an area whose largest employer is a military base or whose college graduates can only find public sector work.

Aaron, thanks for the thought provoking post.

What comes to mind is this – has globalism been to Chicago (and the Midwest in general) what Wal Mart has been to small towns?

In Wal Mart’s case, local economies are devastated as the dollars are sucked out and no longer circulate within the community. With globalism, the good paying jobs are lost to countries with early industrial age working conditions.

All of Chicago’s new parks, schools, stadiums and landscaped boulevards can’t attract enough high paying jobs and revenues to compensate for the devastating loss of multiples more off shored middle class jobs.

The Midwest’s greatest handicap to date has been the benign acceptance of the myth that globalism was somehow inevitable.

To create solutions, a consensus must first be reached regarding the source of the problem. I think it would be useful to first calmly step back, take a deep breath and, to paraphrase Elizabeth Warren, follow the money.

Las Vegas has more going for it than gaming–it also dominates the convention trade, especially where large conventions (with hundreds of thousands of attendees) are concerned. Not many places in the US have either the floorspace or the hotel rooms to handle this level of business. And unlike traveling exhibitions like auto shows which book in smaller convention halls ’round the country and attract a mainly local audience, most attendees at Las Vegas conventions are out-of-town guests, staying in the hotels, shopping in the shops, going to the shows, and playing the games.

(Incidentally, Las Vegas is one of the few places in the US where Starbucks routinely charges extra for their coffee–the company imposes a uniform price structure across the vast majority of their stores within a country.)

Thanks Rod, for your first comment.

A great city is about proximity, diversity trade and exchange. For the most part one just can’t guess where exactly that will lead.

I also agree with Alon’s point about diversity and that a place can be pretty sucessful while not being a kingmaker leader in any single industry. In fact it might very well be that these places might be gestating some new thing we can’t recognize as important yet.

My guess is that just being a pretty good, diverse, open and reasonably dense place in America today is often niche enough. I mean it seems to me that the whole mega convention and mega conference business is built on the fact that so few cities really perform well as places to trade and exchange, show off new products and meet lots of people easily.

Funny, I always thought of Chicago as a crossroad. That’s probably because I’ve never lived in the Midwest and for many years the only part of Chicago I had personal experience with was O’Hare. I always wanted to visit (and finally did, a few times), but all that time what Chicago conjured for me was planes, trains, and buildings (because of its renowned architecture). I guess that’s not a whole lot to build an economy around, except with regard the points some have made above, which I think are important. Chicago has an enormous advantage in being the Midwestern capitol. Couple that geographic and infrastructure advantage with being, as John wrote, a “good, diverse, open, and reasonably dense place,” and that seems to situate Chicago really well.

I don’t think Las Vegas is nearly so vulnerable as Wad seems to think. By & large, people don’t go to Las Vegas just to gamble; most people can do that closer to home. But Las Vegas is more than a collection of random casinos, like Disneyland & Disneyworld are more than collections of amusement rides. They are destinations. Chicago, it seems to me, is also still a destination, even if it wasn’t self-consciously crafted as such the way Vegas and the Disney properties were.

I also think there is a giant elephant in the room that needs to be addressed.

Look at Table I of this post.

Look at every city’s “specialty”, and now look at New York’s. New York pretty much hogs everything, doesn’t it? As long as American remains a place where New York remains top dog in a half a dozen industries, that doesn’t leave a lot of room for other places, does it?

Even worse, the industries where Chicago in particular is trying to excel are the ones listed next to New york. Chicago truly is in New York’s shadow, in every frustrating sense of the way. Breaking out of that shadow has been Chicago’s challenge since its inception.

I agree with Michael M. Chicago was an agri-industrial powerhouse, but that era has largely gone. It’s raison d’etre is largely one of being THE city of the heartland. Every other city Chicago is compared against is on the coasts. A country as large and wealthy as the U.S. simply needs a city in the middle. Chicago has over time aggregated that position to itself. It continues to draw talent largely from the heartland. I once had a conversation with an engineer from a smaller Midwestern city who wondered why his hometown was a laggard. I asked him to ask himself why he was in Chicago and not in his home town. Chicago’s position as a global city is largely as result from its being the capital of an important part of the globe.

Joel, I agree with that to a great extent. I think Chicago is much more regional capital than global city. Perhaps a better comp is Atlanta in that case. Being the capital of a laggard region would be another possible explanation of Chicago’s relative underperformance.

This article examines some of that:

http://midwest.chicagofedblogs.org/archives/2010/02/questioning_chi.html

I think this trade, regional capital function just is underated. It’s really, really important. As people have said, to be capital of a an underperforming region is something hard to evade.

But also, the midwest and America in general are probably suffering a lot because it lacks a lot of cities that really perform that function well so there’s some kind of feedback loop.

Chicago, on it’s face also has a tremendous natural niche it should be able to fill, which is as a “cheaper version of NY”.

In the crowd I travel in of lower earning people, Chicago is often picked as a cheaper alternative to NY. Lots of people are looking for that but it looks like government there has loaded on costs and undermined the kind of broader neighborhood development that would play on that.

Chicagoland’s “microindustries” (an odd term to use, since many of these industries generate billions — why not simply “industries”?) would include:

– Pharmaceuticals/biotech/medical devices (Abbott, Baxter, Takeda, dozens of smaller firms)

– Consumer Foods (McDonald’s, Sara Lee, Kraft, etc.)

– Transportation (Boeing, United Airlines, countless trucking and rail freight companies)

We could probably go on, but that seems like enough.

I find it odd that you’re trying to judge whether Chicago measures up as a global city/region, but then compare it to non-cities such as the Inland Empire, which despite having a large population is anchored by two remarkably un-global cities (ranked 61st and 99th most populous in the US). Likewise, I don’t believe anyone considers San Jose a global city. Instead of weighting your comparisons heavily toward California, you could have included the other top US cities on the GaWC rankings, Atlanta and Dallas. Heck, throw Miami in, too.

PS: Boston appears to be listed twice on the Real Per Capita GDP chart.

“In the crowd I travel in of lower earning people, Chicago is often picked as a cheaper alternative to NY. Lots of people are looking for that but it looks like government there has loaded on costs and undermined the kind of broader neighborhood development that would play on that.”

This is why I moved to Chicago. I don’t think people really want to think of the city that way, as a second-rate version of another place, but there’s not anything wrong with it if you can set aside boosterism and the cult of “excellence” embodied by that Jack Welch bit. As New York becomes more expensive Chicago becomes more attractive for people who want to live in a large, dense city and who are not wealthy. In the United States, there are really very few options for such people.

Was expecting to see something on the CME, which is experiencing record trading volumes. Why do you think CNBC always cuts to Rick Santelli?

The Chicago Merc isn’t just the country’s leading exchange for futures and options, it’s the world’s. Going back to the CBOT, Chicago’s always been a leader in financial innovation.

To the commenter who mentioned something about tech & venture capital, you’ve got to be kidding me. VC is losing its market share in new business finance, and is a Silicon Valley funding mechanism, and always will be.

I wish everyone in economic development would just go a day without saying “tech”, or “cool”. Chicago certainly needs neither to thrive.

The Merc was a pretty early adapter of tech, wasn’t it? Even so, the futures/options markets now so swamp the stock market in importance.

Even so, I think the real story of Chicago is much like Pittsburgh’s taking into account the assets there,the relative performance is not so great.

This mythology of the poor me industrial city left with nothing and revived by politicians is very self serving. Chicago was left all the assets and importance as a central regional center.

Same with Pittsburgh and all it’s colleges, museums, corporate headquarters, fine housing stock etc…

It just seems from a distance that people want a medal for just not messing up or destroying more of their cities. I mean anyone might look good if compared to the Cabrini Green Era.

Anyway, I’m not an expert on Chicago.

In a response to another post, I kind of hamhandedly expressed my frustration with Chicago’s lack of preeminence in some economic sector, like other global cities. After reading this, I’ve had to modify that claim. Chicago’s move to the global stage has been because it dominates the social, economic and cultural scene of the middle of the USA. It’s a regional capital that has the appearance of a truly global city because of its mass, and as a resident of the region, I’m becoming more and more OK with that.

I’m hardly the most well-versed person on the financial industry, but the Merc doesn’t seem to have the same impact on Chicago’s economy that Wall Street has on New York’s. Chicago is definitely one of the world leaders in air and rail transportation, but transportation is a systems function that doesn’t spark the imagination like arts and culture or even finance and government. Same with food processing.

Bottom line, I think Chicago accumulated enough wealth, population and infrastructure legacy from its industrial and ag roots to transition to this era relatively easily. Detroit, Cleveland and St. Louis didn’t accumulate enough to make the transition as well as Chicago did. But it might be only because of its size as the third largest region in the world’s largest economy that can allow it to claim global status. I don’t know if Chicago will ever become preeminent in some sector, short of government intervention.

Another thought: Aaron had an interesting post a few months ago about the challenges facing St Louis–most importantly, the fact that the city relied heavily on older companies that had established themselves in the area long ago, yet lacked entrepeneurship.

I think this is a problem that plagues a lot of midwestern cities.

In addition to Andrew and Eli’s posts above, the reason I am less concerned about Chicago is that it has managed to draw a large number of young people seeding new companies. They may not get the kind of attention as those huge Silicon Valley startups turned global giants such as Facebook and Google, but slowly and steadily, successful new companies are being formed and rising through the ranks.

To me, a dedicated generation of creative individuals interested in staying put and creating the companies that will draw wealth into Chicago in the next century is far more important than any other concern.

The kinds of companies being formed and growing in Chicago are inclusive of new generation-type companies as well as traditional manufacturing types. This speaks more to the health of the region than anything else. Every year Crains publishes the “Fastest fifty”, the fifty fastest growing companies in the metropolitan region. This year’s list ranges from services-oriented companies to software & telecom companies, manufacturers, healthcare sector companies, financial insitutions, and a growing nationwide pharmacy. It should be noted that the majority of these companies are located in Chicago city proper–another plus that makes Chicago nearly unique among America’s other “global cities”.

If anyone is interested, I suggest you check it out yourself:

http://www.chicagobusiness.com/cgi-bin/mag/department.pl?id=120&post_date=2010-06-05

I’m not too sure about St. Louis, but neither Cleveland or Detroit had major roots as central trading centers and trade in one form or another still seems to be the key linchpin of a sucessful urban center built to last. They had some importance as shipment hubs for bulk industrial goods and then quickly became very focused manufacturing hubs.Detroit, made almost no lasting investments in it’s future and the few big ones it did make were often mistakes.

Personally, I think that the city and it’s mega unions grew up so closely together strangled the baby in the cradle. It was just assumed these companies could not fail, and distribution of wealth became the main priority. Everything can fail.

Chicago’s history is closer to New York’s in that major league trade, financial dealing, wholesale and retail was woven into it’s fabric. By the way, the NY area certainly did plenty of manufacturing too. It seems that all the big player cities that came up here like, NY, Singapore, London, Hong Kong and Tokyo have roots as very major trading centers.

Chicago’s killer ap was railroads and I still think that’s the most important thing for the future of the city and the midwest.

I don’t think it’s surprising that these type cities also can end up pretty diverse, since the dealmaking, idea exchange and trading function is at the root of most business activity.

While Chicago is an air and rail hub, this isn’t in itself that big, not yet. The four Class I railroads in the US have about $50 billion in annual revenue among them, and the two airlines with O’Hare hubs have another $40 billion. This compares with $110 billion in annual revenue from HP alone; and Silicon Valley is about much more than just HP.

However, freight rail is a potential growth industry, and here is where Chicago leadership could help. The slowness and unreliability of North American freight rail ensures that it can only carry the lowest-margin, lowest-value goods, for which the only thing that matters is cost per ton-mile, on which trucking can’t even begin to compete. Thus rail has a 37% share of the US freight market by ton-miles, but only a 4% share by value of goods.

Much of the slowness comes from Chicago bottlenecks, which are the worst in the nation. It can take two days for a freight train to navigate the city’s switchyards and grade crossings. If Chicago collaborates with the railroads on relieving those bottlenecks, as LA did in creating the Alameda Corridor, it will be able to give the industry a strong boost, as well as boost its stature within the industry.

No, I’m mare talking about passenger rail.

@ Alon 7:37 — I think you are right about freight rail being a growth industry, and I think you might be implying that Chicago can take leadership in next-generation rail, freight and passenger.

Chicago has taken a big step in relieving the the bottlenecks you mention. The City and railroads will be receiving millions in federal funding from the Department of Transportation’s TIGER Grant to support the CREATE program to smooth out the Chicago rail bottlenecks.

Chicago may become a leader in this regard, but I fail to see how this pushes Chicago closer to true global city status. We could clear the bottlenecks, we could continue to develop the intermodal facilities that shift goods from rails to roads. We could make Chicago the leader in U.S. HSR development. But unless Chicago takes the lead on, say, next-gen HSR (and the U.S. is already behind much of the world on that), I don’t see how this creates enough of a pull to bring more of the “best and brightest” to the region.

Well, both. I don’t know the logistical road blocks but the key great thing about the whole midwest and the rust belt around Chicago was mostly flat land and often pretty short distances between cities.An absolutely perfect railroad landscape. This combined with several killer sectors like agriculture which only seen to become more important and Chicago is just really important.

Obviously rail is also the perfect form of urban transportation. No doubt retrofitting now is a big problem and huge expense.

While the premise of the article that Chicago is at risk due to the diversity of its economy is invalid, it makes a couple of arguments that merit further exploration.

The first argument is that globalization presents a risk in that formerly high value, high-income jobs are being commoditized and moved to low cost regions in the world.

The second argument is that in order for an entity to build competitive advantage, create a wide moat, and build a position where it can extract greatest value, it must focus on areas where it can be #1 or #2 competitor.

It’s hard to argue with these statements, so let’s put some thought into areas where Chicago can be a #1 or #2 competitor due to its existing natural and historical advantages.

Here are three advantages:

* Transportation / Distribution / Travel

Chicago has the #1 / #2 airport in the world, and is the hub for the United States rail and highway systems.

* Education

Chicago has an outstanding university system including Northwestern, University of Chicago, UIC, IIT, Depaul, Loyola, School of the Art Institute of Chicago, and Columbia College.

* Trading / Finance / Business Services

Chicago has top exchanges, including CME/CBOT, Chicago Board Options Exchange, Chicago Stock Exchange, and Chicago Climate Exchange. Chicago also has noteworthy financial services and insurance firms, such as Allstate, Aon, Calamos Investments, Chase Commercial Banking, Citadel Inventment Group, CNA, Discover Financial Services, Morningstar, and Northern Trust.

Given the existing foundation of competitive advantages, what are some complementary pillars of strength worthy of investment? Here are a few:

* Conventions

* Tourism & Entertainment

* Intermodal Distribution

* Import/Export

* Startup company incubation

* Small business and franchise services

* Technology & Telecommunications

* Media and Film

In addition to re-investment in Chicago’s core strengths of transportation, education and finance, investments in these areas will build on existing strengths and will support an ecosystem in which the conditions are right for each of the others to blossom.

The problem is that the skill to build the railroads and the rolling stock is unlikely to come from Chicago.

Alaska has a lot of oil wells that doesn’t make it the center of the energy industry. The people who know about that stuff are centered in Houston.

Chicago grew up as NYC’s entrepot in the middle of the continent, c’est la vie.

Wow – thanks for all the comments while I was away. I really appreciate them – even from those who strongly disagree.

It sounds like there are three basic theories on Chicago: global city, Midwest capital, and less expensive/more-livable mini-NYC. There’s probably some of all three, but in what proportion? And what are the implications of that? For example, if you want to spend like a global city, do you need to earn like a global city?

I will try to come back tomorrow and respond to some specifics.

Alon, I agree that Boston has done well with a diversity of specialties. I sort of consider their core industry elite education, but beyond that they are #2 or #3 in a number of big sectors: high tech, biotech, finance. In diversification vs. specialization, a diversity of specialties is better.

Richard Florida and Glaeser have both said that NYC is not nearly as dependent on finance for its overall economy as you might think, but I haven’t looked at the numbers. I’d suggest in terms of tax revenues and income at least, if not in total employment, it has to be up there.

TUP, I’d agree that there is some criticism. But I think the Crain’s article is a good example. It is what I call a tactical critique. It’s about specifically Daley and what policy changes he would have made. It isn’t about looking at Chicago and asking questions about its role in the world or overall competitiveness as a region. (In fairness, their mission was to look at Daley has a mayor).

Similarly CREATE and the O’Hare Modernization Program are both designed to address obvious bottlenecks. I’m actually a bit of a contrarian on transport as a future industry for Chicago. It will obviously be a dominant air hub and rail hub. For growth that can take direct advantage of that (e.g., intermodal terminals), we’ll see more development. But the extreme congestion in pretty much all freight modes in Chicago makes this a place you’d avoid if you didn’t need go there. Why send a truck through Chicago if you don’t have too? Even CREATE will only increase average train speeds from like 6 MPH to 12 MPH. A big improvement, but this will remain a big bottleneck.

Rather than the transport legacy, I see Chicago’s central location as a key. It is the premier interior business center. And it (along with Dallas) are the best places to be if you need to fly around the country. I’ve got an entire post about this based on my personal experience that needs to be written at some point.

Andrew, I agree the Inland Empire doesn’t fit, but I didn’t want to be accused of lopping off the part of Greater LA that looked bad on these metrics. Hence I left it in.

You are right that Chicago has many industry segments, the question is whether they will sustain the economy going forward and generate the wealth needed to support the amenities the city wants to have. The huge jobs losses and economic underperformance would suggest that’s at least an open question. Chicagoland lost 200,000 jobs in the last decade. Cook County alone has over 225,000 fewer jobs today than it did in 1990.

The clusters you cited are mostly legacy industries that aren’t growing. Chicago is not the pharma capita of America and the traditional pharma business is having macro troubles of its own. Pfizer and Takeda both just did big layoffs and I don’t see those jobs ever coming back. Albeit at low total employment levels, investment is migrating to biotech, which is based in California and Boston primarily.

These legacy industries will shrink or at best grow slowly over time. (The consumer good sector is perhaps a better one as marketing centric industries could do well here).

Eli, your point about Chicago being the cheaper/more livable big city than New York is an interesting one. Visiting New York always makes me think that a) it would be cool to live there b) I’d have to have a lot more money than I do now! I’m not per se a coastal migrant, but appreciate the lower cost of Chicago. Beyond which, Chicago has the added advantage, in its professional districts at least, of having a comfortable Midwest/Big Ten culture and vibe that makes it an easy place for Midwest farm boys like me to move.

I wish Chicago would be more inclined to show the same understanding about other cities who say the same thing lower in the pecking order. When I say nice things about Indianapolis – which would tell you similarly they have a lot of urban amenities at a price/livability level that is tough to beat – many Chicagoans are quick to express their utter disdain for the place, or other smaller Midwest cities. I’ve long argued in response that every argument that says places like Indy can’t make or that you should from Milwaukee to Chicago could nearly identically be made about Chicago vs. New York. But I don’t think there has to be just one winning city in the US.

It sounds like there are three basic theories on Chicago: global city, Midwest capital, and less expensive/more-livable mini-NYC. There’s probably some of all three, but in what proportion? And what are the implications of that? For example, if you want to spend like a global city, do you need to earn like a global city?

I don’t believe this question can be answered without breaking up the Chicago metro area for the purpose of analysis. The core city of Chicago, i.e., the central area and certain surrounding neighborhoods, is in equal parts a global city, Midwest capital and mini-NYC. Walking the streets, one can’t help but be struck by the throngs of people, many from diverse backgrounds, and many from different countries. It’s a similar experience, albeit on a lighter scale, to what one might experience in New York. If that’s not a global city, Midwest capital or mini-New York then, what is?

Regarding the pecking order, Aaron, I’m sorry, but I’ve been to many Midwestern cities–and all cities have their good points–but none can match the experience I just described. So there are no other “global cities” or “mini-NYC’s” in the Midwest, or in much of the rest of the middle of the country for that matter.

The neighborhoods outside this core, and Chicago’s suburbs, are not more unique or attractive than those of any other decent sized Midwestern city. And many areas are just as troubled, if not more so.

So it’s Chicago’s core that sets it apart from any other Midwest or heartland city. And this has implications in turns of attracting talent. But it does not address much of the systemic economic dichotomy afflicting not only Chicago, but arguably the entire Western Hemisphere.

I love it. Just like high school. Once you get in the cool kids club, everybody below you in the pecking order is excluded.

I’d like to see talent defined, and measures of Chicago’s talent attraction vs. other cities. I see many assertions made about talent, but very little quantitative analysis.

I think I was the first one to bring up that point about a cheap version of NYC but of course it’s not exactly an original one. Lot’s of people make that comparision and New Yorkers almost always have a favorable opinion of Chicago.

I know Chicago just isn’t that far along on the transit and urbanism scale, but really this is not small position to have.

There simply are no other really urban New York type cities of scale in America so this is a huge, huge niche.This should be key to thinking in Chicago.

We are in a completely unprecidented time that has left Chicago with a huge opportunity. For the first time, I can remember in New Yorks history, there really is no reasonable significant place for lots of moderate income people to live. Yes one has rent control and that insures that a an entrenched crowd of mostly older people don’t have to leave. But for the young new blood NY has always depended on sucking in life has become harder and harder.

A real attack on New York’s core creative industries could easily be launched by any city of scale, with a decent urban structure that wanted to suck in those people.

The same facts apply to start ups or any higher risk business.

I love it. Just like high school. Once you get in the cool kids club, everybody below you in the pecking order is excluded.

I’d like to address a couple of your points – particularly since I hated high school for the very reason you cited!

First, the energy and crowdedness of Chicago’s downtown is unmatched in mid-America. And the diversity and international crowdedness at that. So on THAT factor it rates as a global, mini-NYC: It FEELS like one. That can, and no doubt does, attract talent.

Does that make Chicago a better metropolitan area on other scales, such as job creation or population growth? Not necessarily.

So it depends on what high school “clique” you’re referring to.

It’s hard to say what new industries will dominate in the future. There are a couple that Chicago might be structurally well-positioned to take advantage of.

Wind and Nuclear: Chicago already gets about half its energy from nukes. And with Exelon and Argonne and Fermi labs in Chicago, it’s possible that the region could take a leadership role if nuclear power takes off again.

New agribusiness. Chicago is a key player in chemicals and products derived from cheap corn and soy: Archer Daniels Midland, Corn Products International, etc. If fuels and plastic from botanical factories are competitive with oil-based fuels sometime in the next generation, Chicago and the Midwest are well positioned to take advantage. The bread basket would be newly relevant.

Manufacturing automation. If automation technology advances at its current pace, it will only be a couple decades before it’s more efficient to use next-gen automation in the U.S. than even to employ subsistence laborers in Asia. The region’s infrastructure and manufacturing legacy would make it well positioned to take advantage of that trend, if it develops.

Likewise, the area around Chicago has lots of fresh water and wind-energy potential. If there are energy disruptions in the future related to fossil fuels, or if there are legacy stresses on fresh water supplies in the West, Chicago should be attractively buffered.

Chicago does lead in a few non-trivial specialty industries right now: Transportation logistics, the aforementioned commodities and derivatives businesses, Agribusiness, internet services and data center management. Three of the largest data centers in the world are in Chicago and Chicago has, perhaps, the best internet infrastructure in the world; if bandwidth availability and stability becomes even more key than it is now, Chicago is well positioned. You can’t rest your regional economy on table with only those legs, but you never know what small advantages might end of being key foundations in the future.

I think there’s a fourth theory of Chiago – namely, Chicago as a national city. For example, in air traffic, it’s clearly not just a regional capital, but it’s not global, either. O’Hare’s international traffic is barely higher than Newark’s and barely more than half of JFK’s. The Chicago airspace is more important as a national hub than as a global hub.

Commentary from Jim Russell:

http://burghdiaspora.blogspot.com/2010/06/chicago-talent.html

Interesting point, Alon, but wouldn’t being a National City in the world’s largest economy make you a global city? I’m guessing there are more international flights into Karachi, Mexico City or Istanbul than Chicago, but that doesn’t make them more “global.” New York, London and Tokyo are simply in a class by themselves. If Chicago doesn’t compare to cities like those favorably in every metric, it doesn’t necessarily mean anything diminishing.

If Aaron’s point is that once you say “we’re just a smaller, cheaper X” then you can slide it pretty far down, cause another place can say” we’re an even smaller, cheaper X” then he’s onto something. What’s the cut off? Probably it’s just the place where you happen to live.

Anyway are other midwestern cities the benchmarks Chicago is going to look at to measure national or international prominence?

“We’re not Detroit!”

To be honest, I think a lot of people around here, many being native midwesterners from cities other than Chicago, are using a really bad recession as an opportunity to pick apart Chicago’s weaknesses.

No offense, but Aaron you yourself were very bullish and Chicago and its prospects only 2 years ago. I get the same vibe from this Jim Russell guy that you quoted

I hate to post multiple times, but I’d also like to add that even Bill Testa at the Chicago Fed, whose knowledge on this subject and blog I immensely admire, wrote two different blogs:

1. Chicago–Tall and Striving

this one had an optimistic outlook on Chicago’s economy

2. Groundhog day for Chicago’s economy?

this one had a pessimistic outlook on Chicago’s economy

These two posts by Mr. Testa were written just 3 months apart. Don’t believe me? Check it out yourself, whoever is interested.

Let’s put to rest the idea that Chicago is something other than a global city.

Nearly every listing of global cities includes Chicago. See this Wikipedia article for four listings in which Chicago is near the top of the list of global cities:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Global_city

Chicago has the fourth largest Gross Metropolitan Product of any city in the world per PricewaterhouseCoopers:

https://www.ukmediacentre.pwc.com/Content/Detail.asp?ReleaseID=3421&NewsAreaID=2

Also note that Chicago is listed as one of the top 5 centers of commerce in the world:

http://www.mastercard.com/us/company/en/insights/studies/2008/wcoc/index.html

Eric, you’re kind of right: being a national city in a large country does give you global influence. However, you’re still tethered to national fortunes.

Chicago does, in fact, have less international traffic than Istanbul (but more than Mexico City and Karachi). This is because Istanbul is an international hub and Chicago a national hub, and because the US has a much larger internal market than Turkey. That’s why I’m not comparing US airports to non-US airports.

By the way, the reason I talked about freight rail earlier in the thread and not passenger rail is that public transportation is not exportable. It works wonderfully in improving access and mobility, reducing people’s transportation costs, and improving public health, but those play support roles to the main, exportable industries. Even cities with trendsetting expertise in public transportation operation and construction – Calgary, Madrid, Barcelona, Zurich, Tokyo – have not been able to export their knowledge in the form of international consultancies.

Freight rail and air are different, because there’s a hub status there, which is sort-of exportable, in the sense that it moves money from outsiders into your region.

As I’ve written before in comments to this blog, the discussion at hand can take on very different implications based on the time frame we’re adopting. Chicago is a very new city, even by U.S. standards, if we’re including NYC and Boston. By world standards, it’s a very, very young city. How many macro business cycles has Chicago actually been through, compared to, say, London?

If we base trends (and action plans) based on arcs of a decade or so, we tend to get very different answers than we do if we analyze in terms of 50-year or century patterns.

I say this to remind everyone about all the dire and virtually useless thing people were prognosticating about Chicago and cities in general as little as 30 years ago — the late 70s and early 80s — a blink ago, for those of us who were entering our professional careers as planners back then. People were still grappling with women entering the workforce, for chrissake. No one had heard of the internet. An African American in the White House? Yeah, when cars fly. The Berlin Wall was ten years away from being torn down; China was on almost no one’s radar. People were taking note of a small but promising “back to the city” movement. NYC lost ONE MILLION people in the 70s and nearly went bankrupt. Everyone figured it was a goner. And probably a third of the readers of this blog weren’t born or hadn’t graduated from kindergarten yet.

If we take a slightly longer [and less alarmist] time frame, say, another 30-50 years, what stands out are not mini-trends but the biggies, like climate change, demographics, water, the ascendancy of China and Asian economies, changes in energy production and consumption as we are forced off oil … These things are going to happen no matter what civic leaders do between now and then. And these are the factors that are going to determine the fate of Chicago and all other cities.

I love the micro-analysis on this blog. But I’d love to see some more longer-range perspective — both looking back and looking forward — in trending out what’s next and what can be done to capitalize on it.

Thanks, Aaron, for another provocative post!

Iron

Chicago’s a railroad center.

It seems to have forgotten this and failed to invest in that much, and railroads have moved their HQs elsewhere.

Did BNSF really move from Chicago and Saint Paul to Fort Worth because of Chicago’s rail bottlenecks?

I think maybe the GDP should be normalized by some kind of cost of living measure. My impression is that someone in Chicago may get paid less for doing the same job as someone in one of the coastal Tier 1 cities simply because people need more money for housing in places like LA, SF, and NYC. I think Chicago’s economic output per capita may be fine, but we’re just not getting paid as much for it in dollars. Does that really matter though if we don’t need as many dollars for the same quality of life?

John, I’d probably normalize income to cost of living, but not economic output. Though some have argued they are related. That is, more productive workers are the only ones who can afford to pay the high prices of expensive areas. Also, areas get expensive because of the high value workers they have (assuming outputs eventually translates into income), and the area is valuable precisely because it contains so many high value workers.